A meal with Frank D’Angelo: Pitchman, entrepreneur, auteur

Over a boozy lunch, Canada’s beverage baron explains his latest reinvention and calls upon his Hollywood friends

Frank D’Angelo poses for a portrait in Toronto on February 18, 2016.

(Photography by Jennifer Roberts)

Share

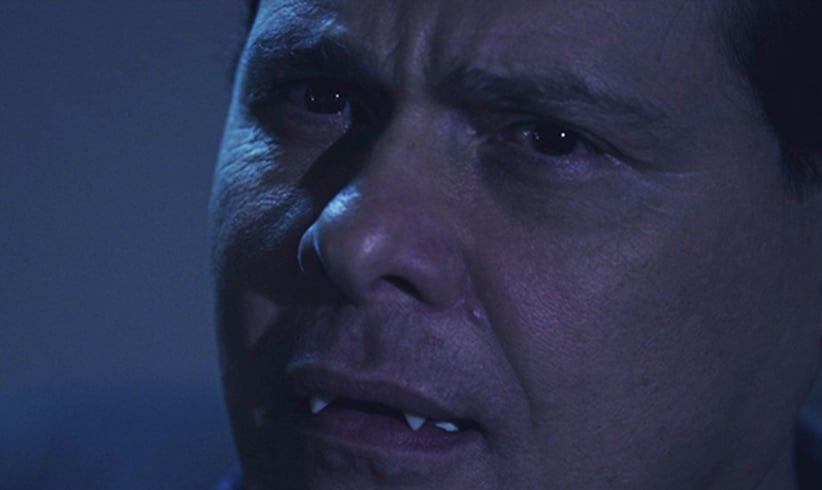

Frank D’Angelo is the writer, director and star of Sicilian Vampire. He is also the film’s producer and executive producer. The soundtrack features 42 of his original songs, plus two covers, all of which he performs. All told, the 56-year-old Toronto entrepreneur’s name appears 145 times in the closing credits. But he takes umbrage at those who suggest his transition from beverage baron to movie-maker might be driven by ego. “Why would it be a vanity project? Because I’m in it? Does Quentin Tarantino make vanity projects?” he bristles. “I do not need to make films to impress myself.”

We’re in the restaurant of a fancy Toronto hotel, at his regular table. He has ordered a $200 bottle of wine and a cheese plate before even taking his seat. Lunch—a halibut puttanesca—comes from his imagination, rather than the menu. There are two cellphones on the table in front of him. He is dressed in a cashmere sweater, and sports a couple of giant rings, a Patek Philippe watch and a bracelet thick enough to double as a collar for small dog.

D’Angelo does not lack self-confidence, or trust in his audience. Sicilian Vampire is his fourth film since his 2013 auteurial debut, Real Gangsters. (Shooting on a fifth—a political thriller titled The Red Maple Leaf—wrapped last month.) It features a cast of big, if slightly faded, Hollywood names: James Caan, Paul Sorvino, Daryl Hannah, Armand Assante, and Eric Roberts. It cost more than $5 million, and like all of his movies, has been financed solely by D’Angelo and his friends. The films’ only theatrical showings have come at off-the-radar festivals or on screens he himself rented. On Feb. 26, Vampire will receive its Canadian premiere at a Cineplex in Vaughan, north of Toronto. The theatre sits just off a major highway and is shaped like a spaceship.

