The battle for the middle class

As politicians target their votes, economists debate their incomes, writes John Geddes

Chrystia Freeland, with Liberal leader Justin Trudeau

Share

In this week’s issue of Maclean’s, on newsstands today, I report on the political debate over the state of Canada’s “middle class,” which took on new urgency this month with Liberal Leader Justin Trudeau’s appointment of former journalist Chrystia Freeland, his party’s candidate for the upcoming Toronto Centre by-election, as a key economic advisor.

Not only is Freeland a noted author on the subject of income inequality, on the strength of her 2012 book Plutocrats: The Rise of the New Global Super-Rich and the Fall of Everyone Else, she’s up against an NDP nominee, Linda McQuaig, who has taken her own hard-hitting, left-wing position on the issue in books like 2011’s The Trouble With Billionaires: How the Super-Rich Hijacked the World and How We Can Take It Back.

Trudeau had already made championing the ostensibly hard-pressed middle class his big theme. And, of course, that amounts to a direct challenge to Prime Minister Stephen Harper, whose hold on power depends on his continued lead among suburban, middle-class voters. This is nothing new—both the late Jack Layton and the vanquished Michael Ignatieff tried to style themselves as champions of the middle class in the 2011 election.

But the real state of the middle class in Canada remains a matter of contention among economists. In my story, I frame that debate. Here are edited interviews with two leading economists, with conflicting opinions, who feature in the story.

Miles Corak is a professor at University of Ottawa and an internationally respected expert on income inequality. Stephen Gordon is an professor a Laval University, best known to Macleans.ca readers for his contributions to our Econowatch blog, where the state of the middle class has already been the subject of lively debate.

Miles Corak: “Families work harder, work longer.”

Maclean’s: What’s your perspective on the prosperity of Canada’s middle class? Are their incomes stagnating, as we so often hear?

Corak: In part it depends upon the timeframe we adopt in looking at this. This is going to lead us to particular causes. Some people look from the mid-90s. That’s a low point in the data, in part because of the long and severe recession we’d had. Since then there has been a recovery in median incomes, a natural recovery due to coming out of a recession, but also because our economy, particularly the Ontario economy, was hooked into a booming American economy, party substantive, partly the dot-com boom. Another reason, particularly after about 2000, had to do with commodity prices.

Q. What’s wrong with growth based on those sorts of factors?

A. This commodity price boom might go on forever, but I doubt it. And, in spite of these very strong booms, the level of median incomes hasn’t returned to what it was in the late-1970s.

Q. So if we need to see beneath cycles of boom and bust, what underlies it all?

A. It’s important to go to the very root of this—wage rates. You can see families, particularly in the lower half of the income distribution, responding to polarization in wage rates. To maintain their standard of living, families work harder, work longer. Both spouses are working. They get more education. They have fewer kids and they marry later. There are all these adjustments that respond to the deep structures—technological change and globalization—that determine wage rates.

Q. If the pressure is mostly on the lower income earners, why all the attention to those in the middle?

A. At the lower end, you’ve got a very significant fall in wages. But it doesn’t mean you shouldn’t be concerned about the middle. Yeah, they’re holding their own. It doesn’t mean families aren’t more stressed; it doesn’t mean they haven’t adjusted in other ways. They’ve got to run harder to stand still. And I suspect, I don’t know, but I suspect for reasons of giving an agenda a larger voice it’s important to speak for the broad groups, not just to focus on the lower end.

Q. You’ve written, on a closely related issue, social mobility in Canada is quite a lot better than in the U.S. Isn’t that cause for some pride in the Canadian system, and optimism about the kids of those whose incomes are at the median or below?

A. This is the importance of a long-term perspective. [My research] looks at a group of people born in the early- to mid-1960s, who went to primary and secondary schools of the ‘60s and ‘70s, the universities of the ‘80s, and hit the labour market of the ‘90s. These kids came of age in a period of much more equality. The dual-earner family was not as prevalent as it is now, so they came on average from a much more nurturing family background, they went to schools that were relatively more homogenous, and they had their university education significantly subsidized when tuition fees were much lower, and they hit a booming labour market. Now, compare that to someone who was born ten years ago.

