A Canadian magic trick: wages that rise even if productivity doesn’t

An Econowatch special report on productivity (part three)

Share

If you spend any time reading about the Canadian economy, you have inevitably come across the Great Canadian Productivity Puzzle. Canada’s productivity is much lower than that of other countries, and we don’t really know why. Neither do we seem to be able to fix the problem. Policymakers have used every trick in the book to try to boost productivity, but the results have disappointed. Productivity growth matters because it drives up our purchasing power: if it lags, so will our standard of living. And yet—here’s where things get interesting—Canadians are far better off than one would tell looking at our dismal productivity performance over the past 20 years. How did we do it? In this six-part special report, Maclean’s in-house economist Stephen Gordon investigates the mystery. (With a contribution from Econowatch editor Erica Alini.)

Click here to see what’s coming up next and view past posts.

The trick

In part one of this series, I made the point that income growth is driven by productivity. In part two, I noted that Canadian productivity growth has stagnated since at least 2002. You’d think Canadian incomes would also have stagnated, but they haven’t. There’s another piece that has to be added to the productivity-income puzzle.

First, though, a quick recap.

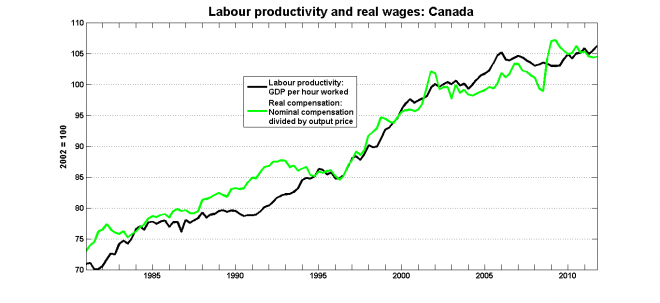

From part one: wages track productivity.

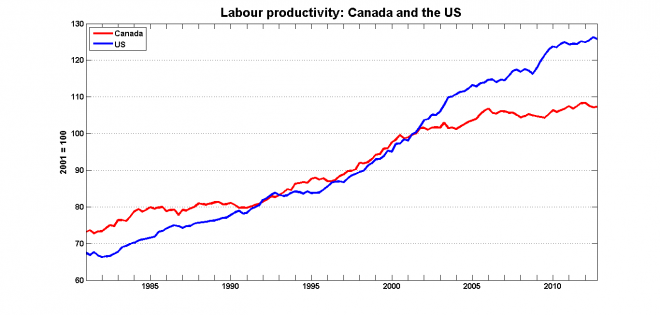

From part two, Canadian labour productivity growth has been lagging that in the U.S.

From part two, Canadian labour productivity growth has been lagging that in the U.S.

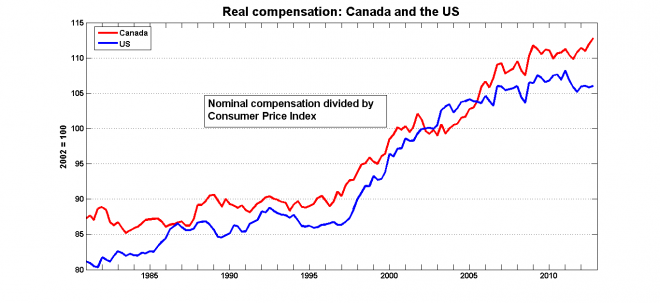

But look how the real purchasing power of wages have evolved in the two countries.

But look how the real purchasing power of wages have evolved in the two countries.

Even though workers’ productivity has grown more slowly in Canada, our inflation-adjusted earnings have grown faster than in the U.S. How is that possible if wages track productivity? The answer is international trade.

Even though workers’ productivity has grown more slowly in Canada, our inflation-adjusted earnings have grown faster than in the U.S. How is that possible if wages track productivity? The answer is international trade.

