BlackBerry blues

The once-mighty RIM is fighting for its life—while the Canadian tech sector is still suffering from the loss of Nortel

Share

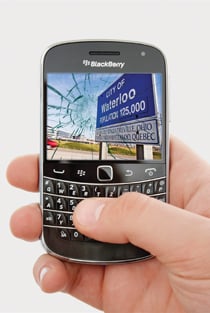

To get a sense of how deeply intertwined the Canadian identity has become with the BlackBerry, this country’s most famous modern-day invention, pick up a copy of the study guide issued by the federal government to help new immigrants prepare for their citizenship test. There, among the handful of inventors whose work is so critical to the country’s history that their names should be memorized—Alexander Graham Bell, snowmobile inventor Joseph Bombardier, and Wilder Penfield, the McGill surgeon who discovered epilepsy—are Mike Lazaridis and Jim Balsillie, the co-founders of Research In Motion.

The company’s smartphone revolutionized the global mobile industry and put both Canada and its hometown of Waterloo, Ont., on the map. RIM was the kind of rags-to-riches success story so rare in Canadian business, a firm that stayed loyal to its Canadian roots and steadfastly refused to move its headquarters to the United States. Its founders poured millions into research institutes and think tanks that drew the likes of Stephen Hawking.

All of which has made the decline of Canada’s largest technology company, and its biggest private research and development spender, particularly painful to watch. Over the past two years, RIM’s share price has plunged nearly 90 per cent, at one point this month dropping below $11 from its high of $148 in 2008. In March, RIM said it would stop giving out financial forecasts, after posting its first quarterly loss since 2005. Its share of the global smartphone market has steadily eroded (now estimated to be less than seven per cent) thanks to aggressive competition from Apple, Google and Samsung.

Canadians held on longer, even as consumers south of the border ditched their BlackBerrys for iPhones in stunning numbers. Up until this year, BlackBerry remained the top smartphone among Canadian consumers. But even hometown loyalty has its limits. This year, according to one estimate, RIM’s share of the Canadian smartphone market finally slipped below that of Apple. While more Canadians now own smartphones, the number with BlackBerries fell from 42 per cent to 33 per cent last year, according to J.D. Power and Associates.

In a second blow, the company fell from its perch as Canada’s most valuable tech company. It now sits below Montreal’s Valeant Pharmaceuticals, makers of COLD-FX, according to a ranking by Cantech Letter, a publication that tracks public Canadian tech companies. Thanks to a merger with Biovail in 2010, Valeant is worth $16 billion to RIM’s $6 billion. (Last spring, RIM was worth $30 billion.) Canadian politicians, who frequently touted the company as the shining star of Canadian innovation, have also dampened their enthusiasm. Federal Finance Minister Jim Flaherty recently hinted that Canada might not seek to block a much-rumoured foreign takeover of RIM, as it did in 2010 with Saskatchewan’s Potash Corp., declaring that the company’s shareholders “will be the masters of their own destiny.”

That has left investors and analysts wondering what life in the Canadian tech industry would look like without RIM as we’ve come to know it. A rousing comeback appears increasingly unlikely given the company’s ongoing woes and the lacklustre response to its BlackBerry10. It’s not impossible that the company will keep suffering until it folds or tries to re-establish itself as a niche player in the business world by playing on its reputation for security. More likely, analysts say, is that the company will be sold to a foreign competitor seeking its portfolio of patents and sizable cash reserves.

“They were the Cinderella story for a long time,” says Queen’s University business professor John Pliniussen. “All the wealth that accumulated to the shareholders and to the employees and to the Waterloo Region and to the spinoff companies and all the philanthropy. They were the biggest light on the candle in technology for a long time. Now they’re sort of an embarrassment.”

So what will Canada’s tech sector look like under these sorts of scenarios? RIM’s rise from a company that made email-enabled pagers to one whose “Crackberrys” were the must-have toy of executives helped raise the stature of all tech companies in Canada.

RIM remains Canada’s largest private spender for research and development. It spent $1.6 billion in the last fiscal year, more than IBM, Magna and Bombardier combined and up more than 50 per cent from what it spent in 2008, according to Re$erch Infosource. The company accounted for the bulk of Canada’s growth in corporate R & D spending in 2010; without it, spending declined 11 per cent. (The country is already a laggard within the OECD, trailing the likes of Slovenia and Belgium.)

But ask Canadian tech watchers about RIM today and they often bring up another company that once drove investment in Canadian technology, but more recently has accounted for the largest drop in the country’s corporate R & D spending: Nortel.

Nortel was felled by a fraud scandal currently working its way through the courts. Its collapse, which ultimately pushed it into bankruptcy in 2009, saw billions’ worth of Canadian-made technology sold to foreign interests. RIM secured $4.5 billion worth of Nortel patents in partnership with other foreign-owned companies, largely by arguing that Canadian intellectual property should stay within Canadian borders. That, too, is now at risk with talk of a foreign takeover of RIM.

RIM certainly isn’t facing Nortel-style fraud allegations. But foreign investors have been reacting to what Paul Cataford, a technology finance expert with Espresso Capital Partners, says are RIM’s own “governance challenges.” They include fines from security regulators after executives were found to have backdated stock options and, more importantly, concerns over how RIM’s board of directors didn’t stop the company’s share price from plummeting. The fate of both companies has also left a lingering feeling that maybe Canadian tech companies can only grow so big, so fast, before they begin to crumble. “If you’re a U.S. institutional investor in a Canadian tech company, do you say, ‘We ought to apply the RIM governance discount against all tech companies?’ ” Cataford says.