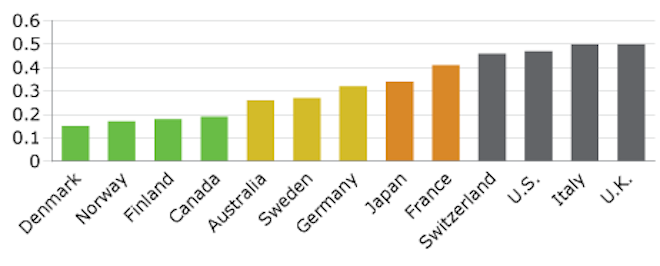

Intergenerational income mobility: Where does what your parents made matter most?

[Lower values equals more mobility.]

Source: Conference Board of Canada

Source: Conference Board of Canada

Q. So you’re afraid the conditions that created good social mobility in Canada haven’t been maintained?

A. There are long lags in these processes. We’re not very clear, now that we’ve entered this era of slower productivity growth when the benefits aren’t being equally shared, how this is all going to play out in the next decade or two.

Stephen Gordon: “Get people from the lower parts up into the middle.”

Maclean’s. Are middle incomes stagnant? That’s often the premise of political talk on this subject.

Gordon: I would try to separate the last 30 years into two very different episodes. In the first half of that period incomes weren’t stagnating, they were declining. In the 1980s and early 1990s, we had two recessions. Public finances were out of control. We had high and variable inflation. These were not good times.

Sometime around the mid-1990s, things turned around. Public finances got under control, inflation got under control, we got lucky with oil prices. And since that time incomes have increased. We haven’t recovered to the levels of 1981, but the recent trend has been positive. What is the trend that matters now? I don’t think the challenges should be defined by bad times that ended 15 years ago, they should be defined by the context now.

Q. Why is that reversal of fortune so often missed then? What’s clouding the discussion?

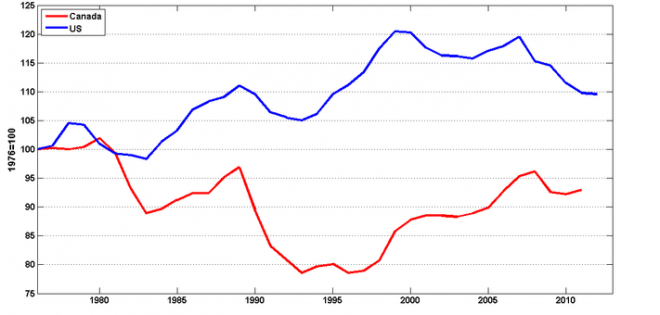

A. For some perspective, in the United States numbers came out recently about American median income. Now, what they had was incomes that rose in the 1980s and 1990s, and peaked around 1999. Since then, they have fallen. So the U.S. profile is different, an opposite shape from the Canadian one.

Canadian and U.S. real median incomes

Source: Worthwhile Canadian Initiative

Q. So do you see cause for concern anywhere in the Canadian income data?

A. There’s still concern about those in the bottom part of the income distribution falling away. We see very disturbing numbers for basic literacy levels. We see very disturbing levels of high school drop-out rates, especially among boys. The concern there is about getting people from the low into the middle. It’s very dangerous to think the middle class is being hollowed out or something. The problem isn’t that we need to pour money into the middle. It would be better to get people from the lower parts up into the middle.

Q. How do you see government programs working for middle and lower income earners?

A. Governments have started to be more focused on the middle class. Thirty years ago, median income people paid to the government $3,000 a year more, roughly, than they received in benefits. Now, it’s reversed, the median earners are net beneficiaries of $3,000 a year from various levels of government—this is not just federal.

Q. And how important are those payments from government?

A. All around the world the countries that have the most success in reducing inequality all do it through transfers.

Q. What Canadian transfers would you point to as examples of important transfers of that sort?

A. The Child Benefit—that’s money right there. The Working Income Tax Benefit. Those are the kinds of programs that work best. Give people cash. It sounds silly, but the solution to poverty: give poor people money.

Q. Just to get back to median incomes, what do you make of the argument that Canada’s recent gains has been skewed by high commodity prices? Maybe deep problems in Ontario manufacturing, say, are masked by the upbeat story in oil and gas producing provinces.

A. Let’s reverse that. If it was only Ontario that was doing well, would that mean Canada as a whole was doing better? Also, that money doesn’t all stay in Alberta. I mean, the federal government on its own, just through its taxing and spending patterns, transfers about seven per cent of Alberta’s GDP to the rest of the country.

Q. What’s wrong with the debate over the Canadian economy being dominated by the politicians’ preoccupation with middle-class voters?

A. Basically it’s about people who are below middle class and would like to become part of it. Social mobility means getting into the middle class, not just climbing up above it.