Manitoba’s choice

Taxing high earners wouldn’t have filled provincial coffers, writes Kevin Milligan

Free Grunge Textures, via Compfight. Licence terms: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

Share

Kevin Milligan is associate professor of economics at the University of British Columbia.

Manitoba stands alone in Canada, and not just for its mosquitos and late springs. It also stands alone in resisting a wave of higher provincial income tax rates on top earners—a wave that’s slowly sweeping Canada from coast to coast. Nova Scotia was first on this trend, creating a new higher tax bracket for those making above $150,000 in 2010. Ontario and Quebec announced similar brackets to take effect in 2013, and B.C. looks set to join the others in 2014.

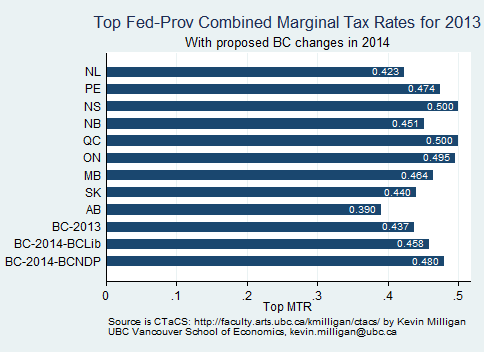

In the chart below, I show the tax rate for high earners across provinces in 2013, along with two potential paths for B.C. in 2014 depending on the results of the upcoming provincial election. The top rates range from 50 per cent in Nova Scotia and Quebec to 39 per cent in Alberta. If the NDP proposal for B.C. is implemented, the top tax rate there will move from 43.7 per cent in 2013 to 48 percent in 2014.

The key question to ask here is, why did all these provincial governments feel the need to add one more tax bracket at the top? They might have done so out of a concern for social justice. Increasing income inequality is real, and some Canadians feel strongly that those at the top who have made out very well over the past couple of decades should make greater tax contributions. However, as Stephen Gordon recently reminded us, if the goal is to raise revenue, we must always be careful about our expectations from higher rates.

Which brings us back to Manitoba.

In the recent provincial budget, the province’s NDP government chose to move the PST up one point, from seven to eight per cent, but left the income tax untouched. Why?

My guess is the Manitoba government actually wanted to raise revenue, rather than just run a tax-the-rich flag up the flagpole. The higher PST in Manitoba will raise about $277 million in 2013-2014. No realistic extra income tax bracket for the rich could hope to come close to that revenue number.

Let’s look at the math. According to public data from the Canada Revenue Agency, there were only 11,450 taxpayers with income over $150,000 in Manitoba in 2009. Their total taxable income above the $150,000 threshold comes down to about $1.25 billion. If you project that income forward to 2013, you can calculate what provincial income tax rate would be needed in a hypothetical $150,000 bracket to generate the same $277 million the higher PST will bring. (Note that I am not accounting for the shrinkage in reported taxable income that would likely result from higher rates as some high-income taxpayers rearrange their finances to minimize the hit.)

My calculations suggest the current top bracket rate of 17.4 per cent in Manitoba would have to approximately double to 36 per cent to equal the PST yield of $277 million. In addition to the 29 per cent federal top rate, this would take the combined Manitoba-federal top income tax rate over 60 per cent. Needless to say, tax rates set that far out of line with other provinces would be dangerous policy for Manitoba. In other words, there just isn’t enough money to be squeezed out of Manitoba’s high earners to significantly raise provincial revenue.

Of course, the Manitoba government had many other budget options. It could have chosen to lower spending by $277 million, to increase income taxes for middle earners by a few points, or to let the deficit come in $277 million higher. But if the choice was between a higher PST and a high income tax bracket, the PST was the only realistic short-run option. (In the long-run, a move to join the HST system would be far more beneficial, but that is a debate for another day.)

The lesson from this Manitoba exercise for all Canadians is clear: provinces might wish to push up tax rates on high earners in pursuit of fairness, but turning up the heat on the rich isn’t going to generate the kind of revenue that can feed the continuing growth in provincial government spending.