What did Back to the Future get right or wrong? Doesn’t matter.

Don’t look ‘Back to the Future’ in anger. Focusing on what the movie did and didn’t get wrong about 2015 is a disservice to science-fiction.

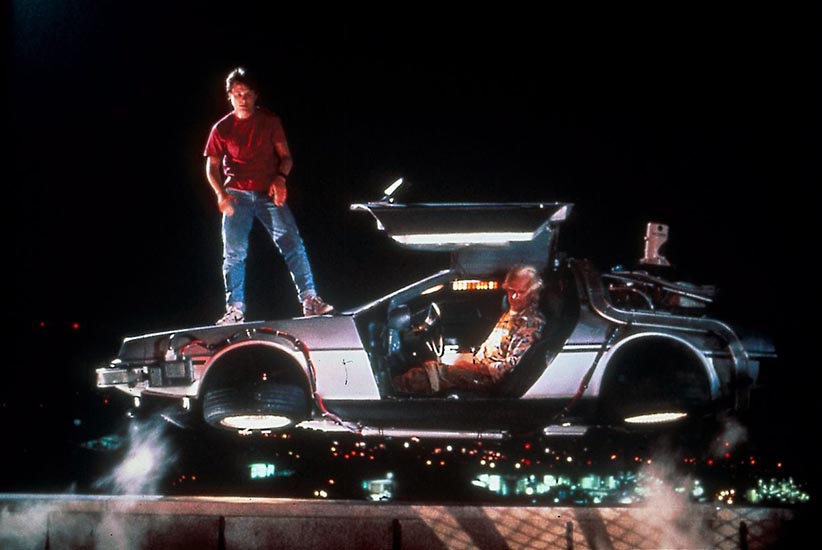

No Merchandising. Editorial Use Only. No Book Cover Usage

Mandatory Credit: Photo by Snap Stills/REX Shutterstock (2115495bt)

Michael J Fox, Christopher Lloyd

Back To The Future Trilogy – 1985

Share

On April 21, 2011, the Earth’s skies did not darken with flocks of glinting, evil cyborgs. In Los Angeles, murders have continued apace even after Sept. 25, 2010. And we have been safe from the menacing tune of Daisy, Daisy a full 18 years after the world was supposed to welcome a sentient red-eyed robot into our midst.

All this to say: Happy Back to the Future Day!

There’s much exhortation about Oct. 21, 2015. It’s the date that Marty McFly and Doc Brown punched into their rickety DeLorean time machine in the zany Back to the Future II. And it’s become, as is expected in our nostalgia-plumbing times, a branding exercise; look no further than Christopher Lloyd’s meandering paean to progress, meant to hawk the Blu-Ray version of the DVD, or Michael J. Fox’s pitch for Nike’s self-lacing shoes, or the actors driving a trash-fuelled car (sponsored by Toyota) or by the U.S. and U.K. governments getting in on the fun. Every media outlet has followed suit, festooned with lists of what the movie did and didn’t get right about our modern time.

Now, it’s hard to begrudge fun, or even branding exercises, no matter how mawkish. And there is some pleasure to take in yardstick-measuring; our hoverboard progress has come a long way, for instance. But it highlights a problem with our cultural passion for celebrating the past: By focusing on these minor novelties, we lose the artfulness of what made those movies great, and ignore the urgency of what they say about the present.

The dates above—representing the day Skynet launched its judgment day in Terminator 2, the day of the last murder in the world in Demolition Man, and the birthday of 2001: A Space Odyssey‘s HAL 3000 in a lab in Urbana, Ill., respectively—have come and gone, albeit none with the fervour we’re seeing today. They’re examples of how burrowing into the dates as a kind of novelty can pave over the beauty and the potential of a well-crafted science-fiction movie, a genre that doesn’t often receive a lot of mainstream love, but can, at their best, reflect the ills of current society in a way few others can. We do not watch the 1927 classic Metropolis, for instance, to see whether it was right about whether the world’s population lives in a fraught Tower of Babel; we watch it because it’s a stirring ode to the modern human spirit. On the other end of that spectrum, there’s the gleaming blockbuster-y District 9, from South African director Neill Blomkamp, the story of humanity’s confinement of aliens who arrived on this planet emaciated and desperate for help. But harping on the date the humans began to oppress these so-called “prawns” would bludgeon the point, which is to highlight our existing xenophobia, which all happened even without an alien threat. Science fiction, in setting itself in the future, tells us much more about the present, and that should be enough.

Our obsession with what these movies got right and wrong, too, is a bit sad; it comes off as the equivalent of a less-recognized city with a self-esteem problem celebrating a quick snatch of acknowledgement. (Torontonians know this feeling well.) The future is the exciting, thrilling unknowable; how could the present possibly measure up? The answer will always disappoint.

This is normal. It’s human nature to crave progress. Comparing ourselves, even if it’s to films made by us in the creaky past, can be a useful exercise to see how far we’ve come. And science fiction can be useful carrots to stimulate real-life advances: Jules Verne spurred Simon Lake’s submarine. Motorola was inspired by Star Trek‘s communicator devices in creating the modern cellphone. Leo Szilard read H.G. Wells’ The World Set Free, a novel about a wild future of atomic energy, and conceived the nuclear chain reaction and co-patented the first nuclear reactor; inspired by the same story’s disastrous tones, he would also advocate for arms control.

But focusing on the details in science fiction just misses the forest for the robot trees. It’s not about what it got right or wrong; it’s about the present we’re in, and the art we’re making in it. Science fiction isn’t predictive, it’s reflective. In fact, it’s exactly what Back to the Future is all about. “No one,” intones the wild-haired Doc, “should know too much about their future.”