Into the abyss of black deaths in America

Wesley Lowery gets the facts in order about the Black Lives Matter movement

Share

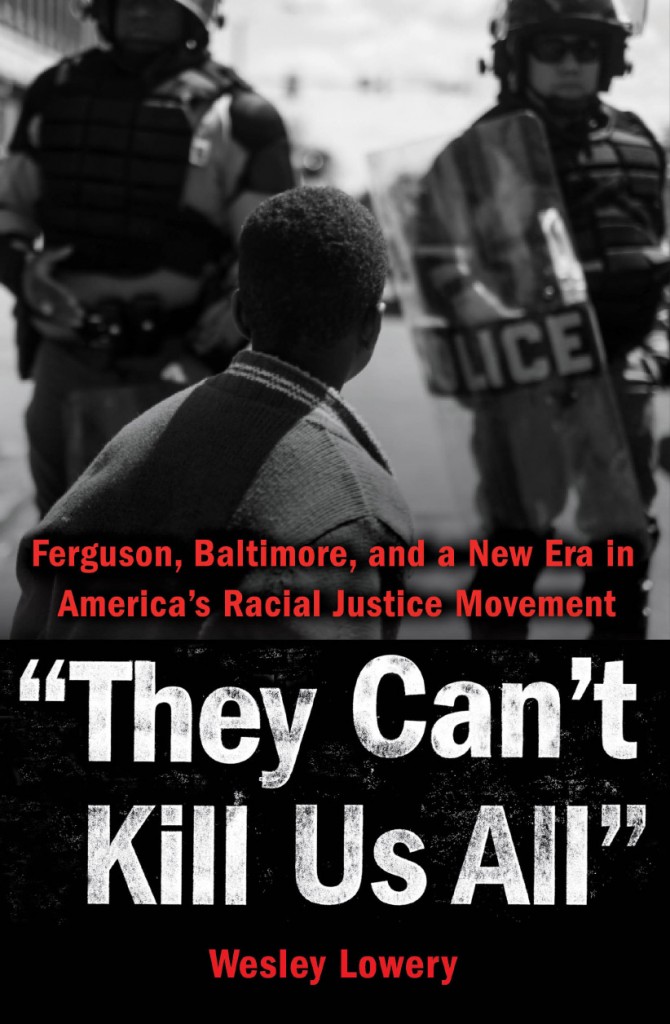

THEY CAN’T KILL US ALL

By Wesley Lowery

To the average American, the recent history of black resistance is fairly straightforward. A black teenager in Ferguson, Mo., named Mike Brown got involved in a physical confrontation with police officer Darren Wilson and wound up getting shot and killed. The stark difference of opinion between Ferguson’s black community and the facts as presented by Ferguson police led to weeks of protests, which began peacefully but descended into violence. Across the U.S., a pattern of lethal incidents involving black people and white police officers, many recorded on cellphones, sparked the protest movement Black Lives Matter.

Washington Post reporter Wesley Lowery flew out to cover the Ferguson protests, expecting to return home within a couple of days. Instead, he found himself descending into a months-long abyss of police brutality, black death and organized resistance. In this book, Lowery gives a robust accounting of characters, timelines and narratives in the modern movement for black lives. Along the way, he corrects the record on several misconceptions (e.g. the myth that Mike Brown’s final words were “Hands up, don’t shoot!”) and gives readers a proper introduction to organizers like Johnetta “Netta” Elzie and DeRay McKesson, who have reluctantly become familiar faces in the movement.

Related: How a Black Lives Matter Toronto co-founder sees Canada

Amid the recreated conversations he had with family and community members in the aftermath of fatal police shootings, Lowery—who is black—writes candidly about the struggle to separate his reporting from his own mounting frustration and despair. He discovers that, despite police officers having unilateral ability to kill on the state’s behalf, there is no accurate and comprehensive national data on police shootings. Instead, academics and activist agencies are forced to cross-reference Google searches and local police reports.

Lowery also reveals his anger at having to forgo much-needed time off to report on the killing of Walter Scott in South Carolina. “The dead looked like my father, my younger brothers and me,” he writes. “The way they were dehumanized by cable news talking heads stung me sharply, piercing the layer of detachment I had learned to acquire since being thrust into the fray in Ferguson.”

Given the frequency of lethal police encounters in America, the names and faces of the resulting protest movements evaporate quickly in the public consciousness. Through They Can’t Kill Us All, Lowery not only puts the facts in order, but gives back a layer of humanity to family members, community organizers and even news reporters that was stripped away by headlines and sound bites.