The Hip & Me: Close encounters with the band

On the last night of the final tour, Canadians explain their love of a band and its legacy

Fans take their seats before Tragically Hip shirts outside the Air Canada Centre in Toronto. (Photograph by Nick Iwanyshyn)

Share

Dallas Green (City and Colour)

When I was a teenager, I used to work with my dad, going around to concerts and things like that. He worked for a company called Tropical Breeze. I would stand out in the middle of a crowd and sell all-natural fruit popsicles to people. There was a musical festival at Mosport racetrack in Ontario. I was starting to really get into guitar. The Cure had headlined one night, and the Tragically Hip headlined the other night. People were done buying popsicles, so I got to go watch the band play. I was young and impressionable. I don’t know if I was necessarily ready to believe that I could do something with my music, but that was when I was really soaking in a lot of live performances. I remember watching the Tragically Hip capture an entire field full of people. Little did I know that years later, I would ask Gord to sing one of my songs.

It was 2007. I sent him an email with a little demo attached, then he called me and just talked about the song [called “Sleeping Sickness”]. He agreed to do it. I was recording in Hamilton. He was in Kingston at his cottage with his family. He just drove up one morning in his station wagon. I asked him, “Do you want to write your own words?” He said, “No, I like what you wrote.”

I asked him about the cottage. He had been talking to one of his neighbours, who was an older man, about farming. The man said, “This is work that I can understand.” Gord used that to explain how important it is to find work that you’re able to understand. They were words of wisdom being passed along to him, and he passed them on to me.

Mark Zacharias

I’m from a small town outside Winnipeg. Playing college hockey in Mankato, which is outside of Minneapolis, all we did was listen to the Hip. We got the Americans listening to the Hip. And fortunately for us, we could watch the Hip at [the club] First Avenue in front of 1,500 people [in 2007]. So we’re going up there, and we saw them at the [Minneapolis] zoo. My buddy had on a Flin Flon Bombers T-shirt. He threw it on stage, and Gord grabbed it. So I’m sitting there at First Avenue I’ve got my Canadian stuff on, just like most Canadians. I’m having a blast. It’s about four songs in. It is so hot. I take my Canada shirt off. I lose one of my sandals. I’m just in a pair of shorts and one sandal. My shirt’s on. And I windmilled it, thinking, “Who knows? Maybe Gord will give it up to the Canadian fans.” Sure enough—I was sweating so hard I didn’t overhand it, I underhanded it—it hit him square, right in the head. And he got pissed off. He stopped the set. There I am with one sandal, no shirt, and I’m looking, and he points at me. He goes, “Get this guy out of here.” The only thing I could say was, “Sorry, Gord, I’m from Canada.” I think what he said was, “I don’t give a f–k where you’re from.”

The security guys are around me. I point at my hand. I go, “I’m the guy that did it.” I mean, to us that’s like hitting Wayne Gretzky in the head. I felt so stupid, and I’m looking for my sandal. I said, “Screw it. Screw the sandal. I’m going to walk out in shame.” I walked out of First Avenue. I made sure not to cause a commotion. I told the bouncers, “I’m kicking myself out.”

I wasn’t going to make a circus out of this. I was embarrassed. The Hip is everything to all of us. I walk out of the concert, and there I am. I had a wallet in my pocket. I got in a cab. I go home, and my wife goes, “It’s 10:30 at night, what are you doing home?” I told her the story. I was in shame. I got on the website, and then I emailed Gord. I said, “Hey, I’m the guy that screwed up and hit you, and it stopped the show. I apologize. I truly do.” I never heard anything back.

Four or five years ago, they come again, in October. All my same hockey buddies, they go to the Hip. I did a tie-down with my jacket. I took a tie-down with a hockey string to my belt loop. The big joke was that I can’t throw any shirts off, take any clothes off. I actually emailed the Hip again. I said, “Hey, Gord, I’m looking forward to your show. I’m the guy that hit you in the head. I put a tie-down on. I’m good to go. Have a safe concert.”

Heather Haynes

Paul Langlois and his family have a cottage on the lake where we live. If you like music and campfire, it’s pretty amazing. It’s a bit of a dream. There was one time when all the guys from the Hip were there. We have beautiful loons, and they gather in front of the Langlois cottage and sing. I always think that’s fascinating, they play in sync with their songs down there. Very Canadian. The families all have really great kids. They all work together at camp. They all stick together like a pack of wolves.