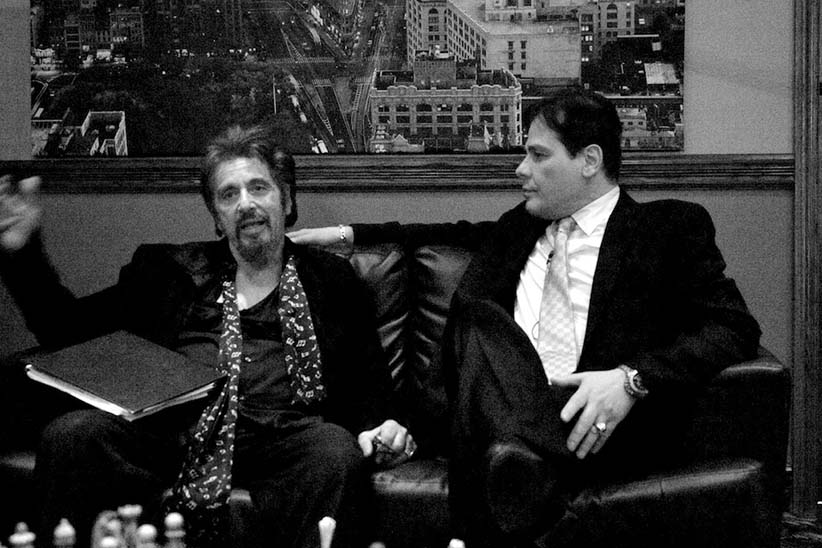

D’Angelo has no training or background as a filmmaker, other than the thousands of movies the twice-divorced night owl has watched in the wee hours when he has trouble sleeping. Although he has learned some things from doing 200-plus episodes of Being Frank, a self-produced talk show that he pays to air in the Friday midnight slot on TV stations in Hamilton and Montreal. (It is filmed in the basement of a restaurant he owns in Toronto’s theatre district, the Forget About It Supper Club.) He can also draw on a more than three-decade side career as a singer and songwriter, and the records he makes at an even more prodigious pace than his movies. “I’ve been doing this all my life,” he says. “I’ve been on stage all my life.”

But despite his vast and varied creative output, most Canadians still know him as a not-so-artful huckster. In the early 2000s, D’Angelo was the ubiquitous pitchman for his Cheetah energy drinks and Steelback beers. The commercials, featuring D’Angelo alongside disgraced sprinter Ben Johnson (“I Cheetah all the time!”) and playing net against aging hockey greats Phil Esposito and Bobby Hull, still resonate. Phil Fontaine, the former national chief of the Assembly of First Nations, happens to be dining in the hotel restaurant. He stops by the table to introduce himself and talk about how much he liked the spots that used to run in high rotation on Hockey Night in Canada.

That phase of D’Angelo’s career came to a crashing halt in 2007, with his exit from his beverage empire and an ensuing $120-million corporate bankruptcy. Steelback no longer exists, but Frank is back in charge of D’Angelo Brands, a food and drink company that manufactures Arizona Ice Tea, and private labels for grocers. And he is still, somehow, friends and partners with the guy who was owed all that money—Bernard “Barry” Sherman, one of Canada’s richest men and the co-executive producer of Vampire.

These days, the product D’Angelo spends most of his time pushing is himself. In addition to the weekly talk show, he hosts a daily sports gab fest on his own Internet station, NextSportStar.com. He’s about to go on the road for a concert tour with a 15-piece band, with stops in Halifax, Moncton, N.B., Niagara Falls, Barrie and London, Ont. And there’s the promotional work for Sicilian Vampire. After the Canadian debut, D’Angelo plans to place the film in 20 independent theatres in the U.S., mostly in New York and Florida. “A lot of people are clamouring to see this film,” he says. The Blu-Ray DVDs, which come with a bonus soundtrack album, I Want to Live Forever, have already been produced and packaged.

D’Angelo says he did extensive research into vampires for the script, but wanted to play with the genre’s conventions. The elevator pitch is Goodfellas meets From Dusk Till Dawn. He plays mob boss Santo Trafficante, who during a cards-and-drinking weekend with his crew, gets bitten on the neck by a bat that has stowed away in a box of Dole bananas. Daryl Hannah is his wife, Carmelina. Paul Sorvino plays his rival, Jimmy Scambino. And James Caan is professor Bernard Issaacs, a physician-folklorist.

After Sicilian Vampire premiered at the Big Apple Film Festival in New York last November, Vanity Fair ran a piece on its website that asked the question, “How did an Oscar-nominated legend end up in this painfully amateurish horror film?” D’Angelo claims that the review was rife with errors, including the claim—which came via a Globe and Mail story—that he pays his actors in cash. “That guy’s a piece of s–t,” he says of the author. “Every critic we’ve encountered, it seems like they have an agenda. Would you be sensitive if someone criticized your kid? That’s me. My movies are my dreams, my feelings, my soul.”

Matters were not helped in early January when several media outlets picked up on a story about James Caan—the above-referenced legend—that originated on the gossip website TMZ. In the midst of a messy divorce from his fourth wife, Linda, Caan’s lawyers filed papers claiming that continuing health problems and his ex’s free-spending ways were forcing him to take on work that he would otherwise refuse. “I am no longer willing to take parts in films and/or television shows which detract from the 50 years I have spent building my reputation,” said the actor’s declaration, according to TMZ, going on to name Sicilian Vampire as a prime, offending example.

The movie features a great deal of day-drinking, and many scenes where Santo sits around tables eating with his confederates, telling jokes and trading jabs in both English and Italian. The Dracula aspect is slow to develop. At times, it feels more like an extended collection of videos for Frank’s music—although anyone who has harboured a secret desire to see Phil Esposito sing back-up on a swinging rendition of Just a Gigolo will be delighted. D’Angelo says he was trying to avoid “contrived moments” in Sicilian Vampire, and let his dialogue provide the emotion and energy. There is certainly no shortage of quotable lines. “Dad, how did you know those guys were bothering me?” Trafficante’s daughter asks after he suddenly appears at a dance club and lays a beating on a couple of creeps. “Sweetheart, I can hear a mouse fart,” is the reply. James Caan’s doctor seems to deliver the lion’s share of them. “The Google of the human body is the blood,” he pronounces in one scene. “Look at your skin, it’s like a baby’s ass!” he marvels in another.

