How a real estate developer’s efforts to silence a critic failed

Fortress’s defamation suit against an independent analyst over his tweets tested a new Ontario law protecting free expression in the public interest

Rathore at the groundbreaking ceremony for a hotel and condo project in Regina.

Share

Last week an Ontario judge tossed out a defamation lawsuit filed by a Goliath of the syndicated mortgage industry against a veritable David of real estate analysts. The ruling didn’t attract much attention, though. Which is unfortunate, because the saga between Fortress Real Developments and independent analyst Ben Rabidoux offers a modern parable for Canada’s overheated housing market. And the case is a crucial early test of a new law in Ontario aimed at deterring so-called SLAPP lawsuits (strategic lawsuit against public participation) that try to shut down free expression that serves the public interest.

For most people, Fortress isn’t a household name, but in the complex world of syndicated mortgage investments, the company is a giant, having deployed $750 million raised from investors in recent years and been involved with more than 70 condo and townhouse projects across the country. The Toronto-based firm has steadily worked to boost its profile. Fortress’s two most senior executives, Vince Petrozza and Jawad Rathore, stood at centre court during a Toronto Raptors game a few years ago to present an $80,000 cheque to the team’s charitable arm, they’re major backers of Raptors’ president Masai Ujiri’s Giants of Africa charity, and they once rang the opening bell at the Toronto Stock Exchange. The company regularly hosts events drawing hundreds of investors and brokers; at a recent conference, Marcus Stroman of the Toronto Blue Jays was a featured speaker. And Fortress’s in-house researcher, Ben Myers, is a regular media commentator, reliably assuring real estate investors and homeowners that any talk of housing bubbles and a household debt crisis in Canada is overblown.

Fortress bills itself as a real estate developer, but in most cases it’s more of a consultant to other developers who carry out the actual construction, providing services like retaining architects, obtaining zoning approvals, marketing projects and “other strategic advice.” The projects Fortress works on are financed, in part, by money raised through syndicated mortgages. As the name suggests, syndicated mortgages take money from hundreds of investors, and use the funds to finance specific projects. The company insists that it doesn’t bring in the money itself, but instead works closely with a group of affiliated mortgage brokers who do. Sometimes, however, it is hard to tell exactly where Fortress ends, and the mortgage brokerages begin—they share nearly identical website designs and, in some cases, employees. As for the pitch to investors, it is undeniably enticing, with the promise of low risks and high returns of eight per cent or more annually. Oh, and it’s all RRSP, TSFA and RESP eligible, too.

What’s not to love?

Plenty. The investments are not nearly as safe nor sound as the slick marketing materials make them out to be. If things go wrong with a project, syndicated mortgage investors have to get in line behind banks and other primary lenders. Syndicated mortgages also exist in a regulatory grey zone. Despite being pitched to investors as a rival to stocks, bonds and mutual funds, they are not governed by the same rules as traditional securities, allowing salespeople to make claims about their performance that stock brokers would never legally get away with. These points have all been made before by the company’s critics, among them Rabidoux, the president of North Cove Advisors, a small research firm that provides analysis on the Canadian economy and the housing market.

Rabidoux’s first run-in with Fortress’s legal department came in early 2015, after he posted a series of tweets about sanctions imposed on Petrozza and Rathore by securities regulators several years earlier. In 2011 the Ontario Securities Commission accused the pair, along with a third man, of engaging “in conduct contrary to the public interest” by selling clients of their debt-management business shares of companies caught up in a B.C. stock scam. Petrozza and Rathore agreed to pay close to $3 million and were slapped with a 15-year ban on trading securities. (The bulk of Rabidoux’s tweets were excerpts taken from a Globe and Mail story—one being a direct quote from the executive director of the B.C. Securities Commission.)

Fortress filed a libel notice against Rabidoux, citing the tweets. In a settlement to that suit, Rabidoux deleted them, apologized, and “completely and without reservation” retracted his comments. He also promised not to make any “comments, suggestions, opinions or statements of any kind whatsoever” about the executives or their company. If Rabidoux broke that promise, he would have to cough up $10,000 or face another lawsuit.

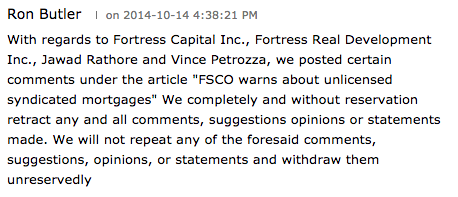

If it seems strange that a company as large as Fortress would be so vociferous in its pursuit of someone’s tweets—Rabidoux’s Twitter account has just 3,800 followers—it helps to understand that the company has earned a reputation for regularly threatening to sue those who comment about it unfavourably on social media and in online forums. Here’s an example:

Rabidoux remained active on Twitter, and though he never mentioned Fortress, Petrozza or Rathore by name, the company’s lawyers contacted him again in December 2015 and demanded he pay $10,000 for a second series of “defamatory” tweets.

It’s worth pausing for a moment to consider the tweets Fortress found so offensive this time. In one, on Dec. 7, 2015, Rabidoux wrote, to no one in particular, “How’s that syndicated mortgage investment on Calgary preconstruction condo development going for you? Asking for a friend?” In another missive, Rabidoux thanked a Twitter user who called him “our nation’s Michael Burry”—a reference to the U.S. short seller who became a star character in author Michael Lewis’s The Big Short (and in the eponymous 2016 movie) for spotting rampant fraud in America’s housing market before others did. Fortress also cited a follow-up tweet from a prominent U.S. short seller and frequent critic of Fortress, Marc Cohodes, who told Rabidoux: “You’re a man amongst boys and those clowns at Fortress couldn’t carry your jock strap.” (Cohodes is one of several U.S. investors betting against Canada’s housing market.)

