It’s curtains for Rebecca on Broadway

Cancellation of $12M show underlines Broadway’s bizarre business model

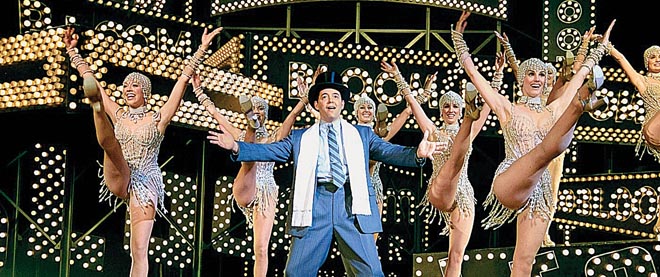

UNIVERSAL/EVERETT COLLECTION

Share

The musical Rebecca was all set for Broadway, with a theatre booked, actors hired, and an opening scheduled for November. Producer Ben Sprecher ran into just one problem with the musical adaptation of the Daphne Du Maurier novel: he started hiring people for the $12-million show based on some imaginary money promised by fake people.

Mark Hotton, a Long Island stockbroker, has been arrested for making up investors and introducing them to the producer via email. “Hotton faked lives, faked companies and even staged a fake death, pretending one investor had suddenly died of malaria,” the FBI claimed in a statement. “Not only doesn’t Paul Abrams exist,” says Sprecher’s lawyer Ronald G. Russo, referring to the mysterious malaria victim, “but neither do three other people who were brought to us.”

The production was cancelled, leaving theatre observers scratching their heads about the way Broadway shows are financed. “It’s smoke and mirrors,” says Barry Avrich, a publicist and film director. “You’re building a business on an illusion that you’ve got money coming in.” The question is whether this latest disaster will shatter that illusion.

Avrich knows something about smoke and mirrors. His documentary Show Stopper, which played at the Toronto Film Festival, is about the rise and fall of Garth Drabinsky and his imprisonment for cooking the books of his theatrical venture, Livent. After spending time on that story, Avrich says the Rebecca catastrophe “is fascinating but not that shocking to me.”

Unlike major films, which are too expensive to be financed by anyone except big corporations, many Broadway shows are still sold to individuals. “You find people who have invested in shows before,” Russo explains, “and ask, ‘Do you know someone who can invest?’ ” The search for money can lead to anonymous or little-known investors, especially today, when there aren’t many well-vetted theatre supporters. “The pool of investors in today’s economy has basically evaporated,” says Aubrey Dan, co-producer of Toronto shows such as Memphis.

And whereas movie producers are hard-nosed professionals in it for the money, theatre producers are often semi-pros, in the business for the glamour of an opening night. Dan says many people put up money “just to be part of the Broadway scene.” Some theatre disasters happen to people trying to break into the big leagues: Sprecher, who had produced small shows but wanted to transform himself into a big-budget musical producer, failed spectacularly. “There’s always a dentist or an accountant who wants to escape his life and have his name on a Broadway show,” says Avrich, who interviewed Drabinsky’s colleagues and saw how the obsession with theatre can destroy careers.

Some fans feel this is all part of theatre’s appeal. Writer Scott Brown responded to the Rebecca closing with a Vulture.com article where he celebrated that there is still “room for the cynical charlatan” in the theatre world, unlike the more buttoned-down, corporate world of film or TV. There’s something entertaining about what Avrich describes as “the grand seduction of investors who are willing to put up money to be attached to something,” and it’s sometimes more entertaining than the actual productions.

Still, the collapse of a major show can’t be good news for theatre, especially since more people are seeing it as a bad financial risk. “Loving theatre is a disease, from a financial perspective,” says Dan, who shut down Dancap Productions this summer after several money-losing shows. “The odds of a show succeeding on Broadway are probably less than 20 per cent.”

But, as Avrich notes, theatre people have a way of carrying on even after calamities. “No matter how badly a show does,” he says, “these people still have the dream of the next one being a hit.” And one of those people is Sprecher, who is not giving up. “The one thing Ben has been very clear about is that he’s going forward with this production,” Russo insists. “New York wants Rebecca and he’s going to bring it to them.” No matter how risky theatre gets, some dreams never die.