Canadian tech stocks have been lagging in recent years thanks in part to investors flocking instead to the country’s booming commodities sector. Tech companies have often traded at a discount to their U.S. counterparts since investors south of the border tend to favour their own. But as RIM’s fortunes rose, so too did the cachet of other Canadian tech start-ups. “People tend to perceive these companies as fighting a little bit above their weight class because Canada has such a strong reputation in the tech sector as a result of the successes of RIM and others,” Cataford says. “That’s good to see, but when these things fail, it takes us all down a notch.”

RIM’s ongoing woes have also been an aggravating factor in a bear market that has discouraged Canadian tech companies from going public, says Nick Waddell, editor of Cantech Letter. In 2011, just one Canadian tech company went public on the TSX (software firm NexJ), according to a survey by PriceWaterhouse Coopers. “Up until 2008, a banker trying to take a tech company public could say, ‘Look at the valuation that RIM is getting,’ ” Waddell says. “They can’t really do that anymore.”

The gloom hanging over RIM’s stock has spread to other major Canadian suppliers like Celestica. The Toronto electronics manufacturer counts RIM as one of its biggest clients and saw its share price clobbered last year, despite rising earnings, as investors feared fallout from its exposure to RIM.

If RIM dies it would be a huge blow to the Canadian tech industry, but hardly one that would come as a surprise, says Pliniussen, the Queen’s professor. “There will be job losses; there will be turnover,” he says. “I’m sure everyone who does business with RIM, although they have their fingers crossed, they have a backup plan.”

Perhaps the most significant implications for RIM’s decline have been within the company’s hometown of Waterloo, where RIM employs a sizable portion of its 16,000-person workforce. Co-founders Balsillie and Lazaridis are fixtures in the community, donating hundreds of millions of dollars of their vast personal fortunes to community foundations and pet causes such as the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics, the Institute for Quantum Computing and the Centre for International Governance and Innovation.

The company’s struggles have proven a wake-up call to the legions of entrepreneurs drawn to the region with dreams of becoming the next Research In Motion, says Iain Klugman, head of the region’s start-up incubator, Communitech. “What this has really reminded us is that the technology business is a very different business than anything else. It’s what makes people love it,” he says. “But things can change really quickly and it’s incredibly competitive. This couldn’t happen in the banking industry. People tend to think that so-and-so is ‘blue chip.’ If they’re in the technology industry, they ain’t blue chip.”

Among the companies spawned by RIM’s presence in Waterloo is Polar Mobile, a growing young outfit that makes mobile applications for newspapers and magazines, including GQ, Vogue and the Hockey News (along with Maclean’s). Polar was started in 2008 by a group of University of Waterloo graduates, including some former RIM employees, who set up shop next to RIM and designed products mainly for the BlackBerry. “In school, you were very much influenced by it. Half your friends worked at RIM and had BlackBerry devices,” says founder and CEO Kunal Gupta, a UW computer science grad. “It was a bubble where everybody had a BlackBerry. We felt ahead of our time.”

Polar moved to Toronto, where it now employs about 50 people. Its 1,200 apps, for iPhones, Androids and BlackBerrys, have been downloaded 11 million times. These days, however, Gupta says his company is holding off on designing apps for the upcoming BlackBerry 10. “We’re going to wait and see based on market demand for the device.”

If anything, RIM may be a victim of its own success when it comes to its close association with Waterloo and its universities. The University of Waterloo is now ranked among the top North American schools for computer science. It caught the eye of Bill Gates, who declared it one of the top recruiting grounds for Microsoft. Google opened a development office there in 2010 and Facebook has been rumoured to be contemplating the same.

These days, students complain about RIM’s layers of bureaucracy and a middle management that stifles innovation. Several say the company still offers good jobs for grads looking for a stable 9-to-5 career, but is no longer a firm with its finger on the pulse of future technology. “RIM has a reputation on campus of being mired in mediocre management and HR,” says Matthew McPherrin, a fourth-year computer science student who has worked at Mozilla and Amazon. Most of his top classmates applied to Google, Microsoft, Facebook and Twitter “or some hot San Francisco start-up,” he says. “Tales of cubicle farms, layoffs and fear of the future don’t inspire in the same way that the songs of start-ups looking to change the landscape of technology do.”

RIM is now seen among many students as a company “left to subsist on competent but unremarkable graduates that have, in many cases, been passed over by every single one of their major competitors,” says Anthony Brennan, who has studied computer science in Waterloo since 2006. All that means the community’s brightest talent is now heading to companies based mainly in the U.S.

Still, Waterloo’s fortunes are hardly dependent on RIM, says Waddell. The community of less than 100,000 was able to absorb RIM’s 2,000 layoffs last year. (Unemployment in the region actually went down.) Klugman says three tech start-ups walk through the doors at Communitech every day, and 300 have launched in Waterloo in the past year. “The interesting thing about the people in this community is they look at tough times and they don’t go, ‘Oh my gosh, the sky is falling.’ They go, ‘Hey it’s time for us to pull ourselves up by our bootstraps,’ ” he says. “We’re up for a fight. Yeah, it’s a tough period for RIM right now, but I don’t see any reason why anyone should be giving up on this company.”

Cantech’s Waddell points to other emerging tech powerhouses based in Waterloo, including enterprise software giant Open Text, logistics firm Descartes Systems, networking equipment company Sandvine and e-learning outfit Desire2Learn, as companies that can step in to become the region’s next RIM-like success story. “My feeling is we don’t need the Canadian tech sector to be one giant anymore,” he says. “We need 50 to 100 smaller companies and that’s what I think is emerging out of there.”

Still, he adds: “On a purely psychological basis, it feels like another giant has come down.”