However another pair of tweets touched on a topic that had upset Petrozza and Rathore before: references to their run-in with the OSC. Under Canada’s regulatory mishmash, the ban imposed by the OSC didn’t extend to the pair’s other business venture, Fortress, since syndicated mortgages are overseen by another regulator, the Financial Services Commission of Ontario (FSCO). In the tweets, Rabidoux predicted the OSC would soon assume responsibility for regulating the industry, and “slam the door on shadier operators… some operators will immediately be in trouble if syndicated mortgages [are] deemed securities since some are already sanctioned by the OSC.”

After receiving the letter from Fortress, Rabidoux deleted the tweets again, but didn’t pay the $10,000 Fortress demanded. Last February the company filed a defamation suit demanding $150,000 in damages.

But in the wake of Fortress filing its claim, a lot has changed in the world of syndicated mortgages, and those changes have buffeted Fortress and other companies in the sector.

For one thing, a panel set up by the Ontario government to review the mandate of three provincial financial watchdogs, including FSCO, recommended that the “regulatory gap” in which syndicated mortgage companies operate should be closed. The products, the panel wrote, should be subject to the same rules and regulations that govern stock market investments. (Since then the Ontario government has adopted the panel’s recommendation to create a new Financial Services Regulatory Authority; the government hasn’t yet said how syndicated mortgages will be treated.)

The panel also said it was “seriously concerned” by cases of individuals being disciplined by one regulator, only to operate in other parts of the financial market under different regulators. When a securities salesperson is barred, the panel urged, a regulator “should have a duty to consider whether that person should be permitted to continue selling segregated funds or syndicated mortgages.”

Some Fortress projects have also run into trouble, and investors have filed several proposed class-action lawsuits against the company. With regard to one struggling project in Barrie, Ont., plaintiffs allege Fortress misrepresented the risks of the project, how the investment funds would be used, and how much of investors’ money would go directly to Fortress’s bottom line. As of December, claims against Fortress added up to $100 million, a lawyer involved with some of the lawsuits told Mortgage Broker News recently.

In a statement, Fortress spokesperson Natasha Alibhai said “the allegations made in those proposed class actions about the defendants and the syndicate mortgage loans are untrue, highly misleading and are clearly aimed at damaging the reputation of Fortress and Fortress projects in an attempt to benefit Fortress’s competitors.” She said the defendants are challenging the class action proposal with a hearing set for May 2017. “Fortress is confident that these proposed class actions will be shown to be entirely without merit,” she wrote.

And yet troubles persist. Investors in one Calgary condo project being developed by Fortress and self-anointed “condo king” Brad Lamb received a letter in September informing them that payments to investors were being delayed as a result of a “lack of funds closing into the project’s interest reserve.” The letter assured investors that mortgage brokers were “actively raising money for the project” from new investors to “bring the development budget up to date, and top up the [interest reserve] for current and future payments.” Meanwhile, another project to build Winnipeg’s tallest tower appears stalled because the city has refused to provide a $6.5-million grant to Fortress, without which the company has said the project isn’t feasible.

But something else changed last year, wholly unrelated to real estate, that fundamentally helped Rabidoux in his legal fight against the company. In late 2015, as Fortress was scouring Rabidoux’s Twitter feed for slights, the Ontario government introduced a law, the Protection of Public Participation Act, that created a new way for defendants to fight defamation suits. Ontario’s so-called anti-SLAPP law doesn’t alter existing defamation laws, but if a defendant introduces it as a motion, the plaintiff has to prove several things, the most important being: was the defamation so damaging to its reputation that it outweighs the potential harm to the public interest in letting the suit proceed?

Rabidoux argued his tweets were in the public interest and that Fortress’s lawsuit was an effort to “gag” him. In her ruling, issued on Jan. 11, Justice Andra Pollak agreed with Rabidoux that his comments about the OSC, his criticism of syndicated mortgages and condo developments were all “matters of a ‘public interest.” Justice Pollak didn’t buy Fortress’s argument that dealing with Rabidoux’s tweets had cost it time and money. “There is no evidence of any specific damages suffered by the plaintiffs as a result of Mr. Rabidoux’s tweets,” she wrote. As such, she dismissed the case.

In a statement, Rabidoux’s lawyer, Gil Zvulony, said his client is happy to have the case behind him. “Being sued can be very distressing,” he wrote. “Mr. Rabidoux was sued by four deep-pocketed plaintiffs for relatively innocuous and ephemeral tweets.”

As for Fortress, its spokesperson Alibhai said in a statement that the judge did not reject Fortress’s allegation that Rabidoux’s comments were defamatory. The statement also said that the company doesn’t agree with the judge’s decision with regards to the anti-SLAPP motion, and that it plans to appeal. “Fortress welcomes open public commentary on its projects,” the statement read, “but believes that people should not be permitted to make untrue and defamatory comments about Fortress that are damaging to Fortress and the stakeholders in Fortress projects.”

This wasn’t the first case to test Ontario’s anti-SLAPP legislation but it is among the earliest, and could prove important as other analysts, journalists and commentators dig into the activities of companies operating in Canada’s frothy real estate sector. After all, with so many fortunes tied up in Canada’s housing bubble, this is unlikely to be the last defamation lawsuit filed against those who raise uncomfortable questions about what’s driving the market. “This is not only a victory for Mr. Rabidoux,” his lawyer said, “but a precedent for others who may be faced with similar lawsuits.”