Canada’s housing market: is it a cooling? Is it a crash?

Here’s a guide to bullish and bearish arguments

Five houses of varying height depicting a graph

Share

Last Friday, rating agency Moody’s announced that almost all of Canada’s biggest banks might be in for a credit downgrade, citing “concerns about high consumer debt levels and elevated housing prices.” It was just the latest warning that, after soaring for 14 years, Canada’s housing market might be finally headed back to Earth.

Now, virtually everyone—from the Bank of Canada and the Finance Department through Canada’s banks to the International Monetary Fund and independent analysts—agrees that housing is losing steam and Canadian wallets are overstretched.

But is Canada’s housing market headed for a gracious landing or a face-forward crash? When it comes to predicting how rough a ride it will be, opinions vary widely.

To help Maclean’s readers make up their minds, we’ve compiled a review of prominent arguments supporting bullish and bearish positions on four key questions about the future of Canada’s real estate and what it all means:

1. Will housing prices cool or collapse?

Here are the latest numbers from the Canadian Real Estate Association and the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation:

- sales of existing homes were down 15 per cent in September 2012 compared to the same month last year. Compared to August, however, they were still up 2.5 per cent.

- during the same period, the seasonally adjusted average price of a Canadian home edged up one per cent compared to year ago levels. Compared to August, home prices were virtually unchanged, dipping 0.2 per cent.

- housing starts fell to a seasonally adjusted annualized rate of 220,215, down slightly from the August figure of 225,328 but still above the 2012 average of 218,400 units.

At least in part, many argue, this slowdown was government-engineered. What we’re seeing is the effect the new rules Ottawa introduced in July, which shortened the maximum length of a government-insured mortgage from 30 to 25 years and capped home equity loans to 80 rather than 85 per cent of the property’s value.

At least in part, many argue, this slowdown was government-engineered. What we’re seeing is the effect the new rules Ottawa introduced in July, which shortened the maximum length of a government-insured mortgage from 30 to 25 years and capped home equity loans to 80 rather than 85 per cent of the property’s value.

And, according to CIBC’s Avery Shenfeld, that was enough encouragement. Discussing the possibility of an interest rate hike—which would make loans more costly and further discourage Canadians from buying homes or borrowing against their own—he writes: “In the face of recent changes in mortgage insurance rules, lofty prices that make taking the plunge a bit less attractive (particularly for speculators), and the end of a catch-up period in which construction has outpaced the trend in household formation, there are good reasons to expect mortgage volumes to settle down in 2013, even without a tightening.”

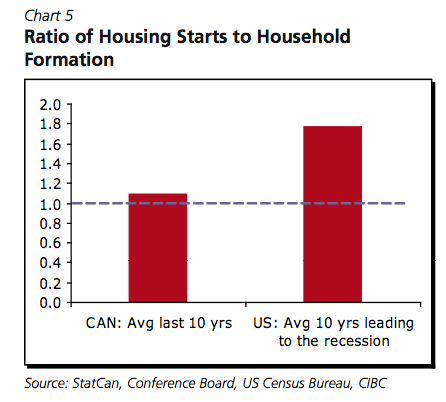

Although, as Shenfeld hinted, Canadians have been building houses faster than they’ve been forming new households, CIBC notes in another report that they’ve done so to a much lesser extent than Americans did in the run-up to the U.S. housing bust. That’s another reason to believe that an “American-style real estate meltdown” is not in cards:

According to economists at TD Bank, home prices are 10 per cent overvalued. If interest rates stay low, TD’s Francis Fong recently wrote in a note to clients, there’s plenty of space for the market to adjust gradually to its “long-term trend levels” in terms of both sales of existing homes and the pace of new construction projects.

Besides, real estate agents’ favourite adage—“location, location, location!—still applies. Not every regional market is headed south. As BMO’s Robert Kavcic noted last month, “Alberta and Saskatchewan posted solid gains, with the latter jumping to the highest level since 1983.” Even Moody’s acknowledges this: “A correction in real estate prices looms as a downside risk for Vancouver and Toronto, but average national home prices are unlikely to decline outright.”

Others aren’t so sure the landing will be all that soft. The 15 per cent drop in resale numbers registered in September, analyst Ben Rabidoux pointed out, was the market’s weakest September performance since 2001.

Others aren’t so sure the landing will be all that soft. The 15 per cent drop in resale numbers registered in September, analyst Ben Rabidoux pointed out, was the market’s weakest September performance since 2001.

Sales of existing home are falling sharply, and prices will soon follow. That construction of new homes is still robust is bad news, as it means the market is creating excess supply that will only further depress home values.

Capital Economics predicts home prices could drop as much as 25 per cent. The dive will leave Canadian consumers hurting and could wipe out as many as 115,000 construction jobs, the firm predicts.

Another telling estimate foreshadowing a sharp correction is the Economist’s price-to-rent ratio, which calculates that Canadian homes are overvalued by as much as 76 per cent.

2. Will Canadians start defaulting on their mortgages like Americans did?

According to the latest estimate by Statistics Canada, which just revised its methodology for calculating the ratio of debt to disposable income to adjust to standards set by the IMF and the UN, Canadians are even deeper in the red than previously thought, owing $1.63 in debt for ever dollar they make.

