Welcome to the future of reading

A new multimedia novel is tapping into students’ love of technology and film

Share

Once upon a time, middle-school teachers Krista Berzolla and Lauren Willey were on the hunt for new ways to keep students reading, a struggle at a time when kids, ordered to peel themselves from their screens, if only for dinner, have a tantrum. Around half of the students in their Greater Saskatoon Catholic school classrooms are avid readers and, of those, most are fans of dystopian series such as The Hunger Games and Divergent, both of which have been made into movies. But other students aren’t reading for a variety of reasons, including lack of confidence and struggles with comprehension. Recent studies show that while North American students still read for pleasure, they are reading less than previous generations, likely because they are spending so much time online. Berzolla and Willey set out to find a way to engage all students by tapping into their love of technology and film.

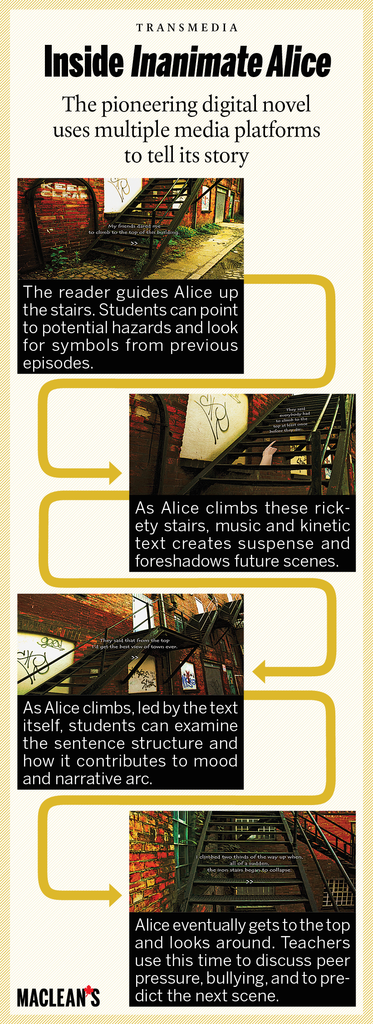

Enter Inanimate Alice, a digital novel by Canadian author Kate Pullinger, in collaboration with British-Canadian producer Ian Harper, first released in 2005. It is widely considered a pioneer in what is also called transmedia, a modern literary genre that combines multiple media platforms to tell a story. Welcome to the future of reading.

Inanimate Alice is about a young girl and aspiring video-game designer who travels the world—from China to Italy—with her mother, father, and imaginary friend Brad. Through text, games, pictures, sound and video, the audience is immersed in Alice’s world as she navigates adolescence.

Berzolla and Willey were some of the first Canadian teachers to use Inanimate Alice in class when they presented it to Grade 7 students in their district last fall. “The advances in technology are changing the ways kids read, so the way we teach needs to change,” said Willey. Inanimate Alice, with its impressive audiovisual effects, appears no different from a video game. But its driving force is the pithy narration and clever use of literary devices. “With this program, the walls between the written text and the multimedia world are broken down, and kids who are reluctant to read tend to be drawn in,” said Berzolla. They have seen encouraging results: Reluctant readers are discovering a passion for literature, including print, and those who were already reading are being inspired to write their own stories.

For Pullinger, this isn’t a surprise. She knows that simply flowing text onto a digital page, say, in an ebook, won’t keep young learners interested in reading, nor enhance critical-thinking skills. “It’s incumbent upon us to be thinking about the space for literature in the digital future, and Inanimate Alice is an early attempt to engage with that evolution,” said Pullinger, who moved to London in her 20s after dropping out of McGill University and doing a stint at a copper mine in the Yukon, where she had a job crushing rocks. In 2009, she won the Governor-General’s award for her novel The Mistress of Nothing, and now teaches creative writing and new media at Bath Spa University. “There are the endless stories about the novel being dead, that the end of reading is imminent. This is not a view I would ever subscribe to, because I do think human beings have a fundamental desire to tell and be told stories,” she said. “We’re only just at the beginning of what might be possible next, when it comes to new ways to tell these stories.”

Although originally intended as an entertaining prequel to a screenplay written by Harper, Alice is now famous in many countries—but not in Canada—after teachers embraced it as a fresh way to teach literacy and creative writing. In 2012, Inanimate Alice became the first digital text endorsed by Australia’s national education body and was awarded best website by the American Association of School Librarians. The Australians loved it so much, they collaborated with the creators to have the characters visit Melbourne in a series of special episodes. It has been translated into several languages, including Indonesian and Japanese.

Five of the 10 episodes planned for the series are available for free online for computers and mobile devices. The fifth episode, set in England, was released on Dec. 1; the sixth will be released in 2015.

Pullinger says that, because children are being raised with touchscreen technologies, authors must produce engaging content for that medium. At the moment, there’s a dearth of interesting digital content to use in class. “If this generation grows up not reading, whose fault will that be? Not theirs,” she said. And the way we tell stories must keep up with digital platforms, such as Twitter and Instagram, that have become more visually oriented. “I don’t really know what effect that will have, but I don’t think it’s threatening,” she said.

The most exciting part of transmedia is that it affords audience participation that hasn’t been possible until now. In 2009, a Google alert notified Pullinger that a new Inanimate Alice episode had been released, even though she was still working on it. She discovered students in Kentucky were creating their own episodes for class using Webmaker and PowerPoint. “It was a eureka moment, a real eye-opener that made me realize what interactivity really is, and what is possible with new forms of online literature,” she said. “We immediately thought we needed to somehow embed this within the project.” Since then, she and Harper have been remotely mentoring students around the world, including the Saskatoon students, as they create their own episodes. “Kate Pullinger’s concise writing fits so well and, combined with the audiovisual material, creates a dramatic effect that gets kids emotionally involved in an entirely new way,” said Harper.

For Marty Keltz, the Toronto-based producer of children’s programs, such as The Magic School Bus and co-founder of CritterKin—a transmedia book that uses animal characters to teach empathy and critical thinking to children—the digital revolution has made reading and writing a bigger part of children’s lives than ever before. “Whether it’s tweeting or blogging, it’s up to educators to capitalize on that, not dismiss it as inferior,” he said. It’s not that books won’t be there, but multimedia storytelling will make reading experiences broad enough to include all types of students, at any reading level. “Individual children have different learning capabilities: Some learn by seeing, touching, hearing, seeing or creating,” said Keltz.

Throughout history, the pedagogy of reading and writing was geared toward one kind of learner, said Jena Ball, an educator and Keltz’s CritterKin partner. “Kids who learned differently, who had things like ADHD and dyslexia, were left out. And we need every single learner engaged to come up with solutions to the world’s problems” she said.

Storytelling will always be central to literacy, no matter what form it takes. But for Jasmine Bowles, one of Berzolla’s Grade 7 students, nothing can replace getting lost in a paper page-turner. “Most people will read digital books like this in the future,” she said of Inanimate Alice. “But I still like reading traditional books, because you can imagine it the way you’d like it to be. There’s more freedom.”