The new, even blurrier lines of the post-‘Blurred Lines’ universe

How the new ruling against Robin Thicke and Pharrell kills creativity—and will ruin music for audiences

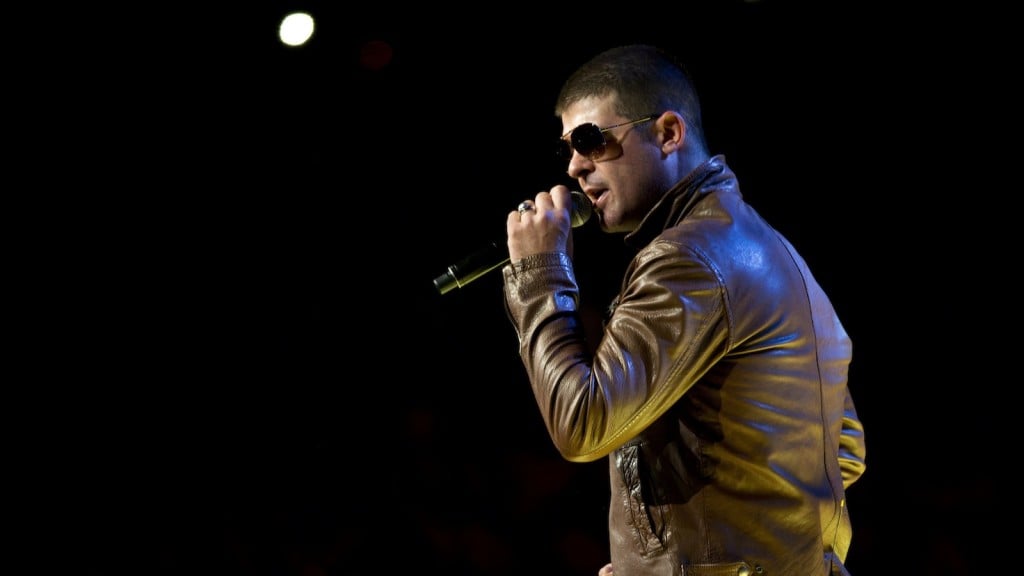

Robin Thicke performs on stage during the annual Wal-Mart Shareholders meeting in Fayetteville, Ark., Friday, June 6, 2014. The annual Wal-Mart shareholder’s meeting drew about 14,000 people, including its workers from around the globe. (AP Photo/Sarah Bentham)

Share

First off, no one has sympathy for Robin Thicke—probably not even Thicke himself. Not only did he grind with Miley Cyrus and unleash Paula on an unsuspecting world last year, but he also admitted to lying about co-writing his megahit, Blurred Lines, which yesterday was determined by a U.S. federal jury to have copied Marvin Gaye’s Got to Give It Up. And few will feel sorry for the song’s actual writer, Pharrell Williams, who’s gotten lucky enough in recent years that the US$7.4-million judgment won’t bring him down.

And yet, history suggests this ruling will have scary implications for all musicians. When Biz Markie, in 1991, was judged to have infringed copyright by sampling Gilbert O’Sullivan’s Alone Again (Naturally) without permission, the case curbed the creativity of the hip-hop and dance genres. Anarchic and psychedelic collages from Public Enemy’s It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back to A Tribe Called Quest’s Low End Theory gave way to watered-down hits like Puff Daddy’s I’ll Be Missing You, built on a Police riff its creator could afford to buy. The effect of the Blurred Lines verdict could be even worse.

Here, no sampling was involved; rather, Thicke and Williams were accused of interpolating musical elements. The Gayes’ lawyer, Richard Busch, closed his arguments by asserting, according to Billboard: “What it boils down to is: ‘Yes, we copied. Yes, we took it. Yes, we lied about it. Yes, we changed our story every time.’ . . . Are you going to believe Robin Thicke, who told us all he’s not an honest person?”

Certainly, it matters to Thicke’s ex-wife whether or not he was honest, but why should a jury care? We’re not talking about murder here. An artist’s intention may be nice to know, but it’s irrelevant. For instance, if I walk into a studio intending to rip off Marvin Gaye’s Sexual Healing and end up with something that sounds more like the Teletubbies’ theme song, should I be accused of copyright infringement? Or simply incompetence?

Furthermore, no one ever alleged that Blurred Lines incorporates any of the lyrics from Got to Give It Up, or the chord changes, or even wholesale melodies—the last two being why Sam Smith gave Tom Petty songwriting royalties for Stay With Me, after hearing I Won’t Back Down. The argument that Blurred Lines copied Got to Give It Up is based on what the Gaye team’s musicologist, Judith Finell, called a “constellation” of “eight similarities” between the songs.

Without delving into the more abstruse reasoning Finell supplies in her report, they include:

—Hook melodies that move from a scale’s fifth note to its sixth, and up to the root (so basic an idea as to be nearly meaningless, especially in pop, where many pentatonic melodies skip the seventh note anyway)

—A bass line that descends from the fifth note of a chord to the root. (This happens all the time—see, for instance, Girlfriend Is Better by Talking Heads.)

—The “splash” of a hi-hat on the second half of the fourth beat of the bar (a common device—try Bizarre Love Triangle by New Order)

—Keyboard chords on the offbeats, containing the third and fifth note of the scale (the entire genre of polka says hello, as does ska)

—The distinctive use of cowbell. (Many with a similar fever have written the same prescription.)

Arguably, some of these elements should have been immediately discounted, since the judge ruled that only the sheet music to Got to Give It Up was under copyright; Finell offers dubious grounds on which to base an argument of “copying.” If juries can be swayed with such logic, one might imagine an army of ambulance-chasing music lawyers glued to their radios, ready to sue the creators of the very next pop hit for, say, the use of a triangle on beat 3 of the second bar of the bridge. Computer programs could be deployed, akin to the Turn It In service that checks word strings in students’ essays for plagiarism—although there are a lot more words than there are musical notes, at least in our well-tempered Western system.

What’s more, the very idea of the homage—which Blurred Lines would seem to be, in its vibe (the theoretically un-copyrightable feel of a tune)—disappears when musicians become afraid even to reference the musicians who inspired them. It’s a fair bet Got to Give It Up racked up quite a few streams and downloads since Thicke mentioned it was one of his favourite songs in an interview with GQ. But after the Blurred Lines ruling, not only should one never meet one’s heroes; one shouldn’t even mention them.