Each year there’s been a talent show, and the Olympics on the lake. There [are contests for] smallest splash and eating corn or chugging beer in a relay. Paul is in them all. He likes to swim and dive off the platform. I’m not sure if he does it for exercise, but he definitely does it for joy. He’s the master of the swan dive off the high platform. He soars with his long hair. Paul would always win that. That would be all grace.

Nadia Litz

I was 14, and I was a bit of an outsider. I went to a private school. I wore all black and brown lipstick. I wasn’t someone who was an obvious fan. I was into bands like the Cure and other alternative music. I was struck mostly by Gord and his performance style. The Hip was coming to Winnipeg where I lived. Everyone was going to that concert. Somehow his commitment to being this animal on stage spoke to a lot of people.

I don’t know why, but I thought he might like bourbon. I didn’t even know what bourbon was. To me, it was something that poets drink, and I thought of him as a poet. I wrote him a note on a card. I explained my love for one of their unreleased songs, “Get Back Again.” It was so naïve. They were playing at a stadium. That afternoon, my dad gave the note and the bourbon to someone who worked at the stadium and said, “Could you try to get it to the Tragically Hip?”

When the concert was three-quarters of the way through, I suddenly heard something, that they were dedicating this song to me. “This one’s for Nadia. Thanks for the bourbon.” I remember screaming. My best friend hoisted me on his shoulders, I was up for the whole song. They played “Get Back Again.” And [that was a song] they never played.

The popular kids from school were saying, “Was that you? How’d you do that?” In the hallways at school, there were a lot of high fives. Gord kind of made me feel like a prom queen.

Don Cherry

[For the music video of the Hip song “The Darkest One”], the Trailer Park Boys were stealing an engine out of a car for Gord and the boys [in exchange] for some chicken. So I delivered the chicken and he paid me in two-dollar bills. Then his cats ate the chicken, so I had to come back with more chicken. Then I get into a real tussle with the Trailer Park Boys. We were supposed to get into an argument. You know the guy who’s always smoking and has a rum and coke in his hand all the time? I knocked a cigarette out of his mouth so he pushed me, I pushed him and he knocked my hat off. It was really funny.

It was really cold that day, too. Gord was great. When [the video shoot] was over, he says, “Don, are you going back to your truck?” I was going home. He said, “I really want to apologize, Don.”

I’m thinking, what the heck is he apologizing for? What happened was: I don’t [normally] go to awards banquets, but he was going for an award—CBC something, I forget—and I thought if Gordie’s going to do it, I’ll go too.

But he backed out—I think his wife was sick or something. It bothered him for two years that he saw me up there [on TV] but he had never followed through. I had forgotten all about it, but that’s the kind of guy he was.

My brother used to see them in Kingston when they used to play road hockey. He’d go by and wave to them. They were just kids back then.

I’ve always loved their show. I like how he’s always talking about Canadians; he reminds me of Stompin’ Tom. Gordie never forgot Kingston—or his Canadian roots.

Derek Roy

It was ’07, and we were in a playoffs run. The Hip was playing in Buffalo, and we were playing in Ottawa against the Senators. One of my friends went to the concert. He told me the story about Gord swapping my name while he was singing a song with lyrics about Bobby Orr. I think it’s because all the Sabres fans in the audience were excited about us being in the playoffs and could potentially win the Stanley Cup. It’s kind of cool how he put me in the same category as Bobby Orr, this guy who’s a legend, a Hall of Famer, one of the most respected hockey players of all time. To hear him swap the name for your name, that’s kind of cool. The fans liked it at that time and my friends did. Those are ageless rock songs that will last forever.

Jeff Montgomery

I’m Paul’s friend, and I never really called myself a bass player. We always had chats about the Hip and what life on the road is like. I was always sort of curious. He was able to provide that experience for me by saying, “You’re in the band, and we’re going on the road.” The bus was from Florida. The heater wasn’t always the best. The windows would ice up as we were going through the Rockies.

There was a very proud moment. We were in Moncton, N.B., and one of Paul’s songs was used in the introduction to Hockey Night in Canada. Everybody on the tour bus, we were huddled together in a bar. You could see how proud we all were.

