Is there an auto bubble on the horizon?

Strong auto sales are dangerously dependent on cheap debt. Are auto loans the next ‘Big Short’?

New Ford vehicles are seen at a parking lot of the Ford factory in Sao Bernardo do Campo February 12, 2015. Automobile sales in Brazil this year are expected to post their biggest drop in 16 years, underscoring the depths of an industry crisis that has triggered layoffs and trade tensions, national dealership association Fenabrave said on March 3, 2015. New registrations are expected to fall 10 percent from a year earlier and could reach their lowest level since 2009, following steep drops in January and February.Sales of cars, trucks and buses tumbled 28 percent in February from January, Fenabrave reported on Tuesday. January sales had plunged 31 percent from December. Brazilian consumer and business confidence is crumbling as rising interest rates and accelerating inflation squeeze household budgets, choking off one of the few sources of economic growth in recent years. Picture taken February 12, 2015. (Paulo Whitaker/Reuters)

Share

Ford Canada’s latest marketing campaign promises to simplify the stressful task of buying a new car, truck or SUV. No more “starting at”-teases or “bi-weekly” payment options. Instead, consumers will encounter prices that reflect Ford’s most popular trim levels—heated seats, keyless entry, four-wheel drive—and payments that come due “every two weeks.” Says a recent ad: “Ford is adopting a more straightforward approach so you know what you’re getting into.”

But a growing number of critics are worried that a lot of car buyers don’t fully understand what they signed up for when they drive off the dealer’s lot. That’s because more and more Canadians are agreeing to extra-long financing periods, up to eight years, in order to keep monthly payments affordable. While that makes it easier to purchase a brand-new compact SUV with a leather interior and all sorts of electronic doodads, it also piles on thousands more in interest charges—particularly if buyers don’t qualify for the cheapest rates. Worse, many will find themselves underwater on their loans for years, making it difficult to sell their depreciating car or truck if they lose a job and can’t make payments, as was the case for many former oil workers in Alberta when crude prices crashed.

