Could we go to war again?

During the Great War, Canada answered a call to duty with sacrifice that seems unfathomable today

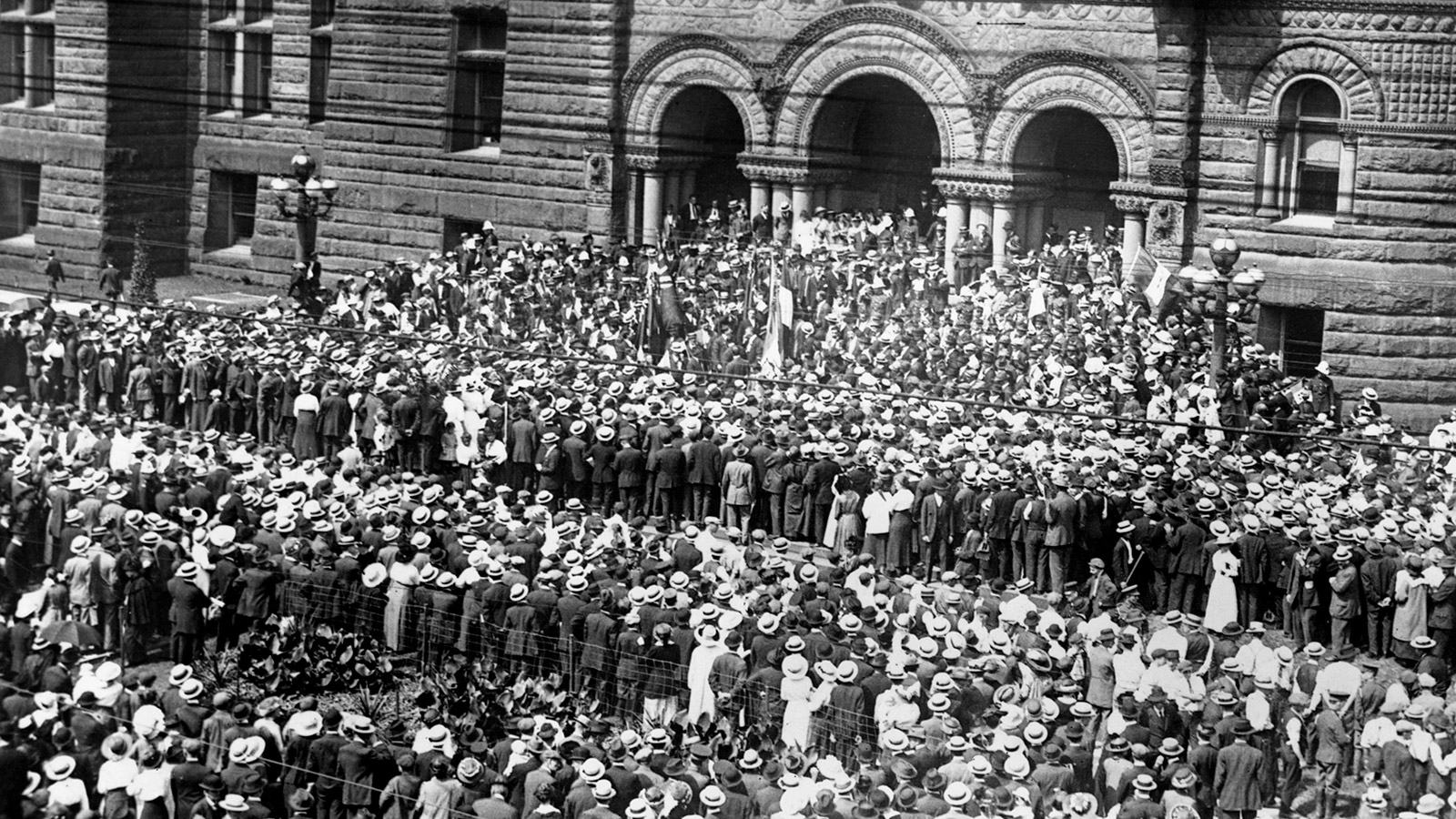

Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis

Share

Mountsberg, Ont., was once a village with a future. In the early 1900s, it boasted a general store, a blacksmith, a post office, a steam sawmill, two churches, a public school and perhaps 150 residents in town and on neighbouring farms. Located between Guelph and Hamilton, with a nearby railway siding offering easy access to Toronto, Mountsberg was on the verge of becoming a major rural service centre. Then came the Great War.