The special effects budget gets blown in the violent finale, a smorgasbord of gore and prosthetics. The scene where a shirtless Paul Sorvino is surprised while enjoying a caprese salad and beaten with his own severed arm is surely worth the price of admission.

Vampire runs just over two hours, but D’Angelo laments what he had to leave behind in the editing room. The card-playing scene, for example, originally ran for 46 minutes. “It was the hardest movie I’ve ever cut,” he says. It’s a stark contrast to the shoot itself, which took just five days, on location in Hamilton, last fall. (“It looks like Pittsburgh, or New York City,” D’Angelo enthuses. “You can make it look like anything.”) As a director, he prefers a single take whenever possible, filming with multiple cameras to capture close-ups and wide shots all at the same time. For the newest movie, The Red Maple Leaf, which features most of the same cast—along with Mira Sorvino, Martin Landau and Kris Kristofferson—D’Angelo proudly describes a pivotal scene in a warehouse that took him just 22 minutes to lens. “It would have taken two days with a bullshit, 1949, two-shot set-up,” he says.

By now, the restaurant is empty but for us, and there is a second, almost empty bottle of a very delightful 2010 Tignanello on the table. D’Angelo considers a request for a moment, and then starts working his cellphones. It takes only a few minutes to get Caan on the line. The 75-year-old is getting ready to spend an unseasonably hot Los Angeles day on the golf course. Caan says the whole thing has been overblown. “It’s some stupid friggin’ post about s–t that never came out of my mouth,” he says. Shooting Vampire was fun, more like a reunion with old friends than work. It’s why he agreed to return in January to do The Red Maple Leaf. “Frank’s a complete maniac,” he says. “He’s fun to be around.” The product is the product. “People go thinking they’re going to see Hamlet. They’re not. But there’s nothing wrong with that,” says Caan. “Frank tries his heart out, and I think that’s the most important thing.”

D’Angelo is warming to the challenge, alternating between polite voice mails for the personal assistants to his stars, and incredibly profane ones for closer friends like Esposito. “Call me back, you c–ksucker. I’m going to come to Florida and punch you in the left f–king ventricle.”

Martin Landau is 87 years old, and contrary to my initial suspicions, very much alive and on the other end of the phone. He’s a three-time Academy Award nominee, and won a Best Supporting Actor Oscar for playing Bela Lugosi in 1994’s Ed Wood. An early devotee of Lee Strasberg, he has also been an acting coach to Hollywood royalty like Jack Nicholson, and still serves as artistic director of the Actors Studio West in L.A. Fresh off playing an embittered chauffeur in The Red Maple Leaf, Landau is full of praise for D’Angelo’s skills. In a business that pays scant attention to character development, he relished “the window” Frank gave him to go deep. “He’s free and lets you do good work,” he says. “It’s a creative process.”

We’re on to the port when D’Angelo reaches Michael Paré, who has appeared in all five of his films. Once the next, next big thing—he starred as Eddie in 1983’s Eddie and the Cruisers—the Brooklyn-born 57-year-old now mostly plays cops and robbers, appearing in four or five movies a year, often made-for-TV. Netflix and the multichannel universe have changed the business, he says. “You can’t just sit around. You’ve got to figure out a way to get yourself out there.” Working for D’Angelo is like improv, says Paré; you have to be quick on your feet. “The challenging part is that he moves so fast, you have to completely surrender. You don’t get extra takes.” Sicilian Vampire might be D’Angelo’s best movie yet, he says. Paré isn’t too sure who the audience is, but trusts that there is one. “What’s the viewership? I don’t know. But if Frank wasn’t making money, he wouldn’t do it.”

This is an interesting point. D’Angelo is sparing little expense on these films, despite their tight shooting schedules, renting high-end Sony 6K Red digital cameras, and at times using as many as 150 extras in a scene. His latest film required four drones, three jibs and eight cameras, he says. Throw in the salaries for his increasingly sprawling, big-name casts, and it’s easy to believe his budgets are in the millions.

Yet his return on investment is harder to conceptualize. D’Angelo’s movies are all available for purchase on iTunes, and he says they do a brisk business on the video-on-demand services offered by Canadian cable companies. (A spokesman for Rogers on Demand wouldn’t provide numbers, but said Real Gangsters had indeed performed well, for a Canadian independent feature. The subsequent movies—not so much. But expectations are bullish for Sicilian Vampires, a “punch you in the face” sort of title, he said.) D’Angelo also points to a pending distribution deal with an unnamed company for all five of his works. “We’re not gambling on them. We’ll do very well. We have star power.”

