TIFF unearths the Stones’ taboo sex-and-drugs doc

Beyond the scenes of group sex on a plane lies a lost masterpiece of vérité

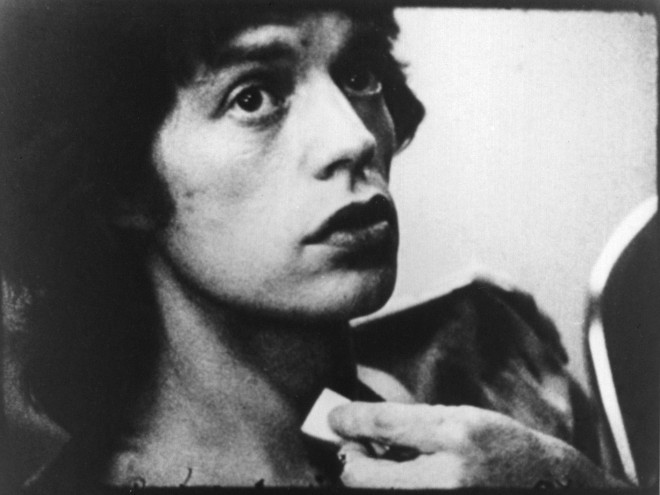

Mick Jagger circa 1971 in Robert Frank’s “C***sucker Blues”

Share

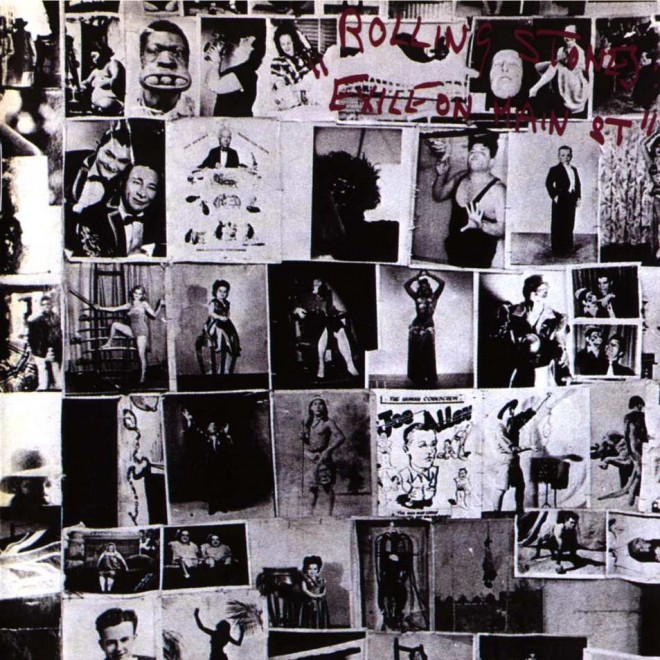

With apologies to the Rest of Canada, this is a heads-up about a rare treat for cinephiles and/or Rolling Stones fans in the Toronto area. On Jan. 17 at 6:30 p.m., in the largest cinema at the Lightbox, TIFF’s Cinematheque will hold a free screening of C***sucker Blues, Robert Frank‘s notorious backstage documentary of the Stones’ 1972 Exile on Main Street tour. It’s an unreleased film with a title based on a deliberately unreleasable song that the band recorded to fulfill a Decca Records contract. “It’s a f***ing good film, Robert,” Mick Jagger is said to have told Frank at the time, “but if it shows in America we’ll never be allowed in the country again.” When you see it, you’ll understand why. Its raw, fly-on-the-wall footage captures candid scenes of sex and drug-taking, most memorably on a plane. The Stones gave Frank full access, but then sued to prevent the film’s release, and after legal wrangling over whether the filmmaker or the band owned the copyright, a court order restricted the film to being shown no more than five times per year, and only with the director present (a Solomonic verdict that ranks with the one from an Ontario judge who ordered Keith Richards to play a concert for the blind after his Toronto heroin bust).

This is the first time Frank’s film has been shown in Toronto since he hosted a screening in 1984. I was attended that one, and what struck me at the time was the content, the backstage debauchery. But when I saw it a second time at a recent TIFF screening, in this era of celebrity sex tapes and push-button porn, its giddy scenes of boys gone bad now seem like quaint artifacts of a more innocent time. Instead, I was blown away by a lost style of filmmaking—the spontaneous composition, the shrewd editing, and Frank’s detached, deadpan perspective. Also, seeing this film in 2014 versus 1984 changes its patina entirely. I’m not talking about the film stock—TIFF is showing a richly restored digital transfer of the original 16 mm and 8 mm footage—but the way a movie filmed so utterly in the moment has crystallized into a cultural time capsule.

Unlike Gimme Shelter, the Maysles’ Altamont classic, it’s not a heroic portrayal of the Stones. Shot just two years later, it’s drenched in ennui. What can you say about a film whose junkie sound man becomes a principal character as we watch him acquire what turns out to be a fatal addiction? They don’t make vérité like this any more.

Amid the backstage circus, which is shot in black-and-white, there are splashes of concert footage in colour, including the Stones jamming Satisfaction with Stevie Wonder. But the musical episodes seem like routine concessions to fandom in a portrait that never seems besotted with its rock-star subjects. There are sublime moments that just seem to be stumbled across: a long take of Mick sitting in a hotel room with Keith as they listen to a first pressing of Happy; a time-lapse still life of Keith on a bench in an arena locker room, gradually crumpling into someone’s arms and nodding off in a posture of a rock’n’roll Pietà. And there’s a sweet excursion down a country road where the boys look for an authentic American diner while Mick gasps with relief that they’re finally not hanging around with 39 people.

That entourage, rather than the band, is the most sordid part of the scene. By the time I interviewed Mick and Keith, as they were launching slick tours staged by Michael Cohl in Toronto, their entourage had been reduced to nub, unless you count Keith’s pipe-smoking dad sitting in a corner by his amp. But in 1972, the nihilist inertia of camp-followers hangs around the band like a bad smell. Meanwhile luminaries come and go, from Dick Cavett to Andy Warhol and Truman Capote, yet Frank’s non-starstruck camera doesn’t give them a second glance.

In a sense, C***sucker Blues is an early prototype of the kind of self-portraiture that has become YouTube currency. There are a number of scenes showing band members, especially Jagger, wielding cameras. No doubt they felt they were co-authoring a kind of clubhouse home movie. And there’s a sadly self-conscious scene of Mick and Bianca in a hotel room, playing and replaying a tinkling melody on music box over and over, as they go through the motions of a marriage in ruins. Among the gems, the best line in the movie is an aside from the barely-present guitarist Mick Taylor, who walks in on a decadent tableau and says: “I’ve never seen a hotel room blessed with such limpid ecstasy.” Or maybe he said “Olympian ecstasy.” Either way . . .

No matter how commercial and corporate the Stones have become, C***sucker Blues reminds us that Jagger—who also enlisted Jean-Luc Godard to document their recording of Sympathy for the Devil—assiduously courted the visual avant-garde. Frank, whose photography graced the cover of the Stones’ album Exile on Main St, was a far cry from a mainstream guy. The Stones gave him free rein, then buried the evidence. Fortunately they didn’t destroy it.