The fraught case of the National Gallery’s plan to sell a Chagall painting

How the federal museum’s scheme to sell one high-priced painting to pay for another fell apart

The Eiffel Tower, 1929, by Marc Chagall. (National Gallery of Canada)

Share

This post was updated on June 4.

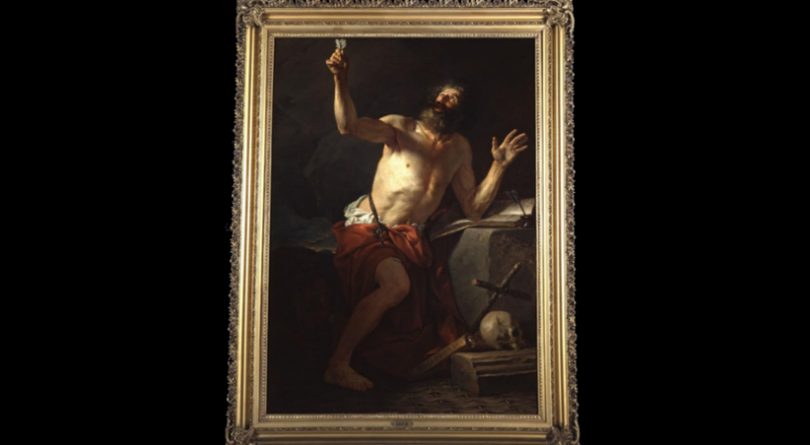

Some words don’t pop up often in the official pronouncements of government institutions. One is “ardent.” The Bank of Canada has never been ardent about anything, for instance. Nor has Canada Post. But art curators, even those who are federal public servants, trade in beauty and rarity, making ardency a live possibility. And so, on April 16, the National Gallery of Canada (NGC) declared in a written statement that buying a painting from 1779 by the French master Jacques-Louis David, called Saint Jerome Hears the Trumpet of the Last Judgment, was its “ardent goal.”

In another open letter, Marc Mayer, the NGC’s director, admitted to an “avid interest” in acquiring the David. But he faced obstacles. Saint Jerome was donated to Quebec City’s Notre-Dame Cathedral in 1938, and its Catholic church owners, apparently now cash-strapped, wanted to sell. The NGC caught wind of deep-pocketed foreign museums being interested. As well, both the Montreal Museum of Fine Art and the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec coveted the painting, although they didn’t have the several million dollars needed to make an offer.

READ: Why art galleries are quietly clearing out their vaults

Indeed, neither did the NGC. Then Mayer devised what turned out to be an ill-fated plan. After private deliberations with his board of trustees, he put a 1929 painting called The Eiffel Tower, by the beloved Russian-French modernist Marc Chagall, up for sale at the Christie’s mid-May auction in New York, expecting the luminous canvas to go for roughly $10 million. But selling art to buy art is a dicey undertaking for a public institution; Mayer said it was a last resort in this case. Still, he faced stern objections. “It’s very, very, very radical,” said Nathalie Bondil, the Montréal Museum of Fine Art’s chief curator and director general. “Our mission as curators is to keep and enrich the collections we receive from our predecessors.”

Criticism of Mayer’s strategy echoed internationally. Alexander Herman, assistant director of the U.K.-based Institute of Art and Law, expressed shock at the “deaccession,” in gallery jargon, and noted that Britain’s National Gallery wouldn’t be allowed to “sell any part of its collection on the open market.” In the U.S., though, privately endowed museums tend to dominate, and are less constrained. “So from time to time,” explained Stephanie Barron, senior curator at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), the biggest art museum in the western U.S., “many institutions do carefully deaccession works to raise funds for other acquisitions. The Museum of Modern Art [MoMA] does it, the Art Institute of Chicago does it, LACMA does it.”

Glenn Lowry, director of New York’s MoMA since 1995, and before that of Toronto’s Art Gallery of Ontario, calls himself an “outlier” among museum bosses for his advocacy of culling collections. “I don’t believe you should deaccession to fund operating costs; I think that is a categoric mistake,” he said in an interview earlier this year with In Other Words, an online art-market newsletter. “But I do believe that one should deaccession rigorously in order to either acquire more important works of art or build endowments to support programming.”

Lowry went on to stress that a gallery’s priorities should be “to program intelligently and to have as few works of art in storage as possible.” That second point about avoiding having too much art languishing in the high-tech storage facilities, which amount to the basements and attics of galleries, might have been the most surprising aspect of the whole Chagall controversy for casual gallery-goers trying to make sense of it all.

The NGC repeatedly noted that it has rarely displayed Eiffel Tower in recent years, preferring instead to show its earlier Chagall painting, Memories of Childhood, featuring a large, white goat. That’s a curatorial call. But why not let visitors to the glass-and-granite landmark in Ottawa admire both? The question could be asked about thousands of paintings: The NGC says it has only enough precious wall space to show 3,000 to 4,000 works at any given time, a mere five to seven per cent of its collection.

Saint Jerome, though, would have rated permanent display, likely in the room where it was hung—without anybody taking much note, much less mounting a protest—on loan from 1995 to 2013. In the NGC’s solid collection of historical French art, Mayer said, a “glaring exception” is the lack of a big David. But Saint Jerome, it turned out, wasn’t going to be filling that gap. After weeks of rising umbrage in Quebec over the NGC’s quest for the painting, the provincial government assigned it special heritage status, which means the canvas can’t leave Quebec without the provincial culture minister’s consent, and the province has the first option to buy it.

Even after the David was torn from his grasp, Mayer hesitated to grant Chagall a reprieve. On April 23, he and Françoise Lyon, chair of the NGC’s board, released a joint open letter, declaring that the auction would proceed as planned. If Saint Jerome wasn’t obtainable, they said, then the proceeds from Eiffel Tower would still help in “establishing a financial safety net to acquire works at risk of leaving the country,” or to pay for other major works.

Just three days later, however, they bowed to the growing pro-Chagall backlash. “With David’s Saint Jerome no longer at risk of leaving the country,” said an unsigned NGC media release, “the National Gallery’s board of trustees has concluded that it is no longer necessary to proceed with the sale of The Eiffel Tower on May 15, 2018, as originally planned.” This final capitulation, an unsigned work, was phrased in the unmistakably bloodless prose of a standard federal policy statement. There wasn’t anything ardent or avid about it.