China’s great wall of Canadian sound

Canadian bands like Hollerado are making inroads with Chinese audiences hungry for western rock ‘n roll

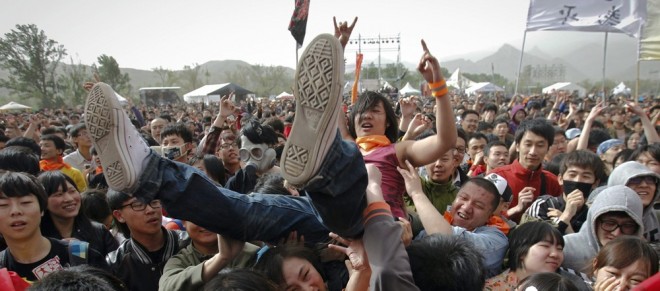

A Chinese fan is lifted up by others during the Midi Music Festival held at a park in Mentougou District in Beijing Saturday, April 30, 2011. (AP Photo/Andy Wong)

Share

When Ontario rockers Hollerado booked their gig in Yangshou, China, they knew things wouldn’t run as smoothly as they do at home. But nothing could have prepared them for when they saw their backline—the set of amps a club provides for bands—roll up to the venue in a trailer hitched to the back of a bicycle. “He had apparently been biking for four hours to get it into this town,” says Menno Versteeg, the group’s lead singer. So hungry are Chinese fans for rock music that the promoter had a set of old Soviet amps from a nearby town peddled in specifically for the group’s set. “It reminded me of when I heard rock music for the first time, the effect it had on me,” says Versteeg says of their dedication to making the show a reality. “You could you see it in their eyes.”

When Ontario rockers Hollerado booked their gig in Yangshou, China, they knew things wouldn’t run as smoothly as they do at home. But nothing could have prepared them for when they saw their backline—the set of amps a club provides for bands—roll up to the venue in a trailer hitched to the back of a bicycle. “He had apparently been biking for four hours to get it into this town,” says Menno Versteeg, the group’s lead singer. So hungry are Chinese fans for rock music that the promoter had a set of old Soviet amps from a nearby town peddled in specifically for the group’s set. “It reminded me of when I heard rock music for the first time, the effect it had on me,” says Versteeg says of their dedication to making the show a reality. “You could you see it in their eyes.”

Hollerado are one of a growing number of Canadian bands heading to China in the hopes of tapping into the country’s newfound appetite for rock music, particularly from the West. And Canadian bands are finding themselves well positioned to take advantage.

“In China right now there’s a generational gap between the under-25 and over-25,” says Tyl Van Toorn, executive producer of the TransmitCHINA conference, an annual industry event that brings Canadian and Chinese creative content sectors together. “The under-25 crowd, you’re seeing a very significant interest in not just commercial prosperity. They’re looking for international cultural prosperity.”

For decades China has played Moby Dick to western business world’s Ahab; an untapped market that remains out of reach for all but the savviest entrepreneurs. With a population of well over one billion even cracking fractions of a percentage of its populace is a massive success for any company. But the country’s size is also what keeps it so elusive. We need China, they don’t need us.

“It’s like the prom queen,” say Jon Campbell, a Toronto native who spent the last 10 years working in China as a concert promoter and booking agent. “The world wants China, so China can just sit back and say, ‘Yeah, come on over. Maybe we’ll pick you.’ ”

Toorn describes China as a rapidly changing place but interest in western music remains miniscule when compared to the country’s dominant pop music industry. “Ninety-nine per cent of the Chinese music scene is pop,” he says, “and Chinese pop is not necessarily of any interest to western markets. But even fringe appeal in China can translate into a sustainable audience and in China trends really move fast.

To see it first hand, you need only look at the history of rock music in China. “The oldest generation of rock people in China have been listening since 1978 at best,” says Campbell, author of the book Red Rock: The Long Strange March of Chinese Rock & Roll. After the death of Mao Zedong in 1976, western artists like the Carpenters and Jon Denver started making their way into the country. Despite their rather milquetoast status here, to Chinese audiences, their music was a revelation. Much like British teens assimilating American blues records in the ‘60s, hip Chinese youth sucked up whatever Western music they could get their hands on.

Wham! were the first major Western group to perform in the country in 1985. By 1986, China had its very first homegrown rock star: Cui Jian. The early 90s saw Chinese hair metal acts achieve arena status, while a burgeoning underground gave birth to local grunge and punk bands. By the turn of the century, a new generation of wired Chinese youth were consuming rock music at breakneck pace. Bands were formed, taking inspiration from artists they read about on western music sites like Pitchfork or heard through China’s wildly popular social networking sites. “Popular music is getting bigger because there is a more mature Chinese consumer base that wants it and is acculturating it,” says Toorn. “It’s not being imported verbatim anymore. It’s being imported and re-acculturated inside social media, in context of Chinese culture.”

