Mexico’s president is a champion of the wrong people

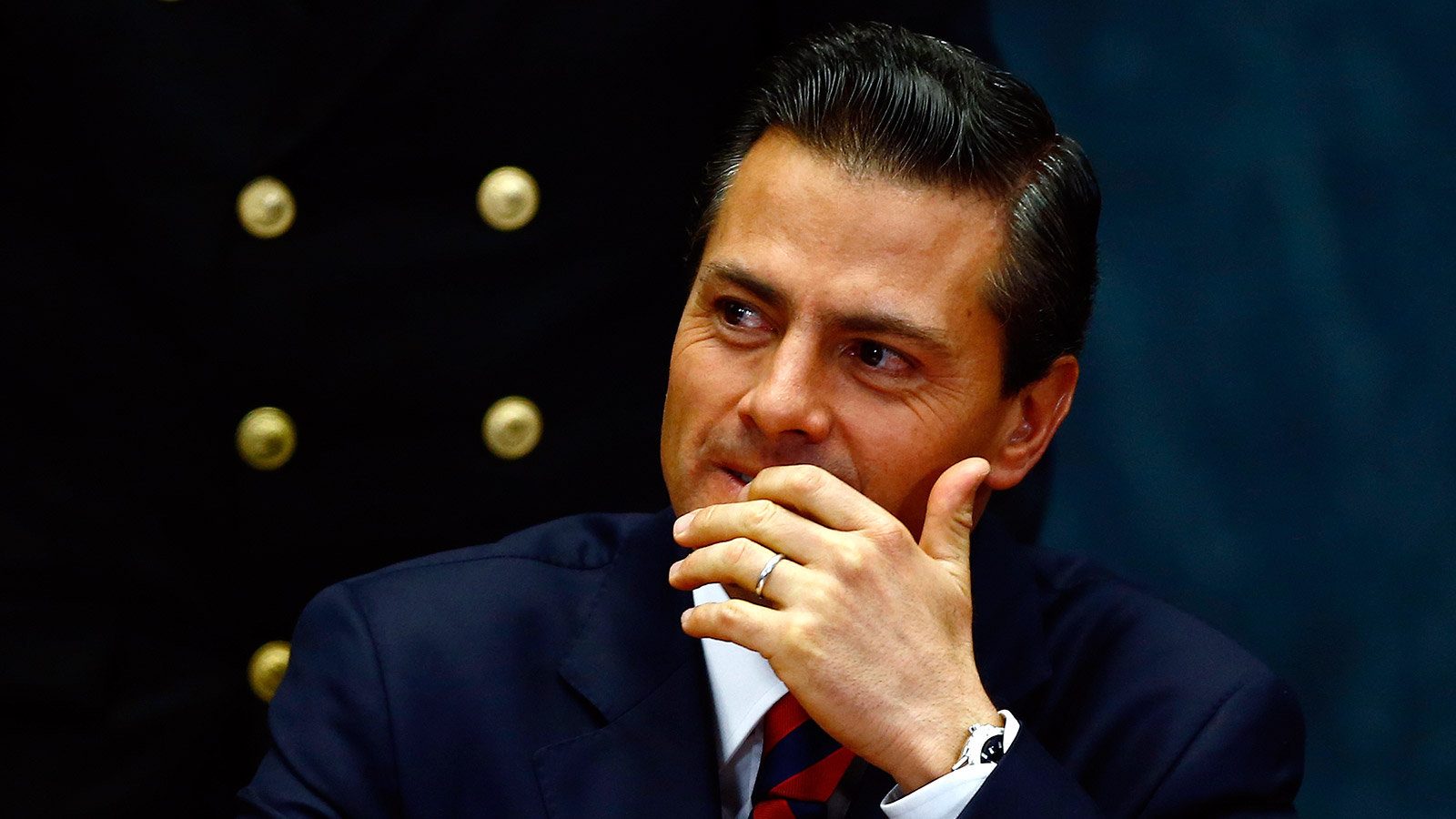

To foreign investors, Enrique Peña Nieto is a dashing reformer. At home, his message of change is flopping.