The “we” in this case is Frank and his best friend, Barry Sherman. The chairman of Apotex Inc., Canada’s largest generic drug maker, Sherman is ranked as the country’s 11th-wealthiest person, with a net worth of US$5.3 billion. “He’s a brilliant man. He’s partners in everything that I do,” says D’Angelo. “I trust his judgment. I’m out there. He’s the ABS brakes on my situation as a human being.” They met in 2002, when Sherman was selling a factory he had acquired in Tiverton, Ont., that also contained a small brewery. The relationship blossomed, with Sherman’s Wasanda Enterprises extending more and more financing for D’Angelo’s beverage dreams. At the time of the $120-million 2007 bankruptcy, Sherman was really the only creditor, and held the paper on everything Frank owned, including his home at the time, in Toronto’s Forest Hill neighbourhood.

Sherman rarely gives interviews, but D’Angelo is able to get him on the phone in short order and twist his arm. In the course of a five-minute conversation, he describes Frank as a “hard worker” at least eight times. Their business past was a disappointment, he acknowledges. “Some calculation errors were made that resulted in a substantial loss,” says Sherman, specifying that D’Angelo spent far too much promoting his brands and not enough distributing them. Yet that has no bearing on their current partnership. “When I make decisions, it’s always looking forwards, not backwards,” says Sherman. “And in terms of the films, I believe in him. The value substantially exceeds the costs.” The profits have yet to materialize, but Sherman doesn’t seem too worried. “I like helping people and Frank deserves to succeed.” We should all be lucky enough to have a friend like Barry.

D’Angelo has already settled on their next film, even as he is promoting one and editing another. The script is complete, along with seven or eight more. It only takes him a couple of days to write a screenplay, he says. “I can’t stop thinking.” The soundtrack album for the yet-to-be-made movie is already done. It’s all testament to one hell of a creative impulse.

Just why D’Angelo feels compelled to put so much of his work out there on display, in such short order, isn’t so clear. His time in the public eye hasn’t all been pleasant. In 2007, he was charged with sexual assault following allegations made by the 22-year-old daughter of a business associate. The one-day trial in 2009 ended with his acquittal, but also pointed comments from the judge who said it was a matter of reasonable doubt rather than innocence. It is a surprise, therefore, when D’Angelo brings up the Jian Ghomeshi trial over lunch. Asked if he sees parallels, he says, “My own experience was totally bulls–t and fabricated. It put my family through hell, and it will haunt me for the rest of my life. It made me paranoid.”

After the trial, he found himself caught up in a corruption scandal and facing new charges of obstruction of justice. Michael Rutigliano, a veteran OPP officer and a friend of D’Angelo’s since childhood, was hit with more than a dozen charges including fraud, money laundering, and breach of trust. Wiretap evidence allegedly captured the officer—a longtime court liaison for the force—and D’Angelo talking about steering D’Angelo’s sexual assault case to a favourable judge. D’Angelo proclaimed his innocence and the charges against him were dropped in early 2013. A few months later, the case against Rutigliano stalled, after a judge blasted the way the OPP conducted its surveillance, citing “substantial” police misconduct.

Nonetheless, it all added an even darker edge to D’Angelo’s public persona. He has always embraced his Sicilian heritage and enjoys playing on the wiseguy image, from the name of his restaurant, to his snappy patter, to his choice of roles. In Vampire, he gave his character the same name as an infamous Florida mobster. He says he has met real-life underworld figures like Joe “Bananas” Bonanno and John “the Teflon Don” Gotti. Asked why he chooses to court the stereotype, he provides a mysterious response. “Perception is nine-tenths of the law,” he says, “but it’s not the actuality of the law.”

It’s a study in contradictions: the tough guy who croons love songs, the business mogul who longs to be an artist. In his 2011 autobiography, Being Frank: The Inspiring Story of Frank D’Angelo, he describes himself as “the James Bond of the Canadian beverage world.” It is possible that this was meant as a joke. On the other hand, 007 shares a similar disdain for hiding his light under a bushel.

“I’m not fake. I show who I am all the time,” says D’Angelo. On stage, TV, the recording studio and in his films, he’s selling something that he’d like you to buy. A dream. “Everybody wants to be somebody,” he says.

Clarification: A previous version of this post said a claim that D’Angelo paid his actors in cash came from a Vanity Fair article. That claim originally came from The Globe and Mail, but was referenced in the Vanity Fair story.