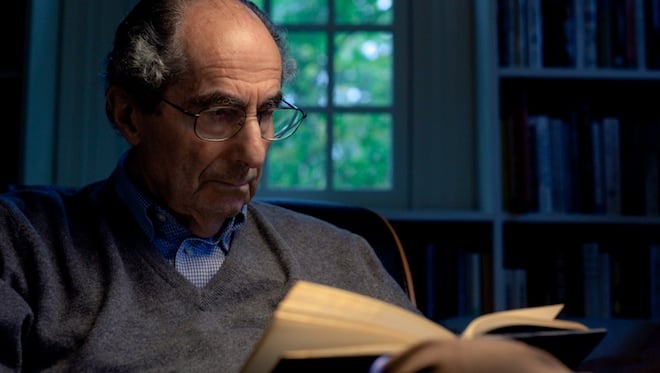

‘The struggle with writing is over’: Philip Roth at 80

America’s greatest hope for winning the Nobel Prize for literature has never been more relevant

Share

It’s hard to imagine Philip Roth, the now-retired American novelist, browsing the aisles of Lee Valley looking for a woodworking project to pass the time. Try picturing him at an RV dealership, contemplating a long-distance road trip. Envision him on a golf green, working on his long putt. On its “How to Stay Busy During Retirement” entry, wikihow.com recommends restless retirees write an autobiography, advice that would surely give Roth a chuckle.

On the occasion of Roth’s 80th birthday, PBS’s American Masters will air the 90-minute documentary, Philip Roth: Unmasked. While the film offers no clear answers to the question of What will he do now?, it does provide an intimate look at the life and work–over 30 books in a career spanning over 50 years–of one of America’s most enduring voices.

Because Roth has so relentlessly pursued himself as a subject, fans of the author might not be surprised by the documentary. Roth states outright at the opening of the film that he has two great calamities awaiting him: death and a biography. “Let’s hope the first comes first,” he says.

Roth has always verged toward the post-modern in his work (think of a character called Philip Roth tracking down his doppelganger in Israel in the novel Operation Shylock), but since retiring he has gone positively meta. In September of 2012 Roth published an open letter to the editors of Wikipedia on The New Yorkers’ website. He had tried, without luck, to correct a spurious entry about the motivation for one of his 2000 novel The Human Stain only to be rebuffed because he lacked a credible secondary source. Then came the news of his retirement from writing, which was quietly published in an interview, in French, in Les Inrockuptibles. But could the grand sage withdraw to the mountain for a life of quiet contemplation? One morning in a New York deli, he told a young writer-waiter that the writing life just wasn’t worth it, that he should quit while he was ahead. This sparked a mild online controversy that found Roth rebuffed by Elizabeth Gilbert, who took umbrage with Roth’s depiction of the writing life as ‘hell’ (we can’t all eat, love and pray). He once again did not win the Nobel Prize for Literature, despite the fact that 7.7 in 10 people think he is America’s Greatest Writer.

If all this sounds like something from the world of Nathan Zuckerman, Roth’s most conspicuous alter-ego, take note that Roth has a Post-It note stuck to his computer that reads: “the struggle with writing is over.” For once, these strange, adumbrating occurrences will remain off the page, unfictionalized.

So what is Roth, a man who claims to have written nine-to-five, seven days a week since 1959, planning on doing? He has talked about reading the works of literature that he loved as a young man. And he has talked about reading his own books again: “I read until I got tired of them,” he told Les Inrockuptibles, “just before Portnoy’s Complaint, which is a flawed book.”

And he’s handed over 1,000 pages of archival material to the biographer Blake Bailey, who also wrote a biography of John Cheever that had impressed Roth. Bailey will have Roth’s co-operation, but full control over the published results. Roth hopes his co-operation will result in a 20 per cent inaccuracy rate, as opposed to the 22 per cent he expects if he doesn’t collude. He has become his own Horatio, forsaking joy to make sure that his story is told–and told well.

Roth has played many personas in his fiction, but he has played just as many in his public life. Philip Roth, anti-Semite. Philip Roth, narcissist. Philip Roth, misogynist. Philip Roth, subject of tell-all memoir.

Critics of Roth (and they are legion – Emily Nussbaum casually alludes to Roth as a score settling revenge-seeker in a recent New Yorker review of HBO’s Girls and the Internet is abuzz with people aghast that this retiring chauvinist should receive so many accolades) will have their ire raised by the fact that not a single Roth ex-wife or love-interest is mentioned by name in the documentary, nor is there any reference to Claire Bloom and her scandalous tell-all memoir Leaving a Doll’s House, in which she depicted Roth, her partner of 17 years, as a mean, vindictive brute. Freud, as well as Roth, knew that omission was as grand as admittance. Yet one can’t help but feel that there is something distressingly honest in this boring portrait of Roth, a man who gave, as he stressed in the interview in which he announced his retirement, his life to fiction.

The real Roth is best accessed through his work, through the many indelible characters he was able to create, through the voices that he animated so profoundly. Roth is to be found in the secluded musings of late Nathan Zuckerman (The American trilogy: American Pastoral, I married a Communist, The Human Stain), through his own non-fiction (the interesting and uncompromising The Facts: A Novelist’s Autobiography and the poignant and heart-breaking work of a son mourning a father, Patrimony), through the sex-crazed voice of Portnoy, and through the neurotic insecurity of David Kepesh. The real Philip Roth, if there is one, remains illusive.

In 1983, Roth was interviewed for The Paris Review’s ‘Art of Fiction’ series. Hermione Lee brilliantly outlined in the introduction the seriousness and thoroughness with which Roth submitted to the process. They talked forever. The tapes were transcribed. The transcriptions were revised. The revisions were revised. The revised revisions were revised again. In the end, it’s as good a portrait of Roth as any – one that should send readers back to the books. For if there is a Philip Roth it is somewhere spread over the countless voices and stories in those 31 works–all competing for a small dose of sanity in a crazy world. Asked to describe himself then, Roth offered this humble statement: “I’m very much like somebody who spends all day writing.”

What will he do now?

American Masters Philip Roth: Unmasked premieres nationwide Friday, March 29 at 9pm on PBS (check local listings) in honor of Roth’s 80th birthday on March 19, 2013.