Canada’s fatal attraction to debt

Why we can’t stop living on credit

Peter Mccabe/CP

Share

“Canadians like to see themselves as the Scots of North America,” theatre critic Ronald Bryden wrote back in 1984, “canny, sober, frugal folk of superior education who by quietly terrible Calvinist virtue will inherit the 21st century.”

Sorry, which country was that again? Like looking at a younger picture of yourself and straining to see the resemblance, the Canada Bryden described is barely recognizable today. It’s probably true Canadians were never as frugal as we liked to think we were. But with household debt on the march to $2 trillion, a savings rate a fraction of what it was 30 years ago, and waves of warnings from international banks and Nobel-winning economists about our debt-fuelled housing market, any pretense to prudence has long since been banished. If a scriptwriter were to pen the tale of our transformation into giddy spendthrifts, the working title would surely be: How Canadians stopped worrying and learned to love the debt bomb.

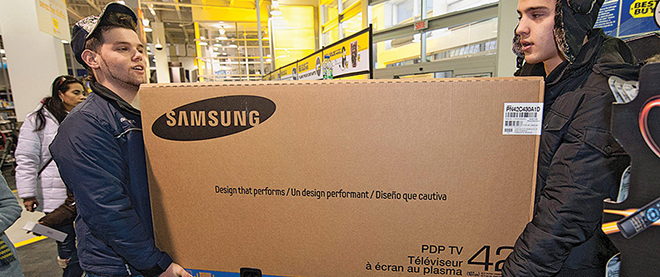

You’ll have heard these warnings before, usually in a scolding tone. But what we are seeing is a fundamental shift in our attitudes toward living on credit, one that’s not really that illogical, given money is essentially free. An era of low rates has desensitized borrowers to the risks inherent in carrying too much debt. A whole generation of young Canadians has come of age in an era when no bungalow, renovated kitchen cabinets or TV is ever truly out of reach.

Last year, economist Paul Masson, in a report for the C.D. Howe Institute, took the Bank of Canada to task for keeping rates so low for so long, for the very reason that it’s inducing people to do risky things. Masson’s report included an example of why low rates are so seductive. Assume a couple earns $100,000 and want a five-year mortgage amortized over 25 years. Lenders typically insist young households devote no more than 32 per cent of their income to housing costs, like mortgage payments, property taxes and to keep the heat and lights on. If mortgage rates were 10 per cent—a figure that sounds shockingly high, but is roughly what the average five-year rate has been since the 1970s—they’d only be able to borrow $200,000. But with mortgage rates available for three per cent at one point last year, our fearless homebuyers could borrow $300,000. What’s another hundred grand?

A back of the napkin calculation shows the monthly payment on that mortgage at three per cent, $1,420, would be more like $2,700 if rates return to a historical average. And yet there are fewer and fewer forecasters and borrowers who expect that to happen. Call it the great capitulation. The surest way to look the fool over the past three years has been to predict interest rates were about to rise. (Guilty here.) All the while the Bank of Canada’s benchmark interest rate has remained pinned at one per cent, and during the worst of the financial crisis was just 0.25 per cent. Over the last decade the rate has spent much of the time at or below the two per cent mark.

We’re pretty much at the point now where it’s just accepted interest rates will stay low. And not just for the next year or two. Bill Gross, the bond king who manages the world’s largest fixed-income fund at PIMCO, and who famously, and wrongly, bet big in 2011 that U.S. interest rates were set to rise, now believes we’re in a semi-permanent era of low rates. “The U.S. (and global economy) may have to get used to financially repressive–and therefore low policy rates–for decades to come,” he wrote in a recent newsletter. Officials in Canada have certainly gone to great lengths to convince Canadians low interest rates will be here for at least two more years and pose little danger. Stephen Poloz, the governor of the Bank of Canada, regularly dismisses concerns the policy is inflating bubbles.

For now Canada’s towering household debt load has the appearance of being manageable, a point at which the banking and real estate industries hammer away. The household debt-service ratio, the share of income that goes to debt payments, is just 7.17 per cent, about its lowest level ever. But that’s only because of low rates. In 1990 the ratio was 11.5 per cent, at a time when total household debt was $360 billion. Since then debt levels have soared 370 per cent to $1.7 trillion. At the same time interest paid on household debt has gone up just 60 per cent.

But here’s the thing. Central banks have consistently proven themselves incapable of spotting bubbles. It happened in the U.S. It will happen here. And when the consensus among economists, and more importantly, borrowers, is for rates to stay low, it’s a safe bet they’ll be proven wrong. The story of Canada’s love affair with debt has all the makings of a cliffhanger, and those who’ve overextended themselves are standing at the precipice.

Have a comment to share? [email protected]