Loblaws’ price-fixing may have cost you at least $400

Any way you slice it, Canadian bread shouldn’t have cost this much

Dollar bills in a white toaster, about to be burned. Copy space available.

Share

As word emerged about the Loblaws chain and bread-maker George Weston Ltd. confessing their role in a massive price-fixing scheme, analysts often referred to bread as a supermarket loss leader. Think of this like your favourite pub’s wing night: they lower prices to a level below what it costs to make and serve them, in hopes of getting patrons in the door and guzzling beer. Wonder Bread or Dempster’s Whole Wheat, the argument goes, would similarly be offered at cut-rate prices to bring in shoppers who will generate money for grocers in other aisles.

It’s hard for analysts to say definitively that bagged bread is a loss leader; there’s plenty that isn’t clear about the economics in Canadian grocery stores, as evidenced by the Competition Bureau’s ongoing price-fixing investigation of multiple chains and suppliers, on top of the fact the scheme Loblaws and its sister manufacturing company admitted went undetected from mid-2001 until March 2015.

READ: You can sign up for the $25 Loblaw gift card starting today. Here’s how.

Moreover, many of the price figures we can see suggest bread is the opposite of a loss leader. Rather, there are many signals and comparisons that suggest bread became a much more lucrative product for supermarkets over the 14 years in question.

As Maclean’s noted last month, from 2001 to 2015 the consumer price index for bread rose dramatically more than did the average for all food prices. In addition to tracking bread for the key inflation measure, Statistics Canada also reports the monthly average price for a loaf of bread. The loaf that cost you $1.42 in July 2001, was a $3.04 in March 2015—more than double the (ahem) dough.

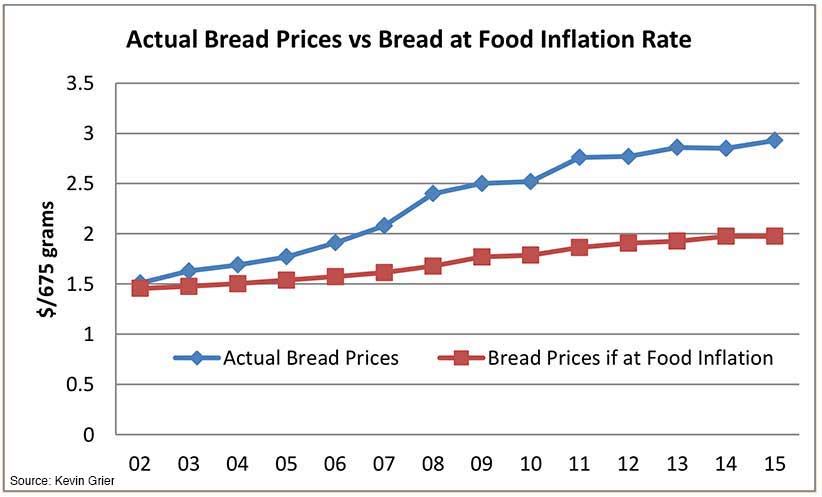

Kevin Grier, a food market analyst based in Ontario, measured what bread should have cost if it rose in tandem with overall food price inflation. By 2015, there’s a $1 gap between the real price and Grier’s price. If a family buys one bagged bread per week for a year, that’s a $52 difference—a lot when compared to the $25 gift cards Loblaws has offered as their mea-culpa for 14 years of fixing prices. The average price gap from 2002 to 2014 was 55 cents, Grier says—or that one loaf per week over that period may have plumped up a grocery bill by $371.80.

The appearance of inordinate price increases does not necessarily mean there was price fixing, Grier notes. “It raises your attention, that if they did do it, you can see it,” he says. “But it doesn’t prove that they did anything.”

READ: Where to donate your $25 Loblaws gift card: find your nearest food bank here

