The Muse: A novel celebrating art

Jessie Burton’s historical fiction is elevated to fine literature

Share

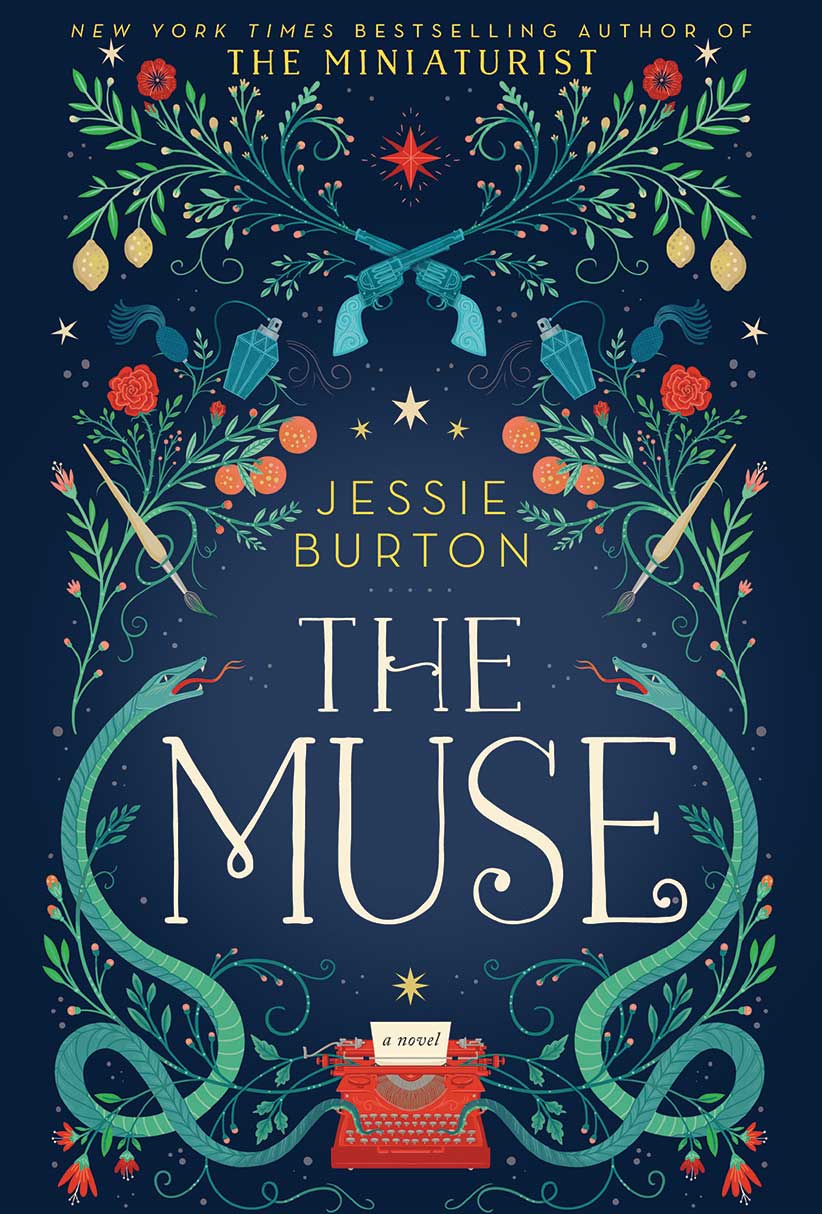

THE MUSE

By Jessie Burton

There tend to be two types of historical fiction. One is the swashbuckling, over-sexed, gender-split category. Think Bernard Cornwell’s Sharpe series for men or Diana Gabaldon’s Outlander series for women. Then there’s the obsessively researched history as a background for interpersonal drama—as likely to be classified literature as historical fiction. Think 2013’s Man Booker prize-winner The Luminaries by Eleanor Catton or the 2009 and 2012 Booker choices Wolf Hall and Bring up the Bodies, both by Hilary Mantel. Jessie Burton’s The Muse falls squarely in the literature-qua-historical fiction category. It contains two parallel storylines, one following a Caribbean immigrant in 1967 England, the other a wealthy Viennese-English family living in 1936 Spain. The storylines are connected when a painting created on the eve of the Spanish Civil War emerges in England 30 years later. Unravelling its origin forms the heart of this fantastic novel.

Burton uses 1960s slang such as “dotish” and “blimmin’ ” as effortlessly as 1930s Spanish. Her descriptions of everything from clothing and subway stops to social norms seem so consistently accurate that the relevance of the time period fades into the background. Similarly, she switches the syntax used by characters depending on the social situation they’re in. Caribbean immigrant Odelle uses slang when she’s with friends but switches to careful, almost stilted sentences when speaking to her boss. In fact, the author’s bibliography lists sources used to understand the Caribbean immigrant experience in England and life in pre-Civil War rural Spain.

The book’s great strength is how it describes art. Burton invents a 1930s artist in the tradition of Francisco de Goya, whose subversive works depict the human costs of the Napoleonic Wars, and Catalan painter Joan Miró’s abstract creations evoking the harshness of modern life. She describes painting with a notable passion, spending pages on colour choices that could easily be tedious but are undeniably captivating.

Burton’s first novel, The Miniaturist, won several awards and accolades but received tepid reviews from many critics. At the climax of her new work, Burton pillories reviewers assessing her painter’s gallery show, mocking them for self-importance and projecting their own insecurities on art. In The Muse, the harshest critic asks whether the painting is being presented as a joke, which drives curious people to the gallery in droves, making the joke, ultimately, on the reviewer. The whole scene is an unsubtle rebuke of her critics, but an effective one. After all, The Miniaturist sold over one million copies, and The Muse likely will too.