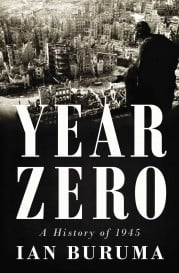

Year Zero: A History of 1945

By Ian Buruma

For the victors of the Second World War, 1945 was “Year Zero, the perfect moment to create a new society on the ruins.” Sometimes such delusions bore great fruit: Japan was transformed from a militarist aggressor into a peaceful economic giant, and genocidal Germany somehow gravitated toward the bosom of a united Europe (at least, its Western half did). Elsewhere, uncontrolled possibilities in the postwar chaos thrived before the re-imposition of order. Spontaneous and exultant postwar sex—to the great joy of liberating Canadians soldiers in Holland, especially—quickly ceded its place to a status quo of prudery. “Fraternizing” Dutch women would have their hair cut off by moralizing mobs. There was also a slim and bloody window for revenge in peacetime: for victorious Russians to rape German women, for post-Vichy France to torment female “horizontal collaborators,” for brigades of Jewish soldiers to assassinate Nazis and, most perversely, for anti-Semites to kill or steal from Jews returning from death camps.

Much of what the victors of the Second World War dreamed—often improbable—remains with us. Yes, understanding 1945 helps us understand today. Yet many of Ian Buruma’s best stories represent failed possibilities and historical dead ends. Buruma is sufficiently alive to contingency to refrain from tidying up history. He trusts the reader with such complexity.

The scope of this book is narrow in time but breathtaking in geography. In any given chapter, Buruma pursues his arguments with examples from France, Germany, China, the Philippines, Algeria, Korea, Japan, Syria and more. Buruma credibly pulls this off, because he has lived in so many places and speaks so many languages. But it comes at a cost: There are few recurring characters, and readers had better be paying enough attention to absorb crash courses in Indonesian nationalism in just seven pages, or in imperial European duplicity in Syria in a mere three. If they can manage to hold on to themes without fretting about the kaleidoscope, they’re in for a treat.

Andrew Stobo Sniderman

Visit the Maclean’s Bookmarked blog for news and reviews on all things literary.