We always ended up having a drink before the show—one of the favourites was vodka and red bull. It became automatic. Nobody really had to ask for it. We’d have a light meal, just so any nerves in your tummy didn’t turn into something bigger.

Hank Connell

All the boys were in my Grade 10 science class. Johnny Fay would be behind Gord Sinclair. They were all in the right hand corner of the health class I taught, near the back. I was kind of innovative. We used dogfish sharks for teaching primary anatomy. They seemed to enjoy it. They’d say, “Hey, are we going to get the sharks out today?” I enjoyed those boys because they knew when to sit and be quiet and when to be involved in a floor hockey game. I also taught them in phys ed. I coached Gord in football. One game, I was standing on the sidelines close to half-time. He says, “Coach, we gotta change the name of this team.” I said, “What do you mean? The Blue Bears is what we’ve always been called.” He said, “No, you’ve gotta call us the Bad News Bears. Look at the score.”

The Trailer Park Boys

Robb Wells: There was one night where we were shooting, and a lightning storm was coming, and it was just incredible. They were improvising a song.

We used to shoot in a park that we owned that was gated. We used to have these big parties on Friday nights after wrap. Alex Lifeson [of Rush] and Gord were there. This night unfolded with a jam. It was so dangerous, it’s unbelievable. There was literally lightning striking all around us. Everyone was standing in about an inch of water. I remember looking down and seeing the power bar that my amp was plugged into floating in a puddle, but I didn’t want to stop, so I was like “Nah, I probably won’t get electrocuted.”

Mike Smith: There was a movie about the Canada-Russia hockey series a few years ago, and Gord auditioned. We auditioned for it too. We were somewhere in New Brunswick. We were in a hotel room. We were pretty banged up. We were watching that [Discovery Channel] show How It’s Made, with no volume on the TV. We would guess what was being made. It’d start with pieces of string coming off the assembly line, and we would just shout out silly things . . . I think Gord said “Doughnuts!” at one point. That was another surreal night, just getting to see how Gord’s mind works.

Robb Wells: There’s one story where we were shooting for an episode. For part of the shoot, we had to be towed behind this tow truck. It was freezing cold. We were in a car with no windows. It was four o’clock in the morning. It was just the four of us in the car, so we spent quite a long time freezing our asses off. Gord turned to us. He said something like, “We’re freezing, we’re tired, whizzing down this highway, getting blasted with cold air, but you know, life is pretty good guys.”

Chris Bowden

I volunteer at the Hillside Festival [in Guelph, Ont.]. They decided as a fundraiser to have the Tragically Hip play and I sold beer tickets. At Guelph Lake Conservation Area, there’s a cement stage that sits there and basically just gets used at the Hillside Festival. We got done selling the tickets and were told to go behind some trailers behind the stage. That only bit of the concert we saw was from behind a translucent backdrop on the stage, and we just got to watch the encores from there. When they were done, they noticed we were just out in the middle of a field. Sure enough, the band was just coming straight toward us. We were cheering and thanking them and saying, “That was a great show.’”There were about seven of us who were all just counting cash. The only person who stopped was Gord. He was dripping with sweat. He said, “How are you guys this evening? What was your role here tonight? We’re guessing that since you’re back here that you weren’t able to watch the band.” We said we were selling beer tickets. He said, “It’s a darn good Canadian thing that you’re doing here. Just do me a favour. Just wait here.” So we all sat there and waited. Sure enough, 15 or 20 minutes later, there’s Gord Downie with the rest of the band. The rest of the band had a VIP tent. Gord said, “Come over to the VIP tent and have a beer with us.” We heard we didn’t have the right wristband [for admittance to the tent]. He said, “Oh, let me have 10 minutes in there, and you just show up at the tent.” We waited about 10 minutes. The person at security said, “No you can’t come in.” We yelled out for Gord, and he said, “They’re with us.”