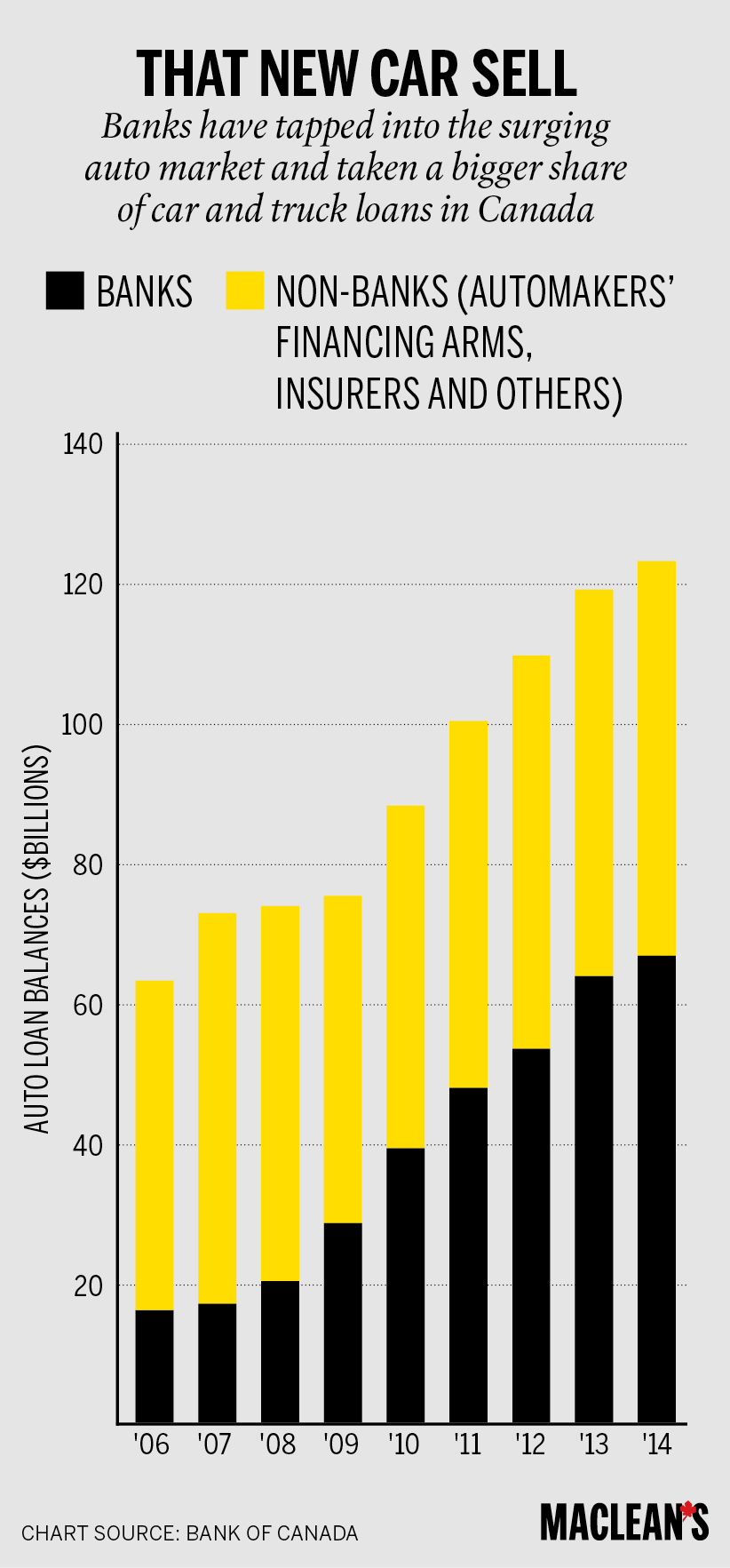

A recent report by the Financial Consumer Agency of Canada, or FCAC, also referred to an “auto-debt treadmill” as some car owners trade in their slightly used vehicles for brand new ones before they’ve built any equity, rolling over the old debts and taking on ever higher interest rates in the process. FCAC warned a future rise in interest rates could “increase the potential for a credit crunch” in the auto finance market by squeezing these already stretched loan-to-value ratios. As for lenders themselves, the Bank of Canada says a doubling in auto loans to $120 billion over the past decade needs to be monitored closely, particularly since roughly one-quarter of those loans went to people with poor credit.

It’s yet more evidence of how years of cheap borrowing—households owe a record $1.65 for every dollar they earned, according to the latest Statistics Canada data—are pushing Canadians ever deeper into debt and making them increasingly vulnerable to a rise in interest rates or a lost job. While banks point out that car loans account for a relatively tiny portion of their portfolios, critics say they’re mostly worried about the broader effects of a car-loan crisis on a weakened Canadian economy. “Just because something’s small doesn’t mean it’s not dangerous,” says Jean-Paul Lam, an associate professor of economics at the University of Waterloo. “The U.S. subprime mortgage market was also very small compared to the overall mortgage market.” And everyone knows how that turned out.

Alongside housing, sales of new vehicles have been one of very few gravity-defying sectors of the Canadian economy in recent years. Even as overall economic growth slowed to a near standstill last year, consumers continued to wander through dealers’ airy showrooms and ink purchase agreements for nearly 1.9 million new cars, trucks, SUVs and crossovers, marking the industry’s third year in a row of record Canadian sales. But while carmakers attribute the impressive performance to pent-up demand held over from the dark days of the Great Recession, it seems obvious that easy access to cheap money, stretched over longer periods, has played an outsized role in keeping their assembly plants humming.

Where once most Canadians financed their car purchases over three to five years, more than half now opt for so-called “extended financing periods” that extend as long as seven or eight years, with the average loan term now clocking in at 74 months, according to FCAC. The problem is simple: most buyers don’t plan to keep their car that long, with FCAC estimating the average auto loan is broken sometime during the fourth year. In the case of a $35,000 SUV financed at four per cent over eight years, FCAC says consumers who try to sell or trade in their vehicles at the four-year mark will still be “underwater” to the tune of $9,000.

