The Man Who Got Canadians

At his best, Stephen Leacock saw through us like no one else

Share

Updated Jan. 22, 2018

His serious works, on history and economics, are beyond dated. His retrograde views on women and his certainty of Anglo-Saxon superiority is, at best, ridiculed. Even the humorous writing he was most proud of has faded badly. But in his best work, in short stories and sketches set in the conservative small-town Canada of his day, where he mercilessly made fun of his countrymen’s inflated self-importance—the writing we still read now—Stephen Leacock got Canadians, got us in a way few others have before or since. According to Margaret MacMillan, the distinguished Canadian historian and author of Paris 1919 and Nixon in China, Leacock could describe us so well, especially in our then-dominant small-town character, because “he was both part of and apart from that life. He grew up that way and then left for the big city, but he had a great love for this country, for its size and scope, its promise and beauty.”

Speaking from her office at Oxford University, MacMillan, added that writing Stephen Leacock for Penguin’s Extraordinary Canadians series “helped keep me in touch with Canada too.” And with the past. Series editor John Ralston Saul was looking for “unexpected” matches, MacMillan says, when he offered her Leacock (rather than a First World War statesman), and she leapt at it because “the Ontario I grew up in, especially in the countryside, was still very much like the world Leacock describes in Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town: very British and mostly white; a place where people inherited their political allegiances and listened in on party lines shared between houses; full of dry counties where everyone knew where to find a case of beer.”

Also at Macleans.ca: A nation in a town

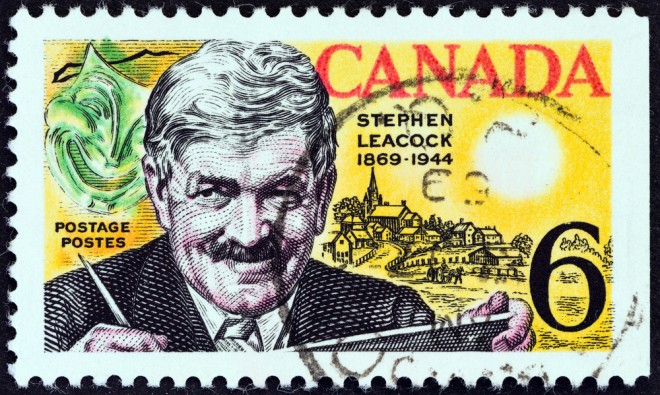

Leacock was born in England in 1869, but grew up on a farm with 10 siblings in central Ontario near Lake Simcoe, not far from the Orillia he satirized in Sunshine Sketches. Educated at Upper Canada College and the University of Toronto, Leacock received his Ph.D. in 1903 from the University of Chicago before joining McGill University’s department of economics and political science. Politically he was what would now be called a Red Tory, conservatively inclined (an ardent supporter of the British Empire) but very concerned with social justice. And that is the authorial perspective from which Leacock launched his satires—sharp-eyed as to the foibles and hypocrisies of his neighbours, but nostalgic, loyal and affectionate as well.

We still laugh at what he laughed at, MacMillan writes: “Our smug assurance that the Canadian way of doing things is the right way; our suspicions of people who do too well; how we raise our hands in pious horror when the successful slip on banana skins, but secretly enjoy the spectacle.” And it was a universal humour too. We forget now how big a star Leacock was all over the English-speaking world. Theatre producers in London’s West End wanted him to write plays for them, Charlie Chaplin asked for a screenplay, and F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote from Princeton to say how much Leacock had influenced his own writing. The New York Times ran an obit when he died in March 1944, and three months later the U.S. named one of its wartime Liberty ships the SS Stephen Leacock. MacMillan recalls how her own mother, a girl in England between the wars, knew only two Canadian writers—the other being Mazo de la Roche, author of the Jalna novels—and how pleased she was whenever she heard there was another Leacock book out.

Leacock himself claimed not to detect any particular national characteristics in his work. “There is not yet a Canadian literature,” he wrote in 1941 near the end of his life. “Nor is there similarly a Canadian humour, nor any particularly Canadian way of being funny.” MacMillan begs to differ: “How wrong he was, of course. He was in the middle of creating both.”