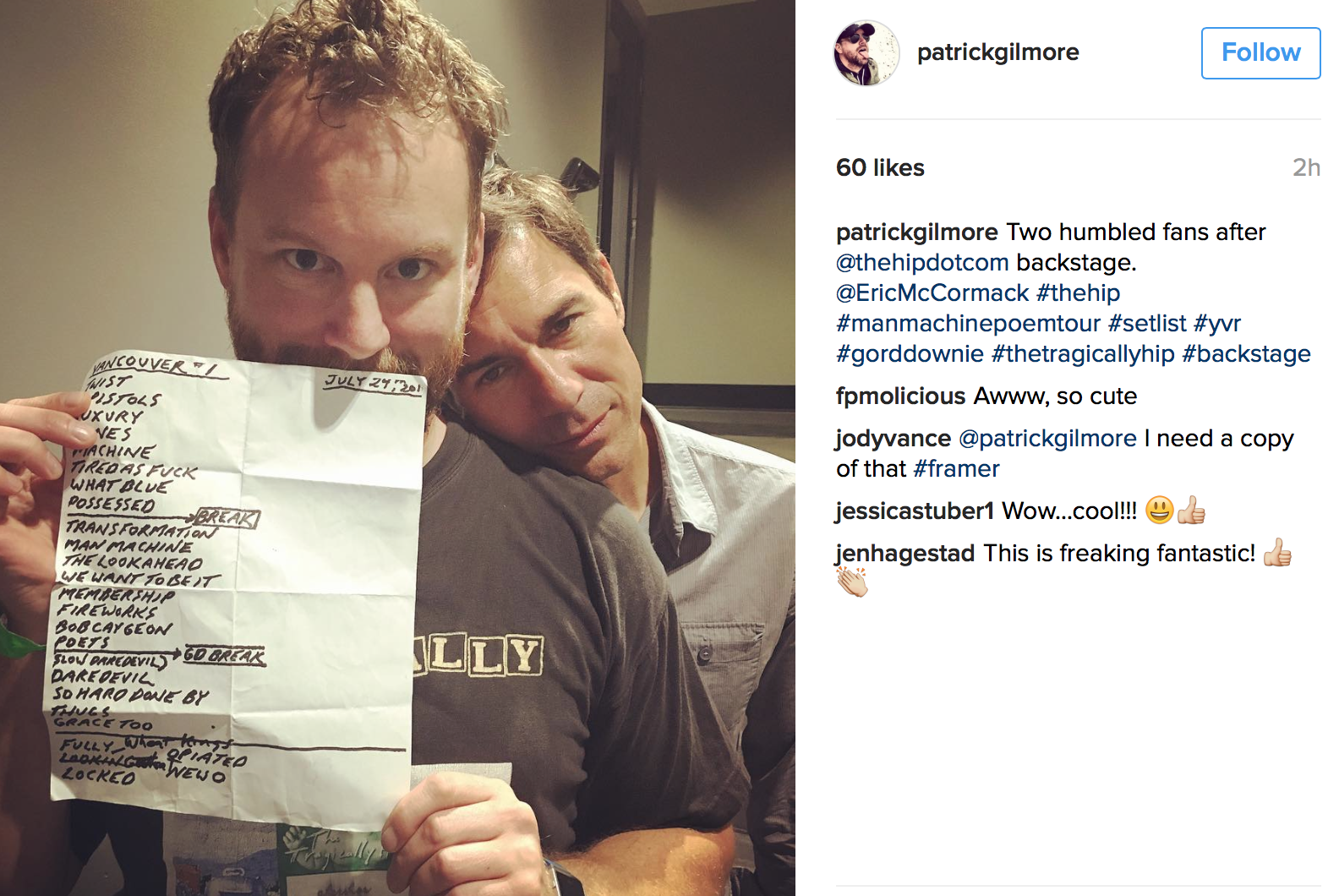

Patrick Gilmore

The first Victoria show was pretty emotional. This was the last time I was ever going to see them live. Second row. Gord’s always the centre of attention. What was beautiful to watch was often Gord would forget his lyric—not often, but more than I remember him screwing up a lyric before. The band was there with their shorthand, their silent communication. If he was off a beat, the band would kind of give a little look to each other and then skip a beat just to get in rhythm with Gord. The band coming together just to make sure he gets that perfect game.

The really poignant part came when they finished their first set, before the encores. The band kind of dissolved into the background, and Gord was there. He went around with his hand on his heart and just nodded and said thank you to everybody. The best moment for me was that first goodbye where he came around to my side of the stage, and I had my hand up in the air, and I got his attention, and I pounded my chest, and I mouthed, “Thank you.” He looked me right in the eyes, and he kind of smiled and nodded. That is so small, but that is all I ever wanted to do, was to say thank you because they were the soundtrack of more than half my life.

