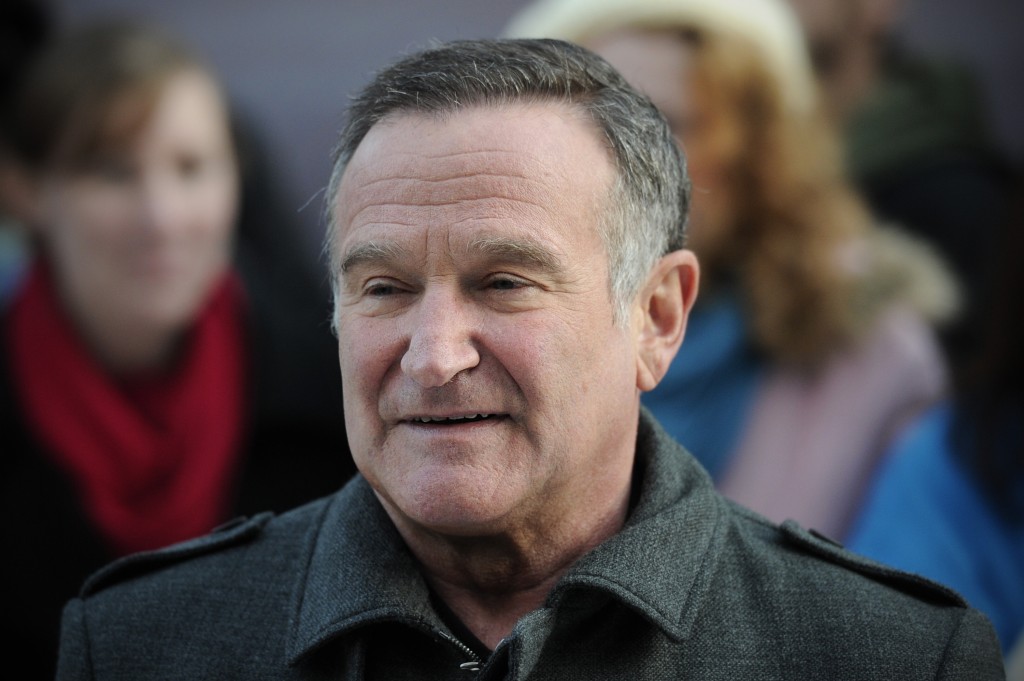

What we know about Robin Williams

Breathlessly funny at times, the comedian was a star. (What more do you need to know?) Jaime Weinman on a life and its legacy

Share

Robin Williams wasn’t supposed to be the kind of comic who would suddenly be found dead. Not any more, I mean; when he was young, he was exactly that kind of comic. The news of his apparent suicide goes to prove, if nothing else, how little we on the outside know about the people we see on TV and in the gossip columns every day.

We may think some of them have it together, that others need to get it together, and our guesses are meaningless because we don’t really know these people, even though we think we do. The reasons for Williams’s death will start to become clearer as time goes on, but we’ll never really understand why a man like him did the things he did, or couldn’t find happiness and peace despite his success and popularity. We will always be on the outside, where we belong.

As a performer, Williams was one of those comedians who was criticized by some people — myself included — for the artificiality of his style. But you don’t need to take a “don’t speak ill of the dead” attitude to point out that his comedy style was new, fresh, and breathlessly funny the first time you saw him do it — and unlike other comics, who can’t sustain that kind of rapid patter, he could do it wonderfully well all his life. (Bob Hope, for example, couldn’t do it and became bland as soon as he slowed down.) No matter how old Williams was, the first time you encountered him was always a treat, thanks to his ability to take command of whatever he was doing — a Happy Days episode, a talk show, an animated Arabian Nights — and spit out jokes so fast that you could swear he was making the whole thing up as he went along.

Related posts

- Social media reacts to the death of Robin Williams

- Paul Wells: Reflecting on the verse that Robin Williams contributed

- Robin Williams is dead at 63

Of course, he wasn’t, and that’s the thing that eventually hurt Williams’s reputation. His act was based in part on the illusion of being spontaneous, of busting into a dignified setting and reducing it to a shambles with his ad-libbing. (This is why he was such a perfect talk show guest. Talk shows used to have, and to some extent still have, a patina of dignity. The hosts wear suits and are respectable men. Williams was the guy you had on when you wanted to see that dignity challenged just a little bit.) It wasn’t really ad-libbing, or most of it wasn’t anyway, and once you saw him more often, you began to realize how much he repeated himself; because he over-exposed himself on television and in other media, he wasn’t able to maintain the illusion that he was improvising, which other, equally scripted comedians manage to do. But it sure was great the first couple of times.

It was as a movie actor that Williams was most successful, and like many big comedy stars, he sort of changed movie comedy because the formula of movie comedy had to change to fit him. He was smart enough to know he simply couldn’t do his wacky act for 100 minutes, and he was a good enough actor to keep fans from being disappointed when he wasn’t making jokes. So the typical Williams vehicle — Dead Poets Society, Mrs. Doubtfire, Patch Adams, Good Morning Vietnam — lets him do his act for part of its length, but also allows him to play seriousness, sentimentality, pathos. It was a mix you’d seen in American film comedy going back to Charlie Chaplin, and later Jerry Lewis, but Williams made that type of character his own. Again, he probably played that character once too often (and did too many scenes where everyone around him comments on how funny he is), but he was good at it. And it created a mixture that was popular with all ages: children liked him because he was silly, teenagers liked the anti-authority tone of a lot of his characters, and parents found him a basically nice boy working for good causes.

The best tribute to Williams’s skill, though it’s not the best project he did by a long shot, is Mork and Mindy. That show never should have worked, or even existed; it happened because Happy Days did a completely ridiculous episode about Richie and the Fonz meeting a space alien. But the alien was Williams, and he was so funny that he’s practically earned his own spinoff by the time the cast was taking its bows. Mork and Mindy didn’t have a great supporting cast (it changed the cast several times, but no one was popular except the two title characters) and did the same mix of wacky alien misunderstandings and light social commentary every week, but it had Williams, and people knew, in that first year of the show, that he was a star. In movies or theatre, you try to cast stars; TV makes stars, and one look at Robin Williams doing his thing was all you needed to know that he was a star.