Like most of Canada, Mountsberg responded quickly and eagerly to the call of king and country in 1914. And, along with the rest of Canada, by 1918, it was forever changed.

Two dozen men from Mountsberg—about half the young male population—went off to war. Four years later, six of them, including 21-year-old Roy Mount of the village’s founding family, were dead. Many others, including the local Methodist minister and Erle Glennie, the popular schoolteacher who joined the Royal Flying Corps, survived the conflict but didn’t return. The village never recovered.

“Mountsberg lost heavily in the war,” says Jonathan Vance, a historian at Western University in London, Ont. “Its young, working-age male population was all but wiped out or never came back.” Robbed of so much of its small workforce, the village lost business to nearby competitors. The post office closed. Then the store, mill, blacksmith, school and one church. The railway no longer stopped at Mountsberg. Today, the village has largely disappeared from the map; a few acreages, some heritage buildings and an owl conservation area are all that remain. A weathered war memorial standing sentinel in an empty park is the lone reminder of its unmet potential. Like so many individual Canadians, the village of Mountsberg itself made the ultimate sacrifice in the Great War.

The First World War stands as the biggest, most deadly task Canada has ever undertaken. More young men died in the trenches of France and Belgium than have been killed in all of Canada’s other wars combined. At home, the impact was nearly as profound. Those who didn’t fight found their lives altered in innumerable ways at work and in leisure. Such universal sacrifice was accepted by most Canadians as both entirely reasonable and absolutely necessary. As a collective undertaking, the totality of the war effort thus demands consideration as one of Canada’s greatest triumphs. And yet, by 2014 standards, it also seems utterly foreign.

A century removed from the Great War, Canadians today expect their politicians to ensure our lives are made more comfortable and safe, not threatened by antique obligations of duty and national honour; we demand protection from sacrifice, not exhortations that we give more, work harder or put our lives at obvious risk. Any attempt to put Canada’s effort in the Great War in modern perspective runs headlong into the uncomfortable question of whether we still retain that apparently boundless capacity for suffering and commitment we displayed from 1914 to 1918. Would Canadians today answer a call to duty for a national project the size, scope and duration of the Great War? Could we do it again?

On Aug. 4, 1914, Britain declared war on Germany. Canada, as a member of the British Empire and lacking its own independent foreign policy, found itself at war, as well. Unlike Canada’s previous experiences with war, however—a haphazard invasion by the Americans in 1812, rebellions in Western Canada and a distant Boer War—this was very different.

“It was a total, unlimited war such as the world had never seen before, and it was felt all the way back through Canadian society,” says Tim Cook, historian at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa and author of several books on the First World War.

At the sharp end of the stick, 620,000 Canadians enlisted or were conscripted into the Canadian Expeditionary Force, about a third of all men aged 18 to 45. Of these, nearly 60,000 died by war’s end; another 6,000 succumbed to their wounds following armistice. “If you put that death toll into the equivalent of today’s population, it comes out to something like 250,000 dead in four years,” says Cook—or the entire population of Saskatoon. “Numbers like that seem unimaginable today.”

While Canada put together a proportionately larger force for the Second World War, that conflict’s death toll was a fraction of what was experienced between 1914 and 1918, due to changes in the mechanics and tactics of war, including such things as air superiority, tanks and better training. At the bloody meat-grinder of Passchendaele in the fall of 1917, for instance, Canada suffered nearly 16,000 dead and wounded. At Vimy, Canada’s most celebrated First World War victory, the toll was 10,000. Together, these two battles comprised just two weeks of fighting, but accounted for as many casualties as the Canadian army suffered during its entire 20-month Italian campaign in the Second World War. Every war is hell, of course. But the Great War was a special kind of agony.

At home, the scale of engagement was equally immense. The Great War precipitated tremendous dislocations across the entire country. The bulk of Canada’s industrial capacity was shifted to munitions production; even cement factories were repurposed to churn out shells. Likewise, the Prairie farming economy was directed to grow wheat almost exclusively. The long-term implications of these moves were only felt after the war, when the global market for shells and wheat collapsed. In fact, Canada suffered the second-most severe post-war recession of all belligerent nations. Only Germany had it worse.

