What’s really behind food price hikes

Andrew Hepburn considers the influence of biofuel subsidies and financial speculators

Share

This is the last installment of a three-part series. In part one, Andrew Hepburn wondered whether rising demand from China and India can really be blamed for food price hikes. In part two, he delved into the supply-side of things, looking at food stocks. Here, he turns to U.S. biofuel subsidies and financial speculators.

From oil prices to rising consumption in China and India, the explanations tossed around to make sense of the sky-high food prices of recent years are many.

Yaneer Bar-Yam dismisses most of them.

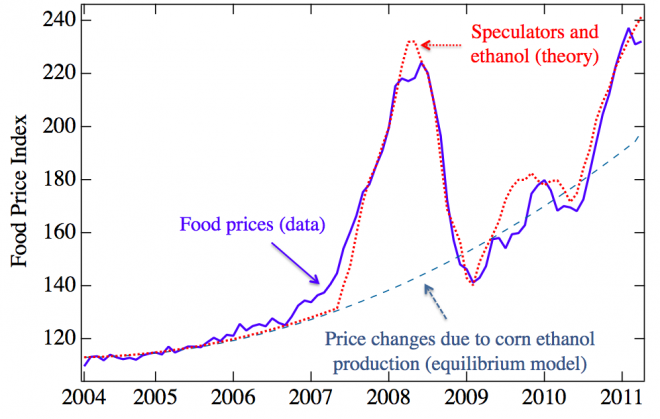

He and his team of researchers at the New England Complex Systems Institute have mathematically modelled a well-known basket of food prices—the Food and Agriculture Organization’s Food Price Index—and concluded that two causes are behind expensive food: corn ethanol and financial speculation.

According to the NECSI model, shown below, corn ethanol production explains the gradual trend of higher food prices, while investor participation in agricultural commodity markets is responsible for the sharp spikes and crashes, such as the one seen in 2007/2008 boom-and-bust cycle.

Here’s how Bar-Yam explains his group’s methodology to me:

Here’s how Bar-Yam explains his group’s methodology to me:

“We picked the biggest one of the fundamental factors, which is the ethanol and threw everything else out … then we added the mathematical model of speculation. And the only other thing we did is we said speculators will move their money between markets, so they’re should be a shifting between commodities and stocks and bonds … You add that in and the prices match very, very precisely.”

Indeed, only the massive drought in the U.S. midwest this past summer was enough to meaningfully affect NECSI’s model for agricultural commodity prices going back to 2004.

Food as fuel

If you think corn is overwhelmingly used as food, you’re living in the past. As NECSI notes, “Only a small fraction of the production of corn before 2000, corn ethanol consumed a remarkable 40 per cent of U.S. corn crops in 2011.” The shift, they say, was “promoted by U.S. government subsidies based upon the objective of energy independence and advocacy by industry groups.”

In particular, under a 2007 U.S. law, the so-called Renewable Fuels Standard stipulates that ethanol must comprise 9 per cent of fuel companies’ gasoline pools. Ethanol is used as an additive in gasoline, helping to reduce harmful emissions. Corn is the main “feedstock” for the production of ethanol in the U.S. Not surprisingly, the use of food as fuel as sparked calls for the U.S. government to withdraw the ethanol mandate given high food prices.

It’s important to note that what happens to corn prices affects other food commodities as well. As NECSI explains, “Corn serves a wide variety of purposes in the food supply system and therefore has impact across the food market. Corn prices also affect the price of other crops due to substitutability at the consumer end and competition for land at the production end.”

For all the disagreement about other possible causes of food price hikes, there seems to be more of a consensus that ethanol production has played a sizable role. In fact, a leaked report in 2008 by a World Bank economist argued that biofuels accounted for 75 per cent of the increase in U.S. grain prices up until late 2007.

Are speculators also fuelling price-hikes?

The question of whether speculators can influence commodity prices by purchasing futures contracts is the subject of intense academic debate. Many people, notably Paul Krugman, dismiss the role of investors in pushing up everything from crude oil to wheat prices.

These critics question whether what happens in the futures market can affect “spot” prices (i.e. the price of purchasing the physical commodity for immediate delivery). Unless higher futures prices induce people to hoard commodities now in order to sell them later, experts like Krugman don’t believe speculation has an impact.

Other, such as Prof. Stefan Tangermann of the University of Gottingen, note that futures markets are in some respects unlimited compared to the physical market. So if speculators are willing to pay unjustifiably high prices, knowledgeable players will sell as much as possible to them, ultimately driving the market back down.

NECSI found a strong connection between the paper market and the physical market for food. Their research showed that granaries set their prices for physical grains (i.e. the “spot” price) using the futures market price as a reference point. Futures markets, according to NECSI’s work ,are what drives the prices of everyday staples.

This is not to say that supply and demand don’t matter; Bar-Yam’s team believes that speculator-driven prices ultimately push the market into a large surplus, causing investors to exit their bets en masse as they see inventories rising—gravity can only be defied for so long.

Time for smarter policies and stricter rules

With two culrprits identified, NECSI suggests two straightforward solutions. First, “a significant decrease in the conversion of corn to ethanol.” Second, stricter position limits in commodity markets to prevent speculators from distorting prices. The deregulation of commodity markets of recent years, they argue, needs to be reversed.

“One has to step back and now say, What do we really want the world to look like? We have the power to change what the world looks like. If we can figure out where we want to go, our policies can reflect it.”

–

Andrew Hepburn is a former hedge fund analyst. He’s a commodities bear and a keen observer of financial speculators. For Maclean’s he blogs about the economy and financial markets.