Would Enbridge’s Line 9 really save Quebec refineries $23 billion?

Andrew Leach checks the math on a very big number in the pipeline hearing

Enbridge Norman Wells Pipeline. Right of way between Norman Wells and Fort Simpson

Share

This article appeared first on CanadianBusiness.com

The National Energy Board is about to wrap-up hearings on Enbridge’s proposal to reverse the flow of one section of Line 9, an oil pipeline which now flows from Montreal, Que. to Westover, Ont. The west-to-east reversal, along with a 25% expansion in shipping capacity, would mean the pipeline could ship up to 300,000 barrels per day of crude from Sarnia, Ont. to Montreal. The project, Enbridge estimates, will save Quebec refineries $23 billion over the next 30 years. Yes, billions.

I decided to check some of the numbers on this project, as I did in a similar math-check on TransCanada’s Energy East project. Much as with Energy East, the economic case for the reversal of Line 9 is that it is expected to be cheaper for Canadian refineries to use North American crude as compared to crude imported from overseas for the foreseeable future. That wasn’t the case until recently. As pipeline infrastructure and crude oil markets adjusts to new U.S. and Canadian production and declining North American demand, more oil is moving from the mid-continent to the coast. Oil pipelines in the continent used to flow primarily to points in the Midwest, but as that area has seen increases in domestic supply as well as increased imports from Canada, it is now over-supplied with oil. As shipping infrastructure is re-aligned to ship oil out of the Great Lakes region, where oil used to trade at a premium to world prices because it had to be shipped-in from coastal markets, oil in the mid-continent will likely trade at a discount for the foreseeable future. Over time, we should expect the discount on mid-continent crude to be $3-5 per barrel plus inflation compared to world market prices, since that’s about what it would cost to ship a barrel south to the Gulf Coast. Refineries using mid-continent crude, then, are likely in for some savings. The question is whether these savings can truly amount to something as astronomical as $23 billion.

So, how does Enbridge get $23 billion? They state in one of their regulatory filings that, “the (crude cost) savings are estimated to amount to approximately $780 million annually over 30 years, based on forecast oil price differentials, throughput of 250,000 barrels per day, and deliveries divided equally between Montréal and Québec City.” Another way to look at it is average cost savings of $8.54 per barrel over the next 30 years. (Note here that Enbridge is speaking about light oil, not bitumen. Quebec refineries are geared toward processing light crude and would have to embark in a costly retooling in order to handle heavy crude from the oil sands.)

Instinctively, I was suspicious of a number as big as $23 billion. A few back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest Enbridge’s figure is at least a modest overestimation.

Refineries in Montreal and Quebec City currently rely on imported crude for which we normally use UK Brent crude as a price benchmark. On top of Brent prices, they generally have to pay a shipping charge of about $2 per barrel. For crude from the mid-continent, instead, people use a different price benchmark called West Texas Intermediate, or WTI. You could start with a simple calculation, and assume that we’d need to see WTI price discounts to Brent crude large enough to make up $8.54 per barrel in savings, plus the cost of shipping the crude from Cushing, Oklahoma (where WTI contracts are settled) to Montreal, minus the $2 in shipping costs refiners would have otherwise had to pay on Brent-based imports. To make Enbridge’s math worth with those assumptions, you’d need to expect WTI crude to be about $14 per barrel cheaper than Brent.

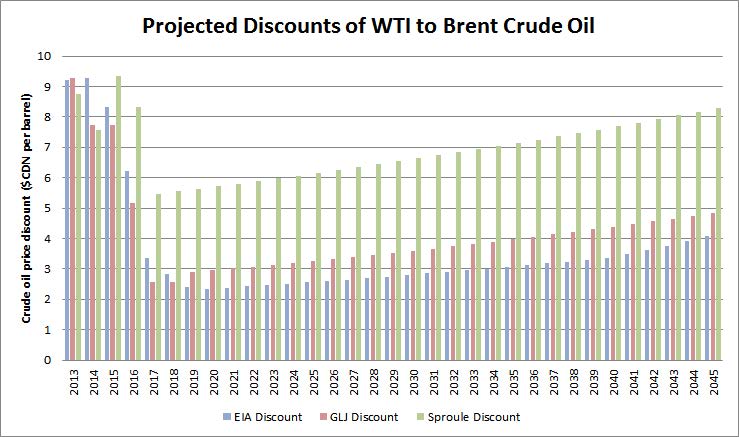

That is a lot. The chart below shows the WTI-to-Brent price discount for the next 30 years as forecasts by the U.S. Energy Information Administration (15-04-2013), Sproule Associates (09-30-13) and GLJ Petroleum Consultants (10-01-13). All projections suggest that discounts will decrease from today’s levels but remain above zero. Still, they vary widely — and no one is predicting differentials of $14 per barrel.

Does this mean Enbridge’s math doesn’t work? To understand how Line 9 might allow refiners to access lower cost crude, you need to look at oil pricing within North America in yet more detail. That requires a couple of assumptions. I am going to assume that the mid-continent crude market will see the lowest prices around the tip of Lake Michigan, from which oil is either shipped south to the oil terminal of Cushing, Oklahoma, where WTI contracts are settled, or north to Canada. If these market dynamics play out, the price of crude at the tip of Lake Michigan should be roughly equal to the WTI prices minus $3 per barrel. It’s this discount, added to the premium to Brent currently paid by Quebec refiners, that makes the savings claimed by Enbridge plausible. Oil shipped to Montreal would still face pipeline tolls to the U.S. border and onward to Montreal of about $4.50 per barrel, which means a refinery in Montreal is likely going to be looking at costs of crude of WTI plus about $1.50 per barrel with the pipeline reversal in place. So, even if WTI traded at par with Brent, refiners would still be ahead by a bit. In my scenario, the oil price differentials on the graph above are gravy.

What do the crude price forecasts used to build the graph above mean for the economics of Line 9 if my assumptions above hold? The outcomes show a broad range, but none of the three get you to Enbridge’s $23 billion figure. Using the EIA forecast, which has the narrowest future differentials, we’d expect to see crude cost savings of $10.8 billion for Quebec refineries over 30 years. The GLJ forecast is better news, with $12.4 billion in decreased crude costs. The Sproule forecast would see refineries saving $20.7 billion over 30 years — close to the figure reported by Enbridge, though still a bit lower. A reasonable quibble with both my numbers and those provided by Enbridge is that they are reported in nominal terms, simply adding up dollars over time. A net present value calculation, with a 10% rate of discount commonly used in the oil and gas industry, would lower the value of my savings calculations to $3-5 billion over 30 years. Still in the billions, just not $23 billion.

Disclosure: Readers should be aware that the author holds the Enbridge Professorship at the Alberta School of Business, University of Alberta. You can read what that means here. This post received no input from Enbridge, nor were they made aware of it being published in advance with the exception of posts made on the author’s Twitter account here and here.