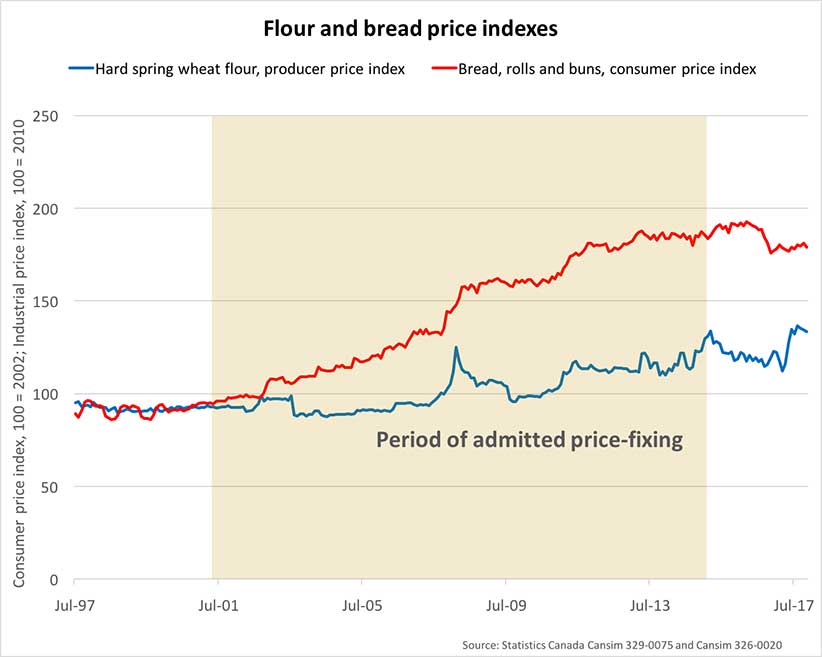

And perhaps it’s unfair to assume the bread cost should have lined up neatly with the cost of other groceries. That would discount the fluctuations in grain prices over the years, particularly with last decade’s spike in crop use as biofuel. Let’s consider the price of milled flour, using the industrial price index, and see how that compared with bread in the consumer price index.

Oh my.

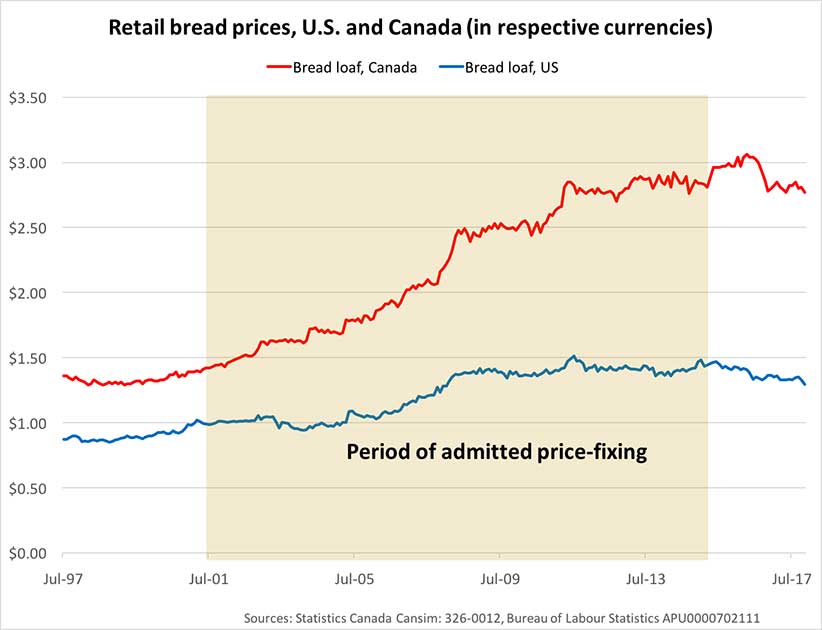

It’s equally jarring when you consider how prices for loaves in the U.S. have risen over time. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, American consumers saw bread prices rise half as fast as happened in Canada during the time of Loblaws’ misconduct.

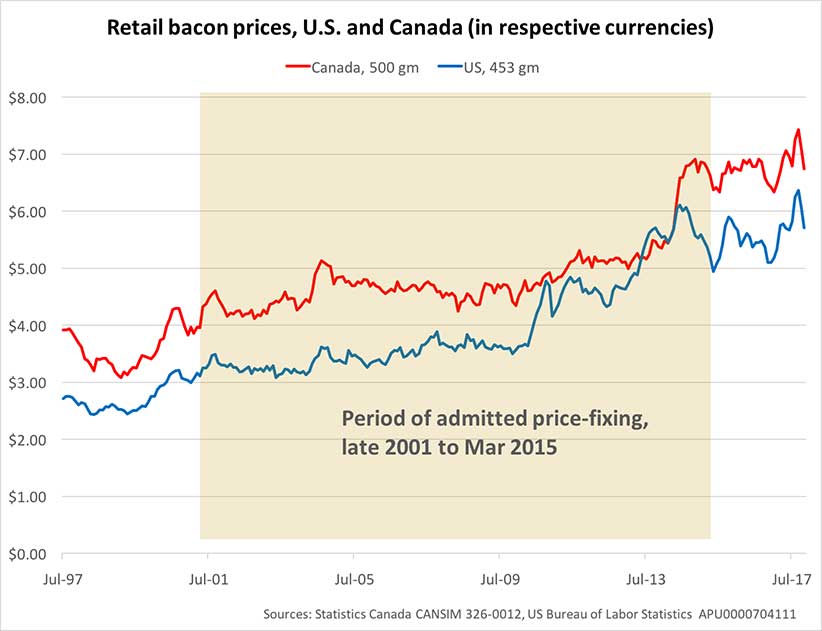

Outside of Canadian supply-managed foods like dairy and eggs, Canada and U.S. foods generally follow the same price trajectory. Here’s bacon:

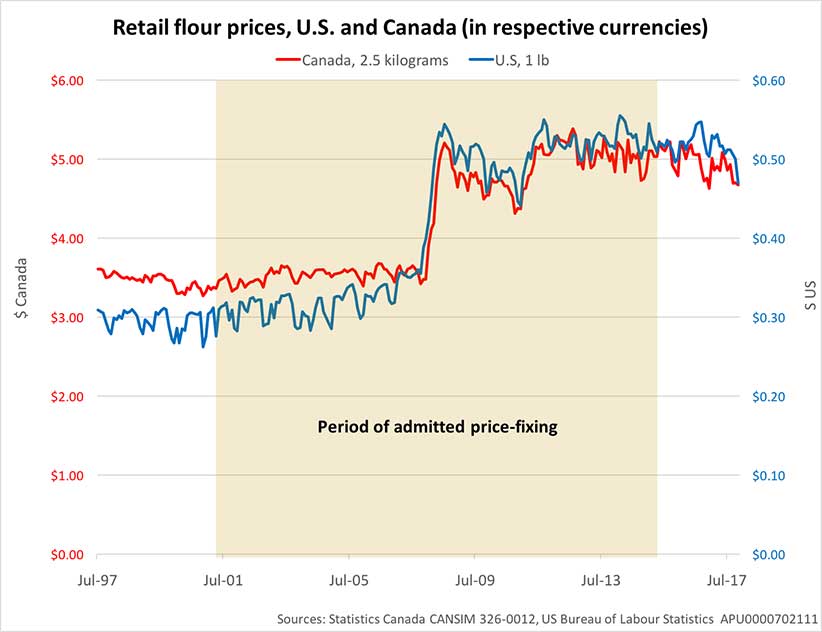

And here’s retail flour:

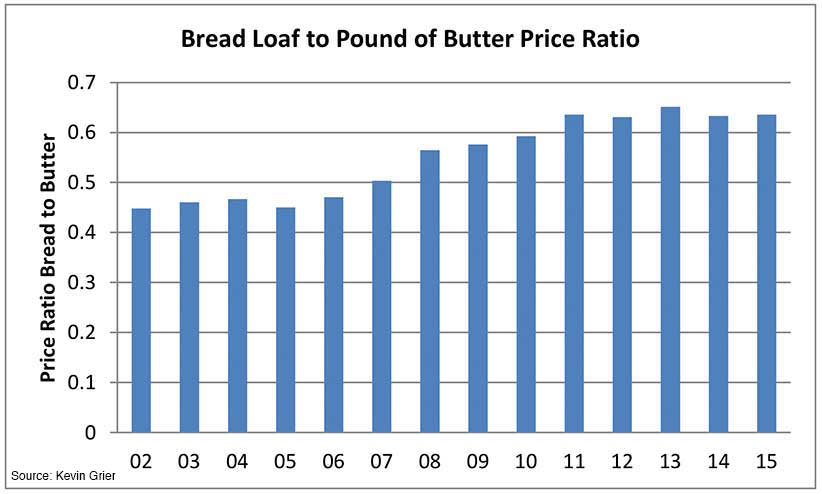

Lastly, in a note to subscribers of his market reports, Grier also looked at the price spread between bread and its most friendly spread: butter. “In 2002 a loaf of bread was valued at 45 per cent of a pound of butter,” he writes. “By 2015 bread was worth 64 per cent of a pound of butter.”

It could take years before the Competition Bureau reveals what really took place between Loblaws, Sobeys, other chains and their packaged bread suppliers. On the bright side, bread prices have stopped rising, and settled to around the same prices they were in 2011. But the past increases do seem to leave a trail of breadcrumbs for the suspicious.

MORE ABOUT LOBLAW:

- Where to donate your $25 Loblaws gift card: find your nearest food bank here

- Is price fixing a major problem in Canada?

- Loblaw could owe you much more than $25

- Canada’s Richest People 2018: The Top 25 Richest Canadians

- CIBC, PC Financial split sheds light on bruised loyalty card industry

- Let pharmacies sell medical marijuana, Loblaw president says

- Loblaw store expansion to create 20,000 jobs this year

- Just catching up? Loblaw is reversing decision to pull French’s