The BOC called household debt “the biggest domestic risk” to the economy and recently suggested the state of Canadian families’ balance sheets will play a role in its interest-rate setting decisions.

—

Canadian households got the message about debt, and have already started reining in the borrowing. As of March of this year, household credit was growing at the slowest pace since 2002.

Canadian households got the message about debt, and have already started reining in the borrowing. As of March of this year, household credit was growing at the slowest pace since 2002.

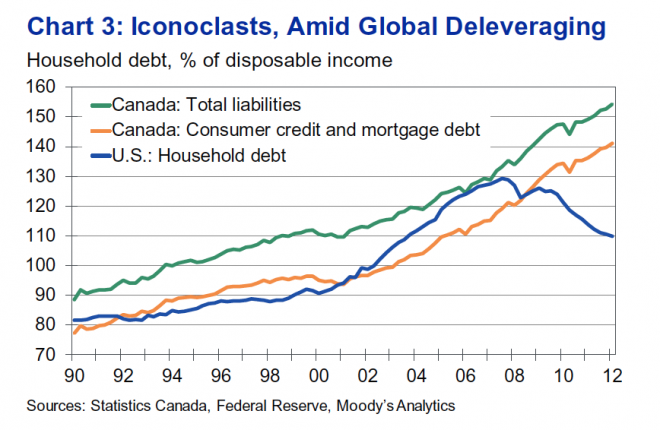

And CIBC’s Benjamin Tal notes that the debt-to-income ratio in Canada has been rising much more slowly than it did in the U.S. prior to the crisis.

Besides, when it comes to mortgage debt, a larger share of Canadians own their homes outright than Americans did at the onset of the U.S. housing crisis: 39 per cent vs. less than 32 per cent south of the border as of 2007.

Finally, according to Moody’s:

Home equity loans and second mortgages have complicated the U.S. foreclosure crisis immensely because of the conflicting incentives of first and second lien mortgage holders. Second liens have limited the ability of some borrowers to refinance their mortgages to take advantage of record low rates. Loan servicers have also run into barriers when trying to modify first mortgages, as the co-operation of second lien holders is needed to preserve the legal rights of the first mortgage-holder during a loan modification. Even if the Canadian housing market should falter and foreclosures should rise, the limited volume of second mortgages among Canadian homeowners suggests that the legal and procedural issues that have plagued the U.S. market would be largely avoided. This would mitigate the spillover effects brought on by the U.S. housing bust. A Canadian housing crisis would likely be shorter and shallower than the U.S. experience.

Canadians are now more indebted than Americans were pre-crisis:

Canadians are now more indebted than Americans were pre-crisis:

Though proportionally fewer Canadians are carrying a mortgage, according to the BOC, the most vulnerable borrowers, those who are channeling 40 per cent or more of their income toward interest charges, are carrying a disproportionate share of debt. While these borrowers amount to just over six per cent of Canadian households, they account for over 11 per cent of household debt.

And Canadians look more vulnerable than Americans in one important respect. While a standard mortgage term south of the border is 30 years, in Canada it is typically five years, meaning that homeowners here are much more exposed to the risk of rising interest rates.

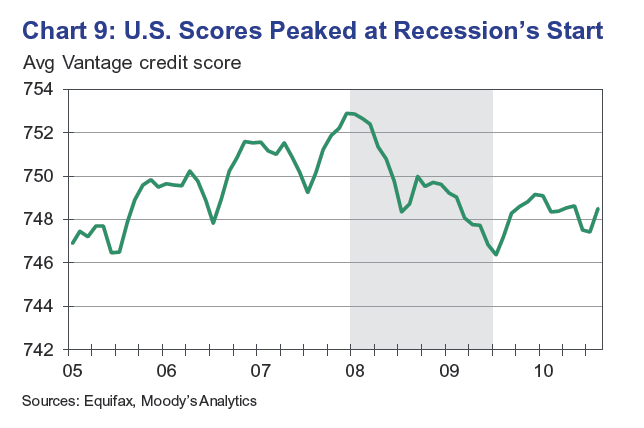

Finally, Moody’s notes that, although Canadians’ credit ratings look good for now, so did Americans’ before the onset of the crisis:

“Rapidly expanded lending,” writes the agency, “can lead to low delinquency rates in the short run, as new loans contribute to outstanding balances while contributing little in the way of new delinquencies for the first few months or quarters after origination. A relatively stable and expanding economy can also mask underlying deterioration in credit quality, as even distressed borrowers have greater flexibility in paying back their loans.”

3. Are the banks safe?

BOC Governor Mark Carney called household debt the greatest domestic danger to Canada’s financial institutions. A three per centage point rise in the unemployment rate, the Bank reckons, would double the rate of mortgage arrears.

Canadian regulators have also becoming concerned with loosening standards among Canadian lenders. Subprime-like mortgages, typically offered to the self-employment and recent immigrants, have become “an emerging risk” to the banking system, according to the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions.

