Bridges of Madison County: The musical

La Traviata in a 90s romantic bestseller

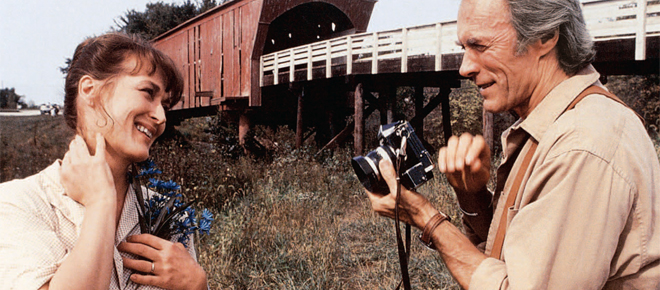

Warner Brothers/Everett Collection

Share

A couple of years ago, Jason Robert Brown, composer-lyricist of such acclaimed musicals as The Last Five Years and Parade, had just done a project with writer Marsha Norman, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of ’Night, Mother, and wanted to work with her on a big romantic musical. He says they found it in a pitch from the agent for author Robert James Waller: “He called Marsha and said, ‘We’re looking to exploit the rights for The Bridges of Madison County. We think it would make a great musical.’ Marsha hung up the phone, called me and said, ‘I’ve found it! I’ve found our La Traviata!’ ”

You wouldn’t have heard that kind of highbrow talk about The Bridges of Madison County in the 1990s, when it became the biggest-selling book of the era, a huge hit with both women and men. It was a pop sensation, like Fifty Shades of Grey, but not taken seriously. But now that the musical is in Broadway previews (after a pre-Broadway tryout in Williamstown, Mass.), starring Kelli O’Hara and Steven Pasquale, it could change the way we look at what was considered a syrupy romance.

The story of The Bridges of Madison County is certainly simple enough to make room for singing: It’s about an Italian war bride who has an affair with a handsome photographer of covered bridges. James W. Hall, author of the book Hit Lit: Cracking the Code of the Twentieth Century’s Biggest Bestsellers, recalls that the short book sold almost entirely on word of mouth and a push from now-extinct independent booksellers. “I remember hearing, at the time, many of my associates and neighbours and friends who’d read the book saying, ‘And I never read novels, but I read this one.’ ” Throw in the film version with Clint Eastwood and Meryl Streep, and everyone in the ’90s seemed to have at least some knowledge of this particular affair.

But resurrecting The Bridges of Madison County isn’t the same as adapting a classic. Hall says it “was treated with disdain by the few reviewers who took the time to write about it,” and even some booksellers were vicious. A bookstore employee told New York Times columnist Frank Rich that she was happy any time it fell from No. 1 to No. 2 on the bestseller list. Asked if he and Norman were hesitant about taking on a book with a less-than-stellar reputation, Brown says no. “We’re just as snooty and ‘sophisticated’ as anybody else. And what we saw in the book was something very honest and beautiful. And we thought, if we see that, then that’s what we’re going to write.” And, he adds, whatever the critics may have said at the time about the novel, “I felt like it had achieved a sort of iconic stature that was really beyond our ability to criticize.” Hall adds: “It’s a schmaltzy book, sappy but mythic—a combination that never hurts the success of a bestseller.”

What Bridges has that gives it that mythic status may be its take on family life. In the ’90s, it caught on because it managed to be about an adulterous affair while also being an endorsement of family values, making it now look very wholesome by 50 Shades standards. “Bridges could allow readers to have their cake and eat it, too, on this front,” Hall says. “The erotic three or four days of infidelity are balanced against the decision the lovers make to go their separate ways to preserve the sacred family structure.” Today, Brown and Norman are hoping those same themes can be used to create a serious, operatic story about hard choices: “I don’t think we take a moral stand on it one way or the other, but what the show posits is that any choice brings with it sacrifices and commitments.”

Brown says Waller was supportive, not bothering the creators about changes they’ve made to his creation. “He, in fact, had never seen a musical until he came and saw the show at Williamstown. So he did not presume to have some idea of how to make it work. But he came and was very moved and very gracious.” These are, after all, the people who could take the book to a new level. And if you’re doing an ambitious musical, it doesn’t hurt to have a familiar property to work with: “It certainly didn’t escape my attention that, up until The Da Vinci Code, it sold more copies than any other hardcover novel,” Brown says. “That can’t be all bad!”