It all goes back to commodity prices

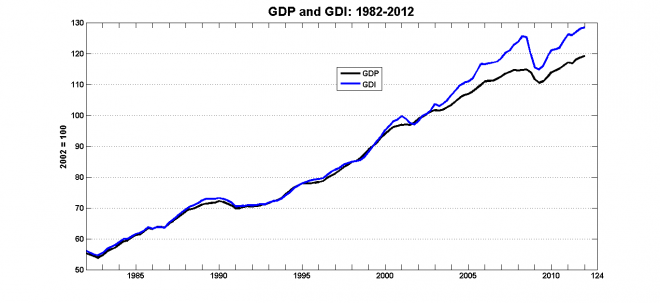

If the price of a country’s exports rises relative to the price of the goods and services it imports, then purchasing power will improve, even if productivity levels stay the same. This shows up in the national accounts as a divergence between GDP, which is a measure of production, and Gross Domestic Income, which tracks aggregate income. (For a more detailed explanation of the distinction, see here. It involves beer and pizza.)

The reason why GDI started trending above GDP is the same reason wages have been growing faster than productivity: the surge of commodity prices, and of oil prices in particular, since 2002.

The reason why GDI started trending above GDP is the same reason wages have been growing faster than productivity: the surge of commodity prices, and of oil prices in particular, since 2002.

Another way of saying this is to look at producer and consumer prices. Rising commodity prices and international trade also put a wedge between producers’ prices (what firms receive when they sell the goods and services they produce—this is the price firms use to calculate the real wage that tracks productivity) and consumer prices (what consumers pay to buy stuff—the lower they are, the greater workers’ purchasing power). The reason why workers in Canada fared slightly better than in the U.S. is that producer prices here grew more rapidly than consumer prices, while the opposite was going on south of the border. Canadians’ buying power increased because the prices of the things we were selling grew faster than the prices of the things we were buying.

Yes, high oil prices are a good thing

Many commentators go on to conclude that the higher incomes generated by high commodity prices have given Canadians a temporary reprieve from the problem of low productivity growth. Jeffrey Simpson’s take on this is typical of this line of thought:

“Canadians are so damn lucky. We just dig and pump and cut and ship, and we never seem to run out. We just hope commodities prices remain high.

All those resources can be a fool’s game. Pumping and digging and cutting can keep the country comfortable, but they do little to address the country’s biggest challenge – a sagging competitive position. All those natural resources soak up capital; they usually don’t require much innovation or processing…

The old model of exploiting natural resources and shipping most of them (and everything else) to the United States will certainly keep Canada comfortable. But increasingly it won’t make Canada more productive at a time when the population is aging and immigration isn’t working. Without better productivity, forget real income growth. Without it, a comfortable stagnation.”

And here is Dan Gardner making a similar point along with a quote from Don Drummond:

“In June, when the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) released its latest report on Canada, it hit on a theme that is depressingly familiar to economists: Canada’s productivity growth is awful. And getting worse. ‘Canada’s overall productivity has actually fallen since 2002,’ the report noted, ‘while it has grown by about 30 per cent over the past 20 years in the United States.’ On a chart, the lines tracing Canadian and American productivity are essentially equal in the late 1980s but slowly diverge in the 1990s and then, in the last decade, an enormous gap opens.

If we don’t close that gap, our prosperity will slip away when the commodity boom goes. And the commodity boom will go. They all do.

So how do we improve productivity? ‘Twenty years ago we created a laundry list of the things we needed to change in the policy front and productivity would blossom,’ says Don Drummond, one of the country’s leading economists.

‘And you know, we changed most of them but productivity didn’t blossom.’ ”

I think these narratives have things backwards. In the next post, I will argue that the standard metric of productivity growth hasn’t slowed because of any particular failure of Canadian firms or Canadian policy—although there’s always room for improvement. Instead, the problem is how we measure productivity.

****

- Part three: A Canadian magic trick: wages that rise even if productivity doesn’t