The agony and the ecstasy of Turner and Timbuktu

From Mali to Mike Leigh, the Cannes competition opens with two films that find terror in rhapsodic landscapes

Mr. Turner

Share

Whether by accident or design, the Cannes competition often unfolds with a thematic cadence, as if the films are talking to each other. We’ve just seen the first two of the 18 features vying for the Palme D’Or, Timbuktu and Mr. Turner, and the parallels are striking. Though they hail from vastly different worlds—contemporary Mali and 19th-century Britain—both are landscape films about a terror that lurks behind the sublime beauty of a blank horizon. In Timbuktu, directed by Mauritania’s Abderrahmane Sissako, it’s a panorama of desert sand. In Mr. Turner, by veteran British filmmaker Mike Leigh, it’s a whorl of sea and sky. And to varying degrees, both films reaffirm our faith in the power of cinema to go beyond the surface of faraway worlds.

Timbuktu arrives with uncanny timing, given the recent horror of schoolgirls being abducted by Islamic fundamentalists in Nigeria. The drama is set in the dunes of Mali, not far from a town that has been overtaken by jihadists. A ragtag band of morality police have begun to prowl the countryside, looking for converts and targets. Puritan thugs on a mission to banish music and repress women, they at first appear so foolish and incompetent they come across as comic figures. Strong-willed, no-nonsense women put them in their place with fearless impatience. A fishmonger who’s told to wear gloves lashes out with a knife and dares her accuser to cut off her hands. When a jihadist commands a cattle herder’s wife to cover her head while washing her hair, she tells him not to look if he doesn’t like what he sees. And a young rap singer being coached to record a propaganda video about the musical sins is suddenly at a loss for words.

But we know these dolts with guns are more than a mere irritation, and the tension slowly builds, until a dispute over the shooting of a calf sets in motion a tragic course of events. As the film’s stealth narrative creeps up on us, and we wait for the inevitable, Sissako films life in the desert with vistas of exquisite beauty. In this improbable landscape, trees grow directly out of the sand dunes, their low branches swept sideways as if seeking their own shade. In a cattle herder’s home, an island of vivid rugs under an open tent, we witness moments of intimacy that take us so close to the characters we can almost touch them. Meanwhile, the sound of a lilting guitar that has all the time the world—the music that the jihadists are bent on silencing—runs like an underground stream of taboo through the narrative.

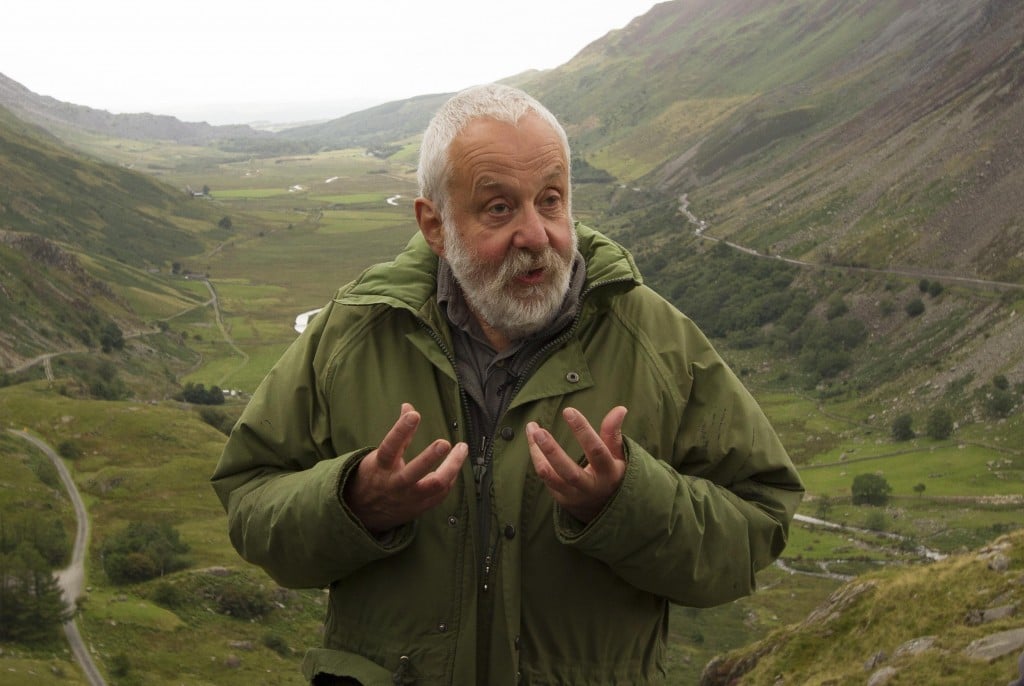

I was less moved by Mr. Turner, an alternately visceral and rhapsodic biopic of the British painter J.W.M Turner (1775-1851). This marks the tenth feature by Mike Leigh, whose Palme-D’Or-winning Secrets and Lies (1993) is now oddly being commemorated on a British postage stamp. Leigh is known for gritty, realist portraits of contemporary English life. This is only his second period piece, after Topsy-Turvy, his portrait of Gilbert and Sullivan.

Timothy Spall, one of Leigh’s favourite actors, portrays Turner as a glowering, growling, grumpy genius, an eccentric with a heart of gold and a penetrating, half-mad stare that could cut through English fog. Much of the story dwells on Turner’s messy relationships—with his beloved father, an ailing barber who works as his assistant; the painter’s bitter and neglected ex-lover who has born him two children; his doting housekeeper, Hannah, who he mounts every now and then with animal brutality; and Mrs. Booth, a seaside landlady with whom he maintains a double life.

At the core of the film is a cinematic exploration of the painter’s roiling vision. Two of the hardest things to photograph are water and genius; Mr. Turner bravely tries to get to the bottom of both, with mixed success. But as the camera scans English seascapes through the artist’s eyes, it finds breathtaking moments of sheer natural beauty.

Mr. Turner is rife with sickness, death, and countless fathoms of phlegm, as various lung infections take root. The dialogue, muttered in Cockney accents so thick it could use subtitles, becomes as murky as Turner’s scumbled canvases. Spall’s signature expression is a baritone grunt. Asked about the grunt in today’s press conference in Cannes, Spall said, it “grew organically out of this instinctive, emotional, auto-didactic, intellectual man, who had a zillion things to say but never said it. So he encapsulated it in grunts.” The actor elaborated: “He had this burning thing inside him. People who sneeze and redecorate the room have a wonderful time. Then there are those who are repressing something that’s quite pleasurable. That’s the art of the grunt.”

Like all Leigh’s films, Mr. Turner was forged from long rehearsals with the actors, who developed their dialogue without a script. Spall began learning how to paint a full two years before the shoot. He calls Turner “a painter of the sublime,” a working-class artist immersed “in the tension of man’s involvement in the beauty and the horror of nature.” Leigh, whose own crusty nature may have rubbed off on the character, says that though he did plenty of research into the painter, “you can read all the books in the world, but it still doesn’t make Turner happen in front of the camera. Turner stands on a cliff and he paints a seascape and he paints the sky. But he makes us see an experience that goes beyond the surface—living and dying.”