Why is this happening? Mostly, it’s a response to the implosion of the vehicle-leasing market during the 2008 financial crisis. With vehicle-leasing companies balking at the risks, the percentage of new vehicles sales done through leases in Canada plummeted below 10 per cent in 2009 from a high of nearly 50 per cent just a few years earlier (vehicle leases have since recovered to about 25 per cent of the market). So banks and other lenders stepped in to fill the void by taking advantage of low interest rates and extended loan periods to mimic typically cheaper monthly lease payments.

Related: Canadians are in a debt trap

The tactic worked—maybe a bit too well. New car sales boomed as buyers fixated on their monthly payments instead of how much their vehicles actually cost, leading to some extraordinarily bad financial decisions. In 2014, CBC made waves when it told the story of a B.C. couple who were effectively paying $44,000 for a Dodge Avenger because of the 25 per cent interest rate their bank charged them on a seven-year, $21,000 loan. “We’ve been robbed,” Enzo Gamarra told the network, whose story prompted other Canadians to come forward with similar tales. In all, it’s estimated about one-quarter of the $120 billion in outstanding auto loans in Canada are what’s known as “near-prime,” meaning they’ve been made to borrowers whose credit histories don’t qualify them for the lowest advertised rates.

Michael Hatch, the chief economist of the Canadian Automobile Dealers Association, says such horror stories aren’t representative. He argues the “vast majority” of car buyers can comfortably finance their loans and do so at rates close to zero per cent. He also takes issue with FCAC’s claim that extended loan periods are out of sync with Canadians’ car-purchase habits, arguing that, thanks to improved vehicle technologies, Canadians are keeping their cars and trucks longer than ever. “A three-year-old car coming off a lease with 50,000 km has as much life left on it as a brand new car would have had 10 or 15 years ago,” says Hatch, who also notes average delinquency rates on Canadian auto loans stand at just 1.3 per cent, though that’s up 10 per cent from a year ago thanks mostly to economically hard-hit Alberta and Saskatchewan. “Nobody in the industry is advocating for 10-year loans, but where we are today is wholly sustainable.”

Others smell blood in the water. They point to the U.S., where auto lending has followed a similar playbook, and several hedge funds are convinced they’ve discovered, in the words of Bloomberg News, “the next Big Short,” a reference to the Oscar-winning film about traders who prophetically bet against the U.S. housing market before Wall Street’s meltdown. That’s because U.S. auto-loan default rates are similarly on the rise and there’s mounting concern about the health of asset-backed securities that—surprise—contain repackaged, subprime car loans. That said, America’s US$1 trillion of outstanding auto loans is but a drop in the oil pan of U.S. bank portfolios, making reckless auto lending an unlikely candidate to take down the U.S. economy in the same way the collapse of subprime mortgages did.

But the same can’t easily be said of Canada. Our housing market never crashed and consumers have never been more indebted, owing roughly $1.9 trillion at last count. Deceptively expensive auto loans made to people who can’t afford them could well prove to be the pothole that sends the whole, creaking jalopy into the ditch. “We know from a lot of studies that people tend to default on mortgages and other types of loans first,” Lam says, referring to the fact even financially distressed families are reluctant to abandon their cars because they need them to travel to job interviews, pick up groceries or take the kids to school. “That’s one of the biggest risks in terms of contagion.”

In such a scenario, it’s not the banks who are at risk, but individual consumers and the broader economy that increasingly depends on their borrowing and spending. Just look at what happened in Alberta, Lam says, pointing to the more than 40,000 oil-related job losses that caused local housing prices to slide, delinquencies on auto loans to spike and briefly pushed the entire country into a recession. “These things can have a big effect.”

Carmakers always promise the freedom of the open road. But Canadians who bought too much, and put down too little, could soon find themselves driving into a dead end.