If you build it, they will carp: Mariinsky II opera house prepares for the spotlight

John Fraser on the drama behind Canadian architect Jack Diamond’s St. Petersburg masterpiece

Share

Watching the Toronto architect Jack Diamond deal with the final details of his remarkable new opera house—the Mariinsky II, as it is dubbed—in the beautiful but historically complicated Russian city of St. Petersburg is to observe a lion in winter: subdued (somewhat), at bay (for the moment), but still dangerous when he doesn’t get his way. And still determined to sign off on a building that may mean more to him than any he has done before.

Famously particular (and touchy), Diamond is the master architect of many successful public and private buildings around the world and all across his own country, but especially of performing arts houses. There are seven at current count and they have all earned his architectural firm considerable fame for delivering elegant but unostentatious exterior premises that are marvels of ingenuity inside because they actually work acoustically, in performance, as well as leaving no patron soured with a bad seat.

Through five years of relentless and often very frustrating effort in Mother Russia, Diamond has learned that to get a major building project finished there—especially a controversial project still under intense scrutiny and criticism just days before its official unveiling on May 2—you need: a) a friend at the top; and b) strong friends on your team protecting your back. You can’t do it alone and the one without the other is not enough.

Diamond’s friend at the top in Russia is the extraordinary Valery Gergiev. At 60, he is generally regarded as the greatest living orchestral conductor in the world (unless you prefer minimalist conductors who simply see themselves as “one of the team,” in which case you go next door to Finland). That reputation should be enough for any outsized artistic director, but in addition to presiding absolutely over the extraordinary and legendary Mariinsky Orchestra, Gergiev is also the artistic and general director of the whole St. Petersburg Mariinsky empire, what used to be known in the old Soviet Union days as the Kirov Opera and the Kirov Ballet. It’s all his now and he controls everything tightly—right down to the wording and design of invitations.

Gergiev is also a trusted “colleague”—“friend” might be a stretch and “associate” would be misleading—of the Russian Federation’s own maestro, President Vladimir Putin. Despite his reputation as a brilliant musician and an astute political operator, however, the Mariinsky supremo set out precipitously to get himself a new opera house a decade ago, but then found himself in an almighty pickle. Desperate to expand from the beloved but cramped and inadequate 19th-century Mariinsky Opera House (now “Mariinsky I”), he pushed a flamboyant design by the Paris-based architect Dominique Perrault. This resulted in a design for a Gehry-Libeskind-style mastodon that already had its foundations created when the whole project came to a grinding halt.

Too much glass for an opera house in snowy St. Petersburg was the official reason. Looking at the plans, you might be forgiven for suspecting that someone somewhere came to their senses. Chosen by the Russian ministry of culture, Perrault was an architect who had no experience designing theatres of any sort, and his plan was quickly dubbed “the golden potato” and abandoned, at some cost.

That’s when Gergiev came hunting for an architect who actually understood how an opera house should function. Almost inevitably, he was led to Toronto, thanks to the recent international success of the Canadian Opera Company’s Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts in that city, which Diamond and his firm, Diamond Schmitt Architects, conjured up nearly a decade ago. They got the new Mariinsky opera house project finally above ground and began the remarkable five-year dance between Diamond and Gergiev, which is about to reach its denouement in a few days.

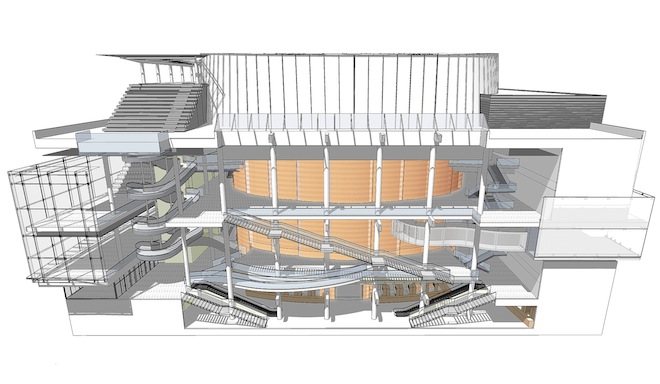

Last week, as Diamond and his architectural colleague, Gary McCluskie, the “strong friend on his team” in Toronto, toured the premises dealing with serious final issues before the handover—all under the overbearingly watchful eyes of a security system that deployed guards with serious testosterone issues—it was finally possible to see clearly that the Canadians had pulled off something of a miracle. Diamond has saved St. Petersburg from the major artistic embarrassment the French design would have represented, as well as all the unhelpful suggestions from the Russian cultural ministry—like demanding a classical exterior, which Diamond refused to countenance. He has instead produced an opera house that promises to help this extraordinary city continue to push its way to being a European capital of performing arts culture.

That’s a minority opinion in St. Petersburg at the moment, however. Even Diamond, no stranger to criticism in a long and very public career, has never had to weather brickbats like the ones being hurled at him and his firm and his design. “It looks like a shopping mall,” was one repeated verdict. One of the most repeated criticisms is the one also held against the Toronto opera house: too plain on the exterior. In St. Petersburg, this is compounded by an undeniable Russian penchant for over-the-top theatrical vulgarity. You have to absorb and appreciate the full awfulness of the interior of the old Mariinsky to understand.