Tomas Bravo/Reuters

Share

Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto brought plenty to boast about to his state-of-the-nation address last month—an event often more an exercise in exaggeration than informing the public. He boasted of achieving legislative approval for 11 structural reforms, including overhauls in education, energy, taxes and telecommunications. He announced plans for a new Mexico City airport, which would be the biggest in the world. The president also spoke of less crime being committed. Mexico, he said, “Dared to change, and has its sights set on the future.”

Few presidents or politicians can present themselves as agents of change quite like Peña Nieto. He has impressed foreign investors and analysts who have been especially won over by his willingness to open the state-run oil industry to private players. It was an act previously thought impossible: Many Mexicans consider the 1938 expropriation of the petroleum sector and the expelling of foreign oil companies as an important act of sovereignty. Even billionaire investor Larry Fink, CEO of the behemoth BlackRock money management firm, opined that, if he were a Millennial, “I’d try my luck in Mexico.”

But what creates confidence abroad is driving disquiet in Mexico, where a weary populace wonders if it’s witnessing change or watching a re-run of the early 1990s, when a wave of reforms, privatizations and the approval of NAFTA promised to make Mexico “First World.” Mexico curbed inflation and found economic stability after those reforms. And NAFTA has opened an economy once so closed that candy bars were sold as contraband. But what Mexicans mostly remember of that era is the sluggish economic growth, abusive monopolies and the formation of fabulous fortunes—none bigger than that of Carlos Slim, who became the world’s wealthiest man within two decades of buying Teléfonos de México with a clause keeping out competition for six years.

“I am extremely satisfied with the way things have worked in Congress, but I’m very skeptical that [reforms] will be applied the way they should be,” says Eduardo García, publisher of the online business publication Sentido Común, adding that he worries the biggest benefits will go to a small number of people.

Polls show growing pessimism. Peña Nieto’s approval rating is running under 50 per cent (historically low, by Mexican standards) while 60 per cent express dissatisfaction with his handling of the economy (which grew 1.1 per cent in 2013), according to a Pew Research Center survey. The pessimism, says independent economist Jonathan Heath, is rooted in an unhappy history of false starts and peso crises. Heath recalls many Mexicans sensing that something was amiss in 1994 and buying U.S. dollars to protect their assets, even as foreigners invested more. The peso subsequently crashed. ‘We know that governments have promised, but never delivered, so we’re just used to it,” he says.

Foreigners are once again showing optimism for Mexico as the emerging market of the moment. The Financial Times called Mexico an Aztec tiger. Time magazine put Peña Nieto on its cover with the headline, “Saving Mexico”—provoking indignation and prompting El Deforma, Mexico’s version of The

Onion, to state it had nothing to do with the story.

Peña Nieto, who has been in office for a year and a half, seems unfazed by the poor polls and speaks of the reforms needing time to produce results. He portrays himself as a man of the people, posing for selfies at presidential events, and as a man of action. To win his reforms, he brokered a broad deal with badly divided opposition parties known as the “Pact for Mexico.”

Yet, despite the co-operation in Congress, Mexicans express an alarming disenchantment with democracy and a suspicion with political deals. Just 37 per cent said democracy was preferable to other forms of government, the lowest level in the Americas, according to Latinobarómetro. Many observers speak well of the pact, but say the sight of the opposition siding with a president elected with 38 per cent of the vote brings back bad memories of one-party rule under Peña Nieto’s Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI.) “We’ve gone a step back in democracy . . . to the days of either you were inside the PRI or you didn’t have any political power,” says Manuel Molano, adjunct director of the Mexican Institute for Competitiveness think tank.

The president’s narrative of change also seemed at odds with his state-of-the-nation address, which saw the invited politicians and business elite parking their SUVs (and body guards) in the Zócalo—a massive square dating to Aztec times in central Mexico City, where social movements often organize marches. “The message was terrible,” says Guadalupe Loaeza, an author and social critic. “They put their cars there, and felt like they had the liberty and impunity to do so.” Peña Nieto says his reforms will remedy that kind of inequality. He still has his work cut out for him.