How climate cheaters make the rest of us pay

Volkswagen may have been caught in the most public scandal. But you hardly have to own a VW to be taken for a ride.

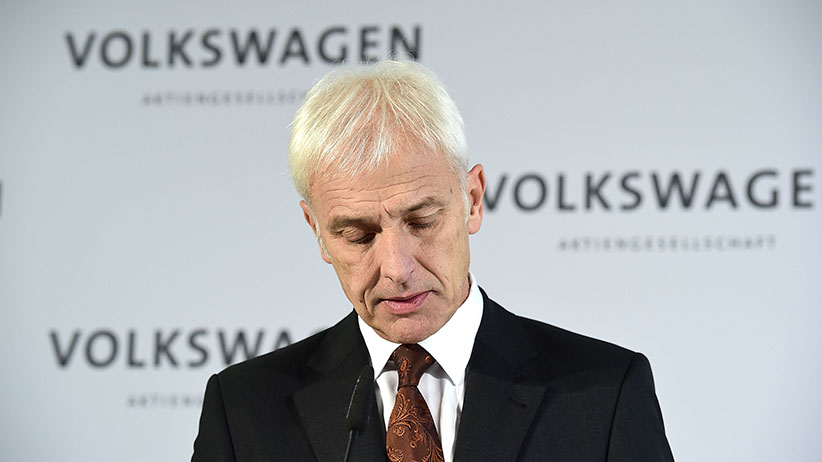

Matthias Mueller, CEO of Volkswagen Group, speaks to the media following a meeting of high-ranking Volkswagen managers on November 20, 2015 in Wolfsburg, Germany. Volkswagen officials are scheduled to meet with officials in the USA to present details on how the company will fix 482,000 Volkswagen vehicles sold in the U.S. affected by the emissions cheating software to comply with U.S. emissions standards. (Alexander Koerner/Getty Images)

Share

The Volkswagen emissions scandal has been a gut-churning ride for VW owners and shareholders—to say nothing of the automaker’s top executives. To watch from the sidelines is to feel the guilty relief of a driver who has narrowly avoided a freeway pile-up.

Over the last week, the crisis deepened, as the company acknowledged that 2016 models—including some gasoline-powered cars—are showing emissions anomalies similar to those in 11 million diesel-powered cars that were rigged with software to cheat emissions tests.

But the impact of this fiasco affects all of us, raising issues that will surely fuel debate when the Paris climate change summit opens on November 30.

How can we measure our progress in the war against climate change when major companies—and even governments—misstate their impacts on the atmosphere? How can we put a price on carbon if some emitters’ numbers are fanciful? How can we fairly tax it? Doesn’t wide-scale misreporting cast any such model into doubt?

The scale of misstatement is not known, of course, but that’s precisely the problem. No one outside the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency seems to monitor compliance with any rigour.

What we do know is that Volkswagen isn’t the only carbon dissembler. A year ago, the Hyundai Motor Group and its corporate cousin, Kia Motors, shelled out $100 million in a settlement with the E.P.A. and took a $200-million hit in greenhouse gas credits for misstating the emissions of 1.2 million cars and trucks. Emissions trading schemes like the one in Europe, meanwhile, have been rocked in recent years by scandals in which credits were traded repeatedly to facilitate tax fraud rather than for their stated purpose—to use market forces to reduce greenhouse gases.

Even Tesla, that darling of the environmental movement, has come under scrutiny by critics who say its electric cars leave a bigger carbon footprint than widely thought.

That’s just the corporate world. Of greater concern still is vital data provided by countries like China, which recently “revised” reports to show that it’s been burning 17 per cent more coal annually than originally acknowledged. The change—done without announcement or fanfare—suggests the country spewed nearly a billion tonnes more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere between 2011 and 2013 than previously thought.

That’s about 38 per cent more than Canada’s entire annual output of greenhouse gases.

Ross McKitrick, a University of Guelph economist who studies sustainable commerce, says these cases reinforce existing doubts about our ability to set fair emissions targets, country by country, and to measure progress.

“Generally, if we can track the consumption of fossil fuels we can estimate CO2 pretty accurately,” he says. “The problem is that countries like China that mine their own coal have under-reported their consumption.” Moreover, says McKitrick, if countries claim to have made cuts they didn’t, that raises pressure unfairly on the rest of the world to do their part to lower global output: “The honest countries incur costs that others do not.”

Misdirection efforts by the likes of VW, meanwhile, can undermine the system at the regional level, because cap-and-trade systems rely on accurate data for authorities to set emissions allowances by industry or company. Take the example of a European car rental company with a large fleet of VWs: it has now contributed far more to overall emissions in the past few years than it knew; in the meantime, government authorities might have set allowances for other emitters unfairly low in their effort to hit national emissions targets, forcing those enterprises to buy carbon credits or make costly upgrades to reduce their footprints. Again, the honest must pay.

It certainly makes efforts to punish carbon cheaters seem inadequate. Last Thursday, the European Commission extended a 10-day deadline it gave Volkswagen to provide full information on its cars’ emissions under EU environmental rules. But if it weren’t for testing of the cars by the E.P.A., the commission wouldn’t have known anything was amiss to start with. VW now has until the end of the year to file its report, and even then authorities may not have legal grounds to prosecute the company.

That’s not to say carbon pricing schemes can’t work. McKitrick thinks they’re feasible within the borders of countries like Canada, where, at least theoretically, emissions claims can be checked. And some advocates have rushed to the defence of China, noting its revisions came about due to improvements in its pollution monitoring that for the first time picked up coal usage by smaller steel and cement companies.

“The good news is that China’s not hiding from this,” Barbara Finamore, an attorney with the U.S. Natural Resources Defense Council told Huffington Post. “They’re working hard to improve the ability to monitor coal use and carbon pollution, so that’s where these figures are coming from.”

Maybe so. But it does make you wonder what else lies out there require revision—or in VW’s case, aggressive investigation—and who is going to pay for it. If curbing climate change requires an emissions cop on every corner, it could be a lot more expensive than anyone anticipated.