To support the wives and mothers of soldiers at the front, individuals and businesses were instructed to “give until it hurts” to the Canadian Patriotic Fund (CPF), a private charity. As there was no equivalent government welfare program at the time, employees often found CPF contributions deducted from their paycheques as a form of employer-imposed tax, and this was largely accepted. “People were much more generous then than they are nowadays,” observes Vance. “The level of generosity was astounding.” Plus, everyone was expected to buy Victory Bonds to fund the war effort itself. Even children had to do their bit. Kids in Brantford, Ont., were encouraged to donate their pennies to the local Children’s Cigarette Fund, which sent smokes to the trenches.

Perhaps the most significant change brought on by the war was the dramatic appearance of Ottawa in everyone’s lives. “Before 1914, most people had very little to do with governments at any level,” says Western’s Vance. The federal government’s tiny budget came almost exclusively from customs duties and taxes on alcohol and tobacco. Equally modest were the public’s expectations of what government could and should do.

“The war created an interaction between the public and government that seems quite astonishing,” Vance says. The Great War saw the government insert itself directly into the daily lives of Canadians in new and previously unimagined ways. For the first time, Ottawa told Canadian families how they ought to live. The advice was relentless. Folks were told to skip meat on Meatless Mondays, go without heat on Fuel-less Sundays, raise backyard livestock for “Keep a Hog” campaigns and save all their bones, fat, tin and other recyclables. Federally empowered fuel and food controllers searched out and scolded wastage. Five minutes of every school day were spent instructing schoolchildren on how to save time, money and food. And everyone was expected to knit socks in their spare time.

Such intrusive public service messaging may seem commonplace today (and proved to be less draconian than the rationing and other strict controls introduced during the Second World War), but it marked a major and irreversible shift in the once laissez-faire relationship between government and citizen in Canada. The right to be left alone was gone forever.

Beyond the household, Ottawa imposed numerous other countrywide reforms, including: conscription, daylight savings (to boost production), Prohibition (ditto), women’s suffrage (a belated thank you for their role in the war effort), mandatory personal identification (for males who’d been exempted from conscription) and anti-loafing laws (to ensure such males were never idle). To keep all these transformations ticking along, the bureaucracy of government also exploded. And, as demands grew in proportion to the casualty list, government gradually accepted more responsibility for supporting war wives and mothers, taking over control of the CPF and establishing what might be considered the origins of the modern welfare state. Of course, all this had to be paid for. An excess-profits tax was collected on businesses beginning in 1916, then personal and corporate income taxes were introduced in 1918. All three were “temporary” revenue measures meant to last just as long as the war did. Only the excess-profits tax actually proved to be.

Despite all this upheaval and these new demands by government, the Canadian public had surprisingly few objections. One major reason was the deep bond between Canada and Britain. At the outbreak of war, more than half of Canada’s population was of British descent. Of the first contingent of 36,000 Canadian soldiers sent to Europe in 1914, two-thirds were actually British-born, many of whom may have signed on in hopes of a cheap trip home. Once they arrived in England, the soldiers headed to Westminster Abbey, where they ritually laid their battalion flags at the tomb of Gen. James Wolfe, hero of the Battle of Quebec in 1759. In many ways, the Great War was seen by its first participants as a continuation of a long British colonial tradition dating back to the origins of Canada itself. Perhaps surprising, the war also found early support in Quebec as a fight for democracy and freedom, although this evapourated once the conversation turned to conscription.

Pre-war Canada was also a society in which military service was considered a rite of manhood. While the full-time Canadian army had just 3,000 troops before the war, Cynthia Comacchio, a historian at Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Ont., points out that, since 1909, Canadian schoolboys between the ages of 12 and 14 had been receiving regular militia training, including marching drill and rifle firing, as part of a national program of military preparedness. “In addition to the patriotism of Canadians and our role in the British Empire, this explains why there was so little objection to the whole idea of going off to war,” says Comacchio. “The notion of war as testament to manliness was already socialized into our boys.”

If overall support for the war never wavered, as the casualty list grew, it quickly became necessary for everyone to prove their commitment to the cause. Alleged shirkers quickly learned what was expected of them. In 1917, for example, Pierre Van Paassen, a Dutch expatriate studying to be a minister in Toronto, was attacked on a streetcar by a mother who’d lost three sons to the war. “Why aren’t you in khaki?” she screamed at Van Paassen, as recounted in his memoirs. While bystanders fresh from a nearby bar grabbed his arms, “She pinned a white feather through my coat into my flesh: the badge of white-livered cowardice . . . The following day, I enlisted.”

