Young and carless

The auto industry has yet to find a way to get young people driving again

Ford CEO Mark Fields (R) and Executive Chairman William Clay Ford, Jr. (L) speak next to a Ford GT during the company’s presentation on the first press preview day of the North American International Auto Show in Detroit, Michigan, January 12, 2015. CREDIT: Mark Blinch/Reuters

Share

Inside the packed Joe Louis Arena this week, Ford Motor Co. hit the three notes that reliably send attendees of the Detroit auto show into rapture: big, fast and cool. A new Ford F-150 Raptor, a souped-up off-road version of its bestselling pickup truck, was the first to roll out. Next, a new Mustang for track enthusiasts—lots of horsepower, no air conditioning—rumbled onto the floor. But the best was saved for last: a new Ford GT supercar concept. The low-slung racer was all giant rims and gaping air intakes, leaving executive vice-chairman Bill Ford and CEO Mark Fields giddy with excitement. “Bill, should we build it?” Fields asked, playing to the crowd. Replied Ford: “I think we should.”

To say Detroit is feeling good again is an understatement. As snow fell outside, a party heated up inside the sprawling Cobo conference centre a few steps from the arena, with free food, chatty executives and lots of vehicular eye candy. Among the highlights: new pickup trucks from Toyota and Nissan; Fiat Chrysler’s Alfa Romeo 4C Spider coupe; a curvy Mercedes GLE Coupe; and an Acura NSX supercar that will cost around $150,000. With the desperate days of the recession long gone, automakers are experiencing what amounts to automotive heaven: an improving U.S. economy alongside plummeting oil prices—all at a time when it’s never been easier for consumers to borrow cash. As a result, the industry collectively moved 16.5 million new vehicles off dealers’ lots last year, the most since 2006. In Canada, meanwhile, sales set a new record of 1.85 million. What’s more, thanks to cheap gasoline, there are predictions 2015 could be even better.

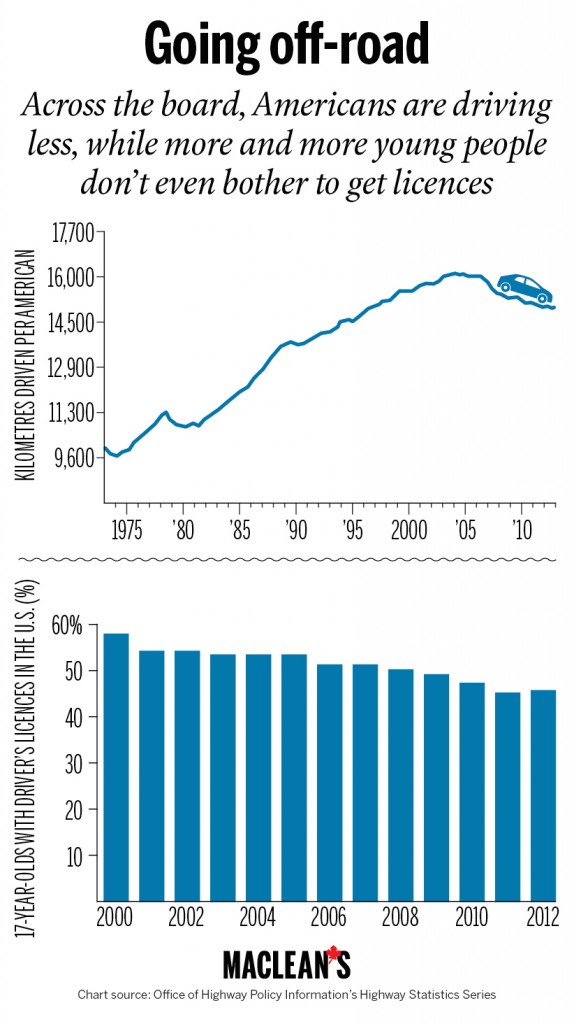

But there was at least one aspect of the industry that wasn’t being celebrated, or even much talked about: the growing number of young people who couldn’t care less about cars, regardless of their specs or styling. Indeed, several studies show many under the age of 35 don’t even bother to get their driver’s licences anymore. Why? The reasons range from the outsized impact of the recession on young people to the rising popularity of car-free urban living. But the biggest factor appears to be the absence of an emotional connection to the growl of a V6 engine or the plastic smell of new upholstery. For the Baby Boomers, who account for nearly 40 per cent of car sales, a set of wheels was a way to connect with friends and define one’s personality. But, these days, teens can just send text messages or update their Facebook profiles. “If you look at a car as a means of establishing one’s freedom, the competition has gotten much stiffer,” says Ken Wong, a marketing professor at Queen’s University.