Mariinsky I is where artists with no need for first names came to their great fame: Nureyev, Makarova and Baryshnikov ruled the Russian ballet world before they defected to the West from the old Soviet Union; Pavlova and Balanchine did their training here; Tchaikovsky, Prokofiev, Stravinsky and Shostakovich plied many of their epochal musical wares in their day. Looking out from the centre stage, however, you could be forgiven for thinking you had been plopped into the middle of an obscene wedding cake. The hall literally drips with rococo excess, nowhere more so than in the czar’s box directly facing the centre stage. Baryshnikov was always amused by the contrast between “Soviet realism” and Russian servility to power, which he thought was symbolized by the old Mariinsky. If he had aesthetic reasons for defecting, as well as the political and artistic ones, the hideously ornate czar’s box could be said to symbolize them.

This helps to explain some of the criticism Diamond has heard about his straightforward exterior. The St. Petersburg architect Rafael Dayarev, who heads the firm Liteynaya Chaste-91, summed up the great divide as it may never have been done before between architects like Diamond and those for whom statement always trumps function: “Perhaps it has good acoustics, a good stage and a good hall. As for architecture, or the blending of the environment, or becoming an architectural highlight, it doesn’t really tick the boxes.”

Understanding all this, Diamond is strangely unperturbed. The boxes he ticked, nicely if contemptuously itemized by Dayarev, were crucial to the project’s success. So was integrating his building into the amazing cityscape of St. Petersburg, founded by Peter the Great and still eerily evoking his vision. But with the Mariinsky II, he knows in his bones he is doing St. Petersburg a favour. The architect also believes fervently he has delivered his masterpiece.

“It’s true. I’m human and sometimes criticism can really get to me,” Diamond admitted as he turned the corner onto Glinka Avenue near the Kryukov Canal and the two opera houses—Mariinsky I and II—came into view. The new one juts out proudly but undefiantly from behind the old one with Mariinsky III— the concert hall—just beyond. Though modernist, it harmonizes not with Mariinsky I but with the presiding 17th- and 18th-century architecture of St. Petersburg.

“But the actual stuff being said or written about Mariinsky II doesn’t bother me. They can scream all they want. I know we have delivered a really fine piece of work and I know in time it will be well regarded. It is a building in scale with this remarkable city. It says something new without screaming. It does not detract in any way from the famous Mariinsky I, yet it is distinctive and elegant and it will deliver the best sound and sight lines of any opera house in the world. The glamour and excitement—the world of gilt that Russians so love—is on the inside.”

That’s not the half of it. From the outside, the golden glow from the interior is not from gold paint but from the stunning use of massive panels of pure onyx that stretch up several stories high. At night, these can be seen from blocks away and they give the building a mystical sense of wonder, beckoning you to come closer and ultimately to come inside. Diamond experimented with onyx and its translucent magical qualities when he designed the new Israeli Foreign Ministry in Jerusalem in 1988.

And yet, at its root, this is merely another performance venue and you can trace Diamond’s essential and consistent philosophy back through Montreal’s Maison Symphonique, the Burlington Performing Arts Centre, the Harmon Center for the Arts in Washington, the opera house in Toronto, the Richmond Hill Library and Performance Hall, the Citadel Theatre in Edmonton and all the way to the tiny Betty Oliphant Theatre at the National Ballet School in Toronto, unveiled in 1976: simplicity and effectiveness, in which both the performer and the viewer are honoured at the same time.

The Diamond embellishments to “simplicity” are also quietly inspired. Carving a performance space out of a stairwell at Toronto’s Four Seasons proved to be an instant success, and it has been duplicated in St. Petersburg, and even extended to a small rooftop performance area that uses all of St. Petersburg as a unique 360-degree backdrop—the only building in the city with such a view on offer. He may also have given the Mariinsky II an extraordinary cash machine: for starters, what local bride wouldn’t want to be married up there?

In the end, the entire drama of the Mariinsky II can be summed up by the saga of the czar’s box. In an initial cultural misunderstanding, Diamond could simply not believe that he was expected to have a showy “czar’s box” in the hall. “Are you sure that’s the kind of image modern Russian wants to project?” he asked. It offended Diamond’s belief in the evolutionary democratization of the performing arts. He got the answer fast. Evolutionary democracy grows at different rates in different countries. There is now a Diamond Schmitt version of a czar’s box (to be first used by Peter the Great’s almost direct successor, Putin, at the May opening). Compared to the one in Mariinsky I, it is almost Quakerish in its eloquent simplicity, but it does have a new-age chandelier on computer controls, a security-conscious separate entrance way, and the carved but unadorned arms of the Mariinsky Theatre in front.

In its own special way, that update on ancient ways is a Diamond signature on the house Jack and his team in Toronto built for a new Russia still trying to figure out how it fits into the world, but confident about its inherited artistic power and glory.