While the imposition of conscription following the fractious 1917 election (which permanently turned Quebec voters against Robert Borden’s pro-conscription Conservative party) solved the manpower problem brought on by trench warfare, equally problematic was Canada’s money requirements. The Great War may have begun as an expression of loyalty to the British Empire, but a pragmatic need for cash pushed Ottawa straight into Wall Street’s arms. “The war shifted Canada’s economic focus from London to New York,” says University of Toronto historian John English, a biographer of Borden’s. Along with Quebec’s distrust of the Conservatives, income tax and the origins of the modern welfare state, this connection to the U.S. economy is yet another “temporary” aspect of the war that continues to this day. Ottawa also discovered, to its surprise and delight, that it could borrow from Canadians themselves. In 1915, the federal government attempted to raise $50 million by selling Victory Bonds to its citizenry. It raised twice that, and double again in future campaigns.

While Canadians at the front were being bombarded in a very real sense, Canadians at home faced an equivalent, though figurative, bombardment of demands, obligations, intrusions and sacrifices. Everyone was expected to do his or her bit—then do a bit more. Could we repeat such an effort today?

Certainly, the prospect that we will ever face another world war is, thankfully, remote, for reasons of technology and strategy. The nuclear option makes prolonged conflict between major powers highly unlikely. And asymmetric warfare, such as the decade-long “war on terror,” asks very little of the general public, other than longer lineups at the airport and more closed-circuit cameras. Yet the relationship between country and citizen has also changed significantly in the past century. Canada no longer exists as an expression of national honour or patriotism to be fulfilled by public effort. Rather, governments are now expected to serve and satisfy the public itself and, most important, protect us all from sacrifice.

“Canada today is certainly not the Canada we had then,” observes Darrell Bricker, CEO of polling firm Ipsos Public Affairs. “We have changed quite dramatically and, as a result, the ability to build a national consensus around anything is pretty hard.” Compared to the homogeneous loyalty of English Canada in 1914, our modern polyglot country has lost its instinctive sense of duty to the Crown, or any other cause, for that matter. Plus, boys’ gym classes don’t include rifle training anymore.

Beyond demographic and pedagogic changes that have permanently altered our skills and sense of commitment, Ottawa may have also lost its capacity to foot the bill for unlimited wars or other similarly grand national projects.

Between the beginning and end of the Great War, Ottawa quadrupled its spending, while the national debt rose even more: from $434 million in 1913 to $2.5 billion by 1918. Such an expansion is all but impossible today, says Don Drummond, former chief economist at the Toronto-Dominion Bank and federal associate deputy finance minister. “There’s a limit on how much you can tax an economy, and that room is already used quite extensively now,” he says. The opportunity to invent new and lucrative taxes, however temporary, is long gone.

It’s true that during the Great Recession of 2008-09, the federal government was able to turn sharply from a balanced budget to a $55-billion deficit, but this was, proportionally, a minor hiccup. “No government in the world could sustain that level of deficit financing for long,” says Drummond. “They all freaked out at the debt buildup after just two years.” And while the wave of austerity that swept across Canadian provinces in the mid-1990s—electing Ralph Klein in Alberta, Roy Romanow in Saskatchewan and Mike Harris in Ontario—may offer something of an analogy for voluntary fiscal suffering delivered via the ballot box, “the public’s capacity for sacrifice these days is pretty tepid and fleeting,” Drummond says.

Beyond an economic catastrophe, it’s not clear what other modern issue could rally Canadians today to a common cause. Climate change is often suggested as a predicament demanding a similar call to action, yet its track record suggests an underwhelming enthusiasm for any concomitant sacrifices. (Consider Stéphane Dion’s Green Shift platform in the 2008 federal election.) “Global warming is actually a good example of the public’s rejection of what they consider elite opinion,” says Bricker. These days, no one is prepared to make a massive personal sacrifice simply because some politician tells them it’s their duty to do so.

Of course, the most obvious and fulsome parallel to the Great War is Canada’s military experience in Afghanistan. And, once again, the evidence suggests that a repetition of Canada’s willingness to accept sacrifice and disruption as occurred in 1914 is highly unlikely.

More than 12 years, 40,000 Canadians served in Afghanistan. Of these, 158 paid the ultimate price, the highest Canadian military death toll since the Korean War. While every death is a tragedy, it can’t be overlooked that 158 fatalities would have been considered a lucky day in the trenches—or a few minutes in the bloody No Man’s Land of Passchendaele. The overall fatality rate during the First World War was nearly 10 per cent. It was four per cent in the Second World War. In Afghanistan, it was less than half a percentage point.