—

According to the BOC, before the financial crisis, “In the United States, the subprime market had grown to account for about 14 per cent of outstanding mortgages … compared with about 3 per cent in Canada.” Non-prime mortgages in general, which include subprime and other rather lax types of mortgages, accounted for 46 percent of all U.S. subprime mortgages in 2006, according to Credit Suisse. While mortgages that require little income documentation may be on the rise today in Canada, they still account for a very small share of the market—probably under five per cent, CIBC’s Tal told Bloomberg News.

According to the BOC, before the financial crisis, “In the United States, the subprime market had grown to account for about 14 per cent of outstanding mortgages … compared with about 3 per cent in Canada.” Non-prime mortgages in general, which include subprime and other rather lax types of mortgages, accounted for 46 percent of all U.S. subprime mortgages in 2006, according to Credit Suisse. While mortgages that require little income documentation may be on the rise today in Canada, they still account for a very small share of the market—probably under five per cent, CIBC’s Tal told Bloomberg News.

Moreover, Canadian banks are largely sheltered against potential losses from residential mortgages, as 75 per cent of them are insured by either the CMHC or private-sector insurer Genworth. And all federally regulated financial institutions are required to insure residential mortgages with a downpayment of less than 20 per cent of the property’s value.

Also, residential mortgages make up 23 per cent of total bank assets, which is relatively low among developed economies.

No one is predicting that a housing downturn would nearly bring down the financial system as the last one did in the States. But many are warning that Canadian banks may not be as sheltered as one might think.

No one is predicting that a housing downturn would nearly bring down the financial system as the last one did in the States. But many are warning that Canadian banks may not be as sheltered as one might think.

“The over-leveraged household sector and a potential deflation of the housing bubble would continue to pose significant risks to the banking system stability in the near term,” reads a report by Roubini Global Economics, the research firm headed by NYU’s Nouriel Roubini, who rose to fame as “Dr. Doom” for predicting the U.S. housing bust and the worldwide recession that ensued.

Canadian banks, for one, won’t be able to rely heavily on the CMHC to absorb mortgage risk for much longer. The housing agency is approaching its $600 billion federally-imposed liability cap. Finance Minister Jim Flaherty also recently hinted the government might soon privatize it.

In any case, mortgage insurance doesn’t offer 100 per cent protection. “In the event of a significant housing downturn,” continues the RGE report, “banks could still face legal risk should there be claim disputes between banks and mortgage insurers, as had happened in the case of U.S. banks.”

Even if Canadian banks are relatively sheltered in terms of mortgage debt, they could still suffer a major hit if dropping housing prices force Canadians to dramatically rein in borrowing or fall behind on their consumer debt. Rabidoux pointed out that, according to OSFI data, chartered financial institutions in Canada hold proportionally significant more HELOC debt than their U.S. counterparts. Outstanding HELOC debt in Canada is $206 billion, or roughly 12 per cent of GDP. That compares to an estimated $649 billions of equivalent outstanding debt in the U.S. in 2010, according to consumer reporting agency Equifax, or roughly four per cent of U.S. GDP.

4. Could all this trigger a recession?

According to the BOC, the ratio of residential investment to GDP has risen from 4.3 per cent in 2001 to a whopping seven per cent in 2012. If the housing market falters, will the economy at large follow?

—

Despite his moniker, Roubini has been sounding a positive note about Canada’s economy and its sputtering housing market. RGE is still predicting that the real estate downturn will be relatively gentle and the economy will slow, but not shift into the reverse gear. Even in the event of a sharper-than-expected housing bust, the research firm forecasts only a mild recession in 2013, with GDP contracting by a modest one per cent.

Despite his moniker, Roubini has been sounding a positive note about Canada’s economy and its sputtering housing market. RGE is still predicting that the real estate downturn will be relatively gentle and the economy will slow, but not shift into the reverse gear. Even in the event of a sharper-than-expected housing bust, the research firm forecasts only a mild recession in 2013, with GDP contracting by a modest one per cent.

Sure, a rise in interest rates—which, sooner or later, must go back up—could be just the kind of spark that sets the house on fire. But, as economist Larry MacDonald notes, “interest rates normally trend upward when there is growth in incomes and jobs, factors that add to housing demand and offset the rate rises.”

Housing bubbles gone bust have plunged economies into recession—including right here in Canada, remember?—well before subprime mortgages and complex derivatives came around.

Housing bubbles gone bust have plunged economies into recession—including right here in Canada, remember?—well before subprime mortgages and complex derivatives came around.

According to Capital Economics, there is “a good chance” that the housing market will become “a significant drag on overall GDP growth in both 2013 and 2014.”

Moody’s, for its part, puts the chance of a recession at between 20 and 25 per cent.

UPDATE (Oct. 31, 11 AM): Just-in real GDP numbers for the month of August show a 0.1 per cent contraction in construction activity despite strong housing starts that month. Meanwhile, the output for real estate agents and brokers was down 6.6 per cent, the fourth straight monthly fall. “August’s disappointing GDP numbers underscore our forecast of paltry growth in the third quarter,” IHS Global Insight wrote in a note this morning, noting that “contracting residential construction and declining output from real estate agents and brokers points to a weakening housing market.”