Monetizing this hunger for rock music has proven difficult. “There never has been a physical market in China,” says Campbell. Even in the 80s, bootleg tapes with hand-written sleeves were sold in legit record stores. “From the earliest days there’s been this combination of grey and black markets.”

“It’s pretty much the wild west right now in terms of the music economy,” confirms Piers Henwood, Tegan and Sara’s manager and member of Jets Overhead who took part in the 2009 Transmit tour. Like in the West, online piracy is rampant. “You don’t even have to be that savvy to get music through illegal means in China,” says Campbell. “Although it is getting harder.”

Both Campbell and Toorn give much of the credit for that fact to deals brokered at Transmit.

The conference was born out of a similar conference TNT produced in Vancouver. Heritage Canada and the Government of British Columbia approached them about producing a similar event at the Beijing Olympics to “present a sophisticated view of Canadian culture to the Chinese and to the international community,” leading up to the winter Olympics in Vancouver.

“We immediately realized that yeah, it’s great to showcase. But out of respect to the Chinese community, if you don’t commit to a long term strategy of relationship development, you’re not taken very seriously.” TNT quickly committed itself to carrying on the conference for at least five years.

Transmit isn’t the first government backed group to attempt to break through China’s icy veneer. European countries regularly send trade missions, often with artists tagging along. But Toorn says this is the wrong approach. “If you wave the flag it will look like these artists are not there on their own. And China, despite how it’s governed is very much an enterprise-, innovation-driven country like America. You don’t want to necessarily be perceived as needing subsidies or needing to be within a trade delegation.” Transmit plays down the government subsidies it receives. “It doesn’t really speak to cool. And the kids there can smell it, just like the kids here can smell it.”

Touring then seems to be the best way for a band to prove themselves to increasingly discerning Chinese crowds. With over a hundred cities with populations over one million, and food and accommodations cheap if bands are willing to sleep and eat where the locals do, the country looks perfect for extended bouts of touring. But getting there can be incredibly expensive—the bands on Transmit’s tours rely on FACTOR grants from the federal government to offset travel costs—and when applying for visas, bands have to submit the lyrics to their songs and a set list they must adhere to for the duration of their stay, although no one’s quite sure if anyone is actually keeping tabs. California punks NOFX reportedly submitted Billy Joel lyrics on a recent trek over.

It’s no coincidence that the Canadian bands Transmit brings over are, at best, mid-level club groups. The cost of seeing an established artist, like Sonic Youth who played Beijing and Shanghai in 2007, is far beyond what the average Chinese kid can afford. “If the band’s at a certain level and expects a certain degree of professionalism, production and predictability, then I think the Chinese market can introduce some variables that might not work,” says Henwood. “But if the band is looking for life experiences and willing to roll with the punches then I certainly would recommend they go.”

Both Hollerado and Jets Overhead have returned for subsequent tours following their 2009 Transmit gigs, making special appeals to directly court their Chinese audience; Jets Overhead has shot a music video for their song “No Nations” on the first tour, prominently featuring the cities they had visited. Hollerado went so far as to create a Chinese version of their website and recorded two songs in Mandarin. “It’s very important that you’re speaking the language, that you’re translating your story into their culture,” says Toorn, “you’re not just maintaining an Anglo-American approach to your product.”

Going back without government grants, or the financial backing of one of the growing number of local Chinese government sponsored “tourist festivals” (calling it a rock fest is still taboo there), that guarantee international acts relatively large payouts isn’t viable. Even if 200 people show up for a gig, they’re paying $5 at best to get in. “I don’t think there’s a reliable market for the music that we play in China,” says Alex Cooper, singer and guitarist for Parlovr, who played last year’s Transmit tour. “At this point it’s kind of hard to tap into anything there financially.”

Even if a tour isn’t a money-making scheme today, the investment in China is important, says Toorn. Developing relationships is key in Chinese business. “The great thing about China is once something gets going it just rolls like a wave. All of a sudden there’s this explosive energy,” he says. “If you don’t have your relationships in place and you don’t have your network and you don’t understand how to operate on the ground there, you’re going to have to move really fast. If you’re not connected to it, you might miss it.”

Versteeg sees it a bit differently. “You can’t really be in this business to make money,” he says. “What’s the difference between making no money in China or no money here?”