It all amounts to a looming existential crisis for the industry, and few seem to know what to do about it. Fiat Chrysler has gone out of its way to emphasize annoying Internet memes in its Fiat 500 ads. Toyota built its entire Scion car brand around appealing to people under the age of 50. General Motors went to MTV for help. None of it has had much impact.

What all carmakers seem to agree on is that technology is a must with this crowd—be it the ability to stream iPhone playlists or dashboard apps that integrate with social media (without overly distracting drivers from the road ahead, one hopes). Yet, transforming vehicles into giant smartphones on wheels, as Toyota literally did when it unveiled a concept called the Fun-Vii in 2011, seems unlikely to convince someone to purchase a car if she wasn’t already in the market for one. And while there’s some evidence to suggest older Millennials, now approaching their early 30s, are finally venturing into dealers’ showrooms because they have families, buying a car because “now you have no choice” makes for a lousy marketing slogan.

What all carmakers seem to agree on is that technology is a must with this crowd—be it the ability to stream iPhone playlists or dashboard apps that integrate with social media (without overly distracting drivers from the road ahead, one hopes). Yet, transforming vehicles into giant smartphones on wheels, as Toyota literally did when it unveiled a concept called the Fun-Vii in 2011, seems unlikely to convince someone to purchase a car if she wasn’t already in the market for one. And while there’s some evidence to suggest older Millennials, now approaching their early 30s, are finally venturing into dealers’ showrooms because they have families, buying a car because “now you have no choice” makes for a lousy marketing slogan.

Carmakers clearly need a better approach—and soon. Without one, all the cheap gasoline in the world isn’t going to save them.

The average American, aged 16 to 34, drove nearly one-quarter fewer miles in 2009 than the same age group did back in 2001, according to a report last year by the U.S. Public Interest Research Group Education Fund and Frontier Group. While the reluctance to get behind the wheel can be partly blamed on the bad economy—a job usually provides both incentive and the means for someone to buy a vehicle—the same study also found the biggest declines in driving weren’t necessarily in regions where job losses were highest. In fact, between 2001 and 2009, per capita driving among employed 16- to 34-years-olds still dropped by 16 per cent, the study found.

The underlying reasons for young people’s automotive indifference are varied. Graduated licensing programs have made it more difficult for teens to jump behind the wheel, with only 46 per cent of 17-year-olds in the U.S. having a driver’s licence in 2012, down from 58 per cent in 2000. But, even as Millennials grow older, there’s evidence they’re increasingly bypassing the idea of car ownership altogether. A recent study out of McGill University found young people are far more likely to take public transit than other generations—a decision no doubt driven partly by cost, with youth unemployment in Canada still hovering above 13 per cent, or about double the rate for the country as a whole.

Another oft-cited reason for the growing preference to go carless is the trend toward urban living. The explosion in condominium construction across the country is predicated on the idea that buyers—one in five of whom are under the age of 35, according to the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp.—prefer to live near hip restaurants, bars and entertainment districts and to be able to walk or bike to work. A sign of the times: A new 42-storey tower in downtown Toronto recently became the first in the country to be built without a parking garage. An even bigger sign: A developer in Calgary—right in the heart of oil and gas country—is asking city council for permission to do the same.

Of course, just because condo-dwellers are less likely to own cars doesn’t mean they don’t drive at all. In recent years, car-sharing services with catchy names such as Zipcar, Modo and Car2Go have popped up across Canada, providing yet another alternative to ownership. Members reserve vehicles over the Internet for as little as an hour at a time, and claim them from parking lots scattered throughout the city by waving a card over the windshield. Similarly, private car services such as Uber have made it cheaper and easier to hail a ride.

Perhaps the biggest driver of young people’s changing attitudes—and the one carmakers should be most worried about—is how technology has replaced cars as a cultural touchstone. A Zipcar-commissioned study asked Millennials what would affect their lives the most: losing their cars, televisions, computers, or mobile phones. Only 26 per cent of 18- to 24-year-olds said their vehicles, a response that would have been unthinkable a generation ago. The sentiment, if it persists, threatens to throw automakers’ carefully crafted brands out the passenger window, if it hasn’t happened already. Not one automaker ranked in the top 10 favourite brands among Millennials, according to a recent study by U.S. digital ad agency Moosylvania. Instead, the young respondents were most enamoured by Nike, Apple, Samsung, Sony and—if you can believe it—Wal-Mart.

