Five depressing charts about the Canadian economy

Not so much better than everyone else, eh?

Kalexanderson/Compfight

Share

Yay, Canada. We survived the global recession and created lots of new jobs. Now for the bad news: Those jobs have mostly been low-paying, temporary ones with few benefits. And we haven’t created enough of those bad jobs to get back to where employment levels were before the financial crisis.

Those are some of the highlights from a new report released this week by the UN’s International Institute for Labour Studies sizing up the state of the global job market.

Among the more depressing findings of the annual “World of Work” study: The world still needs to create another 14 million jobs to get back to where we were in 2007. Add in the nearly 17 million jobs needed for all the young people who will reach working age this year and globally we’re still short nearly 31 million jobs to get back to pre-crisis employment levels.

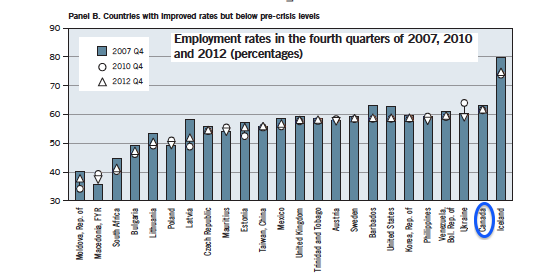

Canada fared better than most when it comes to employment in the years after the 2008 financial crisis. But it’s not exactly a glowing portrait. According to this graph, we made up some ground in employment, but are still below 2007 levels:

Indeed, despite Mark Carney’s assertions in his final speech as Bank of Canada governor last month that Canada now has 480,000 more jobs than before the recession, we’re still behind when it comes to employment.

Indeed, despite Mark Carney’s assertions in his final speech as Bank of Canada governor last month that Canada now has 480,000 more jobs than before the recession, we’re still behind when it comes to employment.

We’ve added roughly 980,000 people to our labour force since 2007 according to Statistics Canada data. Our employment rate has actually fallen from 63.5 per cent in the last quarter of 2007 to 62 per cent at the end of last year. (It was actually lower in April, at 61.8 per cent).

The unemployment rate was six per cent at the end of 2007. It’s 7.2 per cent today. It has come down from its highs above eight per cent in 2009, but it has never recovered to pre-recession levels.

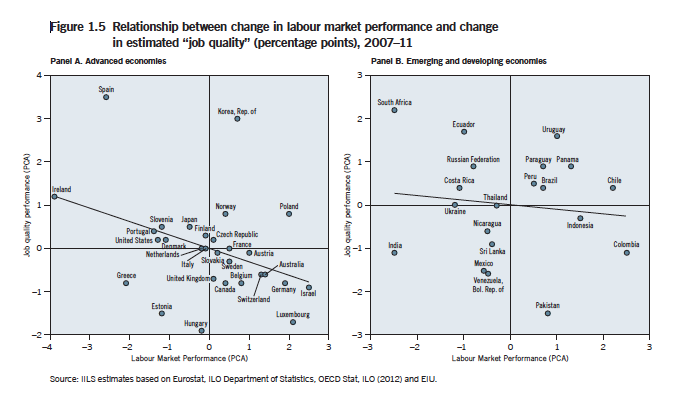

The study also ranks countries on “job quality” — whether the jobs created were well-paying, full-time jobs with benefits or part-time and contract work with little job security.

Here’s the overall picture: The best advanced economies are in the top left – Korea, Norway and Poland. They boosted employment, with most of it coming from good jobs. On the other hand, both employment and job quality declined in Greece, Estonia and Hungary:

Here’s a closer look at Canada, where employment went up, but job quality went down. By contrast, the U.S. has created fewer new jobs overall, but those jobs have tended to be better ones:

Here’s a closer look at Canada, where employment went up, but job quality went down. By contrast, the U.S. has created fewer new jobs overall, but those jobs have tended to be better ones:

This graph also doesn’t square with the familiar narrative that many of the post-recession employment gains in Canada have been full-time jobs in the private sector. The bulk of those jobs, it seems, have been temporary contracts, not permanent positions that come with some measure of job security and benefits. Temporary jobs have grown 15 per cent between 2009 and 2012, compared to job growth of less than four per cent among permanent positions.

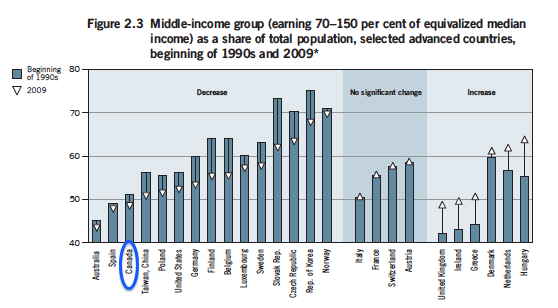

Also, the middle class is shrinking and income inequality is higher than it was in the past in Canada. But we’re better off than some. (One caveat is that the Canadian data only goes up to 2005):

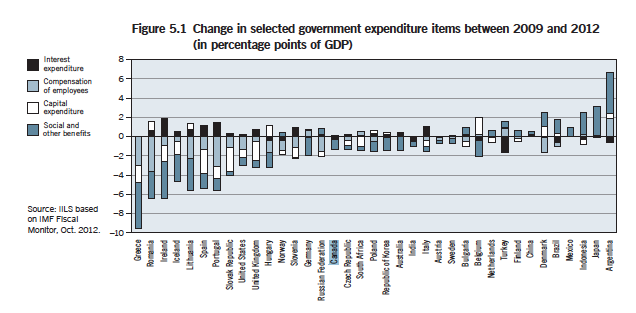

The last graph may be the most surprising. Overall government spending—including provincial budgets—as a share of the total economy has gone down since 2007, with most of the cuts coming from spending on social services and interest payments on the public debt.

The last graph may be the most surprising. Overall government spending—including provincial budgets—as a share of the total economy has gone down since 2007, with most of the cuts coming from spending on social services and interest payments on the public debt.