Brent Butt

It started with just an idea. It’s in season two [of Corner Gas]. The episode is called “Rock On,” and the episode is about Brent and Wanda and Hank deciding to get their old high school band back together again. When we were writing the script, the idea was that they needed a place to practise, and they were going to practise in Brent’s garage. I just thought of [writing]: “Aren’t you already letting some local kids practise in your garage?” He’s like, “Yeah, we can give them the boot.” And then it was the Tragically Hip. Once we wrote that joke down, we wondered if we could actually get the Tragically Hip to come on and play, so we just reached out, and it just happened to be at a time when it worked in their schedule. We put them on a plane and winged them out to Regina. We thought it was kind of a long shot. They were into the idea of it.

One of the things that really sticks out in my mind is just how many crew members we seemed to have on that particular day. I think every crew member brought five friends and family to the studio, and everyone was hanging around like they had work to do because they just all wanted to be in the studio where the Hip were going to be playing and recording. I remember showing up and going, “Come on, this is five times as many crew as we have.” It was like a private concert.

We recorded the scene with the Hip first thing in the morning—seven in the morning—and I could not believe how they were just belting it out. They were playing as though they were in an arena full of 20,000 people. I think they only have one speed when they perform, and it’s full on. They were singing “It Can’t Be Nashville Every Night,” and Gord was belting it, like I could see the veins in his neck. I was like, “Man, they’re giving 100 per cent here, at seven in the morning.”

I wasn’t sure how they’d like the line where my character kicks them out of the garage—“You gotta scram.” Then Gord says, “Come on, Brent. Me and the boys are working out the lyrics.” And I said, “Don’t tell me what the poets are doing. Just end script.” That’s a lyric to one of their songs. They thought that was cool.

They’re such giant cultural icons. They’re just woven into the backrop of Canadiana from the mid-’80s on. But they were such regular guys hanging out.

When I hosted the Juno Awards, that year they were given a big iconic award. They came out and performed. They killed and brought the house down. When they finished, they left to come off stage. I was standing in the wings there, and they just walked past and went, “Oh hi, Brent,” just like we had bumped into each other at the corner store.

Amy Pike

I’m going to guess it was 1987. What I remember vividly is that this was more of a coffeehouse bar. It wasn’t the big, beer-spilled-all-over-the-floor kind of dance bar. It was Roosters at the time. Probably only about 150 people could fit in there. Sitting at the table, playing euchre of course, because that’s the only thing you would do in an Ontario college bar. It was not a late evening. It was probably early, suppertime-ish is my bet because it was light out. I remember distinctly listening to this band as we were playing cards and saying to each other, “I wish there wasn’t a band playing because I can’t hear you very well.” You know that moment when you’re thinking, “This is kind of annoying.” It seemed like a weird band for an afternoon—so loud and so much energy in a bar that wasn’t that filled up with people. I can vaguely remember us saying something like, “Could they turn down the volume?” Not to the band itself, but a waitress or something along those lines.

But within one or two songs, we all were just standing there with the cards in our hands thinking, “Okay, this is different. This is not a small-town act. These guys are going to go somewhere.”

Fast forward 20 years, and Paul Langlois bought a cottage 10 cottages down the road from our family cottage on the Rideau system. My parents who canoe by their dock have a chance to hear the Hip jamming on the dock late at night, and love every second of it of course. It’s obviously loud. It travels across the lake. I’ll get an email saying, “We heard the boys playing last night. We paddled out just so we could listen to them.”

My parents emailed Paul one day. “Listen, my daughter lives in San Diego, and she heard you’re playing at the Belly Up Theatre, which is a really funky beach bar. Is there any way you can get her backstage passes?” And he did. So my fellow Canadian friends here and my husband and I, we went to probably the favourite of all the shows I’ve ever seen. It was so intimate. It was so ridiculous. It was 600 screaming Canadians, all dressed in red and jumping up and down, and afterward we went backstage and got to meet everyone except for Gord.

The Canadianness of it all is that I was sitting there backstage afterward with this sweaty band, and he and I were discussing the state of the dirt road leading into our cottages. It was one of those surreal moments. We were saying, “We should really do something about that one corner where it’s really hard to see.” My friends and my husband were saying, “This is really Canadian.”