Three years ago, GM revealed it had partnered with a consulting division of Viacom’s MTV unit to better understand Millennials and how to appeal to them. What it found, according to GM spokeswoman Annalisa Esposito Bluhm, was that they are an incredibly connected generation that doesn’t need a car to escape the shackles of their parents. A WiFi connection is good enough. She adds, “The question then becomes: How do we create a brand identity that transcends ownership experience?”

It’s a work in progress, to say the least, but one thing that apparently doesn’t help are overly funky vehicle designs. “They don’t want something that looks youthful,” Esposito Bluhm says. “They want something that looks sophisticated and looks like luxury.” Chevy got the message loud and clear after it rolled out two small, youth-focused concept cars—the Tru and the Code—at the 2012 Detroit show. Popular car blog Jalopnik dismissed the Tru as “an egg with three doors,” while saving its most vicious criticism for the Code, which it described as “a Camaro that made love to a Mazda RX-7 that had already made love to a 1 Series that was the illegitimate child of a Dodge Neon.” Mark Reuss, GM’s head of product development, says the concepts were later shelved so the automaker could invest in other areas of its lineup.

Toyota has made similar miscalculations. It launched its youthful Scion brand in the U.S. back in 2003 (the brand launched in Canada seven years later) with a focus on spiky-haired DJs, thumping electronic music and perky little cars such as the boxy xB. Yet, despite racking up respectable sales during the first few years—a time when the Detroit Three had almost no small cars in their lineup—Scion now feels more like the high school kid who’s trying too hard. December sales in Canada totalled just 138 vehicles across five models, compared to more than 12,000 for Toyota and Lexus. Larry Hutchinson, the vice-president of sales at Toyota Canada, nevertheless defends the nameplate, saying it provides Toyota with “a place to experiment,” when it comes to wooing younger buyers.

If there’s some positive news for automakers, it’s that Millennials aren’t a monolithic group. And, as they grow older and get spouses, jobs and kids, they’re more likely to require a family hauler. A recent J.D. Power report found Millennials now account for 26 per cent of U.S. vehicle sales, beating out Gen Xers for the first time ever. And, interestingly, the carmaker that’s so far excelled at wrangling Generation Y is the same one that created most of the buzz at this year’s show by debuting vehicles most of them couldn’t purchase even if they wanted to: Ford. The company has done so, in part, by having a well-balanced lineup of vehicles, with lots of cars and smaller SUVs for those on tighter budgets. But it’s also because the automaker is now comfortable in its own skin. “It’s all about being authentic,” says Dianne Craig, president of Ford Canada, when asked why the automaker outranks its rivals when it comes to brand consideration among the group. “You have to be sincere with this audience.” And clever. Ford has partnered with car-sharing services on some U.S. college campuses in an effort to have them test-drive their vehicles without realizing it.

Technology is a key part of Ford’s soft sales pitch. Back in 2007, Ford began equipping vehicles with its Sync infotainment system, which allowed drivers to make hands-free telephone calls, stream music from their phones and perform other tasks by using voice commands. “Now that’s almost the cost of entry,” says Lisa Schoder, Ford’s global small-car marketing manager. “[Younger buyers] just assume that kind of stuff is going to work.”

Now, everyone has jumped on the bandwagon. This year, the Detroit show featured a “technology showcase” and, a week earlier, 10 automakers showed off their latest apps and safety systems at the consumer electronics show in Las Vegas, a venue that’s historically been mostly about phones and computers.

The problem, of course, is that no one is going to buy a $23,000 vehicle just because it links to his Facebook page. “It’s only a means for automakers to differentiate themselves from other car companies—and less so these days, as electronics become more pervasive,” says Wong. “I don’t know that it does anything to rekindle interest in cars.” The core problem, Wong argues, is simple economics. Owning a car has never been an attractive financial proposition, once financing, insurance, maintenance, parking and fuel are added into the equation. And now that cheaper and more convenient alternatives are emerging, it seems like only a matter of time before carmakers will have a true crisis on their hands. “If you take out the psychological benefits”—the freedom, the sex appeal—“there’s not a lot going for [the car],” Wong says.

In the near term, Wong suggests carmakers respond by offering buyers rebates for gasoline or parking—gestures that acknowledge the true cost of car ownership. Down the road, however, he argues they may need to consider a new business model entirely. “I think car companies have to stop just being suppliers of cars,” Wong says. “There’s no reason why a car company wouldn’t have a massive competitive advantage offering an Uber-type service or a car-sharing service. They may be able to put themselves in the right place at the right time, instead of trying to constantly force the consumer into thinking the time is right to buy a car.”

In the meantime, the auto industry will do what it’s always done: build fast machines that excite and delight, then flog them at raucous industry bashes like the Detroit auto show—that is, until people stop showing up at the doors.