Despite the relatively light death toll, however, there’s little question that those 158 deaths loomed large in Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s decision to pull Canadian troops out of Afghanistan, a move completed earlier this year. “As the casualties mounted, it shocked all of us. It certainly shocked me,” recalls historian English, who served as a Liberal MP in the Jean Chrétien government in the 1990s. “No one thought our involvement in Afghanistan would ever require that much commitment.” Jack Granatstein, history professor emeritus at York University, notes: “While the public has always supported the troops, those 158 dead soldiers turned public opinion against the war. Harper understood that.”

But if 158 deaths in defence of democracy in a foreign land is too much for the public or government to bear, what does that say about our ability to replicate the collective capacity for sacrifice and patriotic enthusiasm on display during the Great War?

For Granatstein, author of the 1998 bestseller Who Killed Canadian History? and something of a curmudgeon when it comes to drawing attention to Canada’s military past, the reason for such a change in Canada’s appetite for sacrifice and hardship lies in the twin pillars of modern society: cynicism and social media.

“People today are pretty cynical about everything—especially the motives of their politicians—so they’re unwilling to allow themselves to get caught up in any big national projects or patriotic causes,” says Granatstein. In addition, he says televised ramp ceremonies and other media coverage marking the return of each and every body from Afghanistan, such as footage of the spontaneous Highway of Heroes audiences on highway overpasses, provided a highly visual and direct reminder of the cost of war, even though the absolute numbers were dwarfed by the Great War.

Western’s Vance agrees that cynicism and new media have become powerful forces in modern life, but sees a broader social context for our rejection of collective suffering. “We’ve become conditioned to believe bad things should never happen,” he says. “And when they do, we look for someone to blame.” Go back a century and people simply accepted that terrible things could happen at any time, he says, pointing to the Great Storm of 1913 that killed more than 200 people on Lake Huron but is little remembered today. The scales of public outrage have tilted so dramatically, Vance observes, that the reaction today to 158 deaths in Afghanistan seems equivalent to the response 10,000 deaths might have garnered 100 years ago. Comacchio agrees: “We no longer think in the same way about sacrifice or the necessity of casualties. We are horrified by every single death, as well we should be.”

Another significant factor may be the move from civilian soldiers in the First and Second World Wars to the professional army of today. When a third of the young men in a country go off to war, says the Canadian War Museum’s Cook, it becomes impossible to ignore the importance of victory. “Everyone is automatically patriotic when the entire community is involved,” he says. “If every Canadian had a family member fighting in Afghanistan, it would have been a very different war at home, as well.” For all the media coverage and attention, the vast majority of Canadians never had a personal stake in the outcome in Afghanistan. There is no Mountsberg of the Afghan war.

Then again, perhaps the current ascendancy of cynicism simply reflects a lack of worthy causes, rather than the complete disappearance of concepts such as idealism, duty and self-sacrifice. At least, that’s the perspective of John Manley, former Liberal deputy prime minister, current president and CEO of the Canadian Council of Chief Executives and chairman of a 2008 task force on the future of Canada’s military role in Afghanistan for the Harper government. He’s a rare éminence grise of Canadian politics, business, foreign policy and the military, and also something of a rare optimist regarding human nature and Canadians’ capacity to serve.

Manley argues that less has changed since 1914 than is often assumed. “The soldiers I talked to in Afghanistan all spoke of their call to duty in the same way, I’m sure, that you would have heard from young men in 1914. They all took great pride in serving their country.” Like Cook, he figures that the observed collapse in public support for the mission is linked to a lack of personal involvement. “What’s different is the fact that such a small percentage of Canadians had family members in Afghanistan, so we never had that same broad sense of national commitment or sacrifice.” Plus, he says, media, both old and new, now deliver a much broader range of viewpoints, making it harder to demonize opponents or galvanize opinions.

Presented with a calamity of sufficient urgency, gravity and clarity, Manley believes Canadians would once again rise to the challenge and willingly bear whatever sacrifices were necessary. “If there was a big earthquake in British Columbia, or some other major disaster that really threatened Canada, I think you would see the same sort of response from all Canadians as we saw in Calgary last year during the floods,” he says. “Everyone would want to help.

“People do still love their country. People are still willing to sacrifice and serve, although maybe not in the same proportion or with the same uniformity of dedication as before,” Manley says. “But I wouldn’t say cynicism has entirely replaced patriotism.” Let’s hope we never have to test his theory.