Are oil sands incompatible with action on climate change?

A high-profile report that claims most oil sands can’t be burned if the world hopes to prevent global warming leaves several big questions unanswered

Share

This week, a new peer-reviewed letter in top scientific journal Nature by Christophe McGlade and Paul Ekins drew a ton of media attention. This is, in part, due to the letter’s conclusions, and also due to Nature‘s first-rate ability to stir up media coverage for published work—every energy and environment writer I know had an embargoed copy of the paper in hand days before it was published. The paper generated a great deal of attention in Canada, most of it centred on a single sentence in the paper: “85 per cent of Cdn bitumen reserves remain unburnable if the 2C limit (for global temperature changes) is not to be exceeded.” The headlines across Canada reflected this: “85 per cent of oil sands can’t be burned if world to limit global warming,” read the CTV news headline. The Globe had a similar statement that, “oil sands must remain largely unexploited to meet climate target, study finds.”

I found there to be a lot of good things in this paper, but I felt that the authors and the media coverage of the paper pushed the results too far and overemphasized the role of oil sands in the overall global outcome. I also felt that there were significant pieces of the analysis missing from this paper which render it less useful than it would otherwise be for understanding energy transitions. Overall, there was plenty of good, a lot of bad, and some ugly.

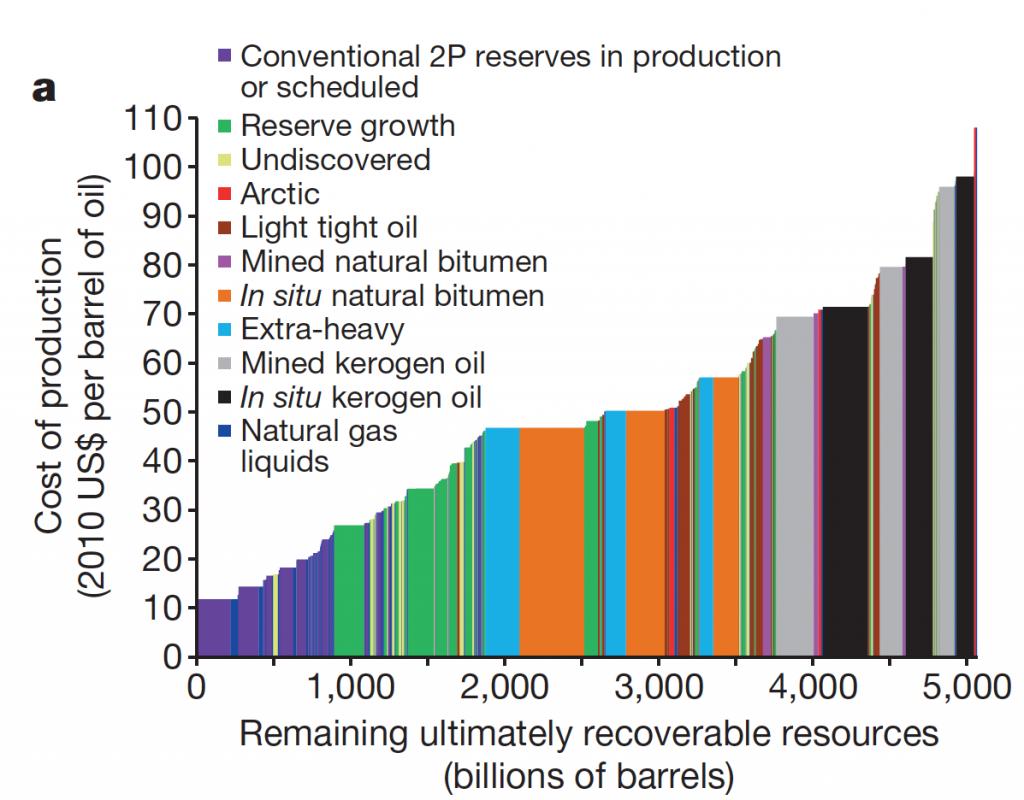

Let’s start with the good. This is exactly the type of analysis we should have, and the work done in this paper (much of it building on McGlade’s Ph.D. thesis) in terms of detailed modelling of field-level reserves and resources is very important. Shown in the figure below for oil, the authors break down global reserves and resources of oil, coal, and natural gas by cost of extraction, effectively constructing a global supply curve for energy. Resource prices, in this case for oil, along with emissions constraints, will then determine which reserves are produced, which resources eventually become reserves and which current reserves or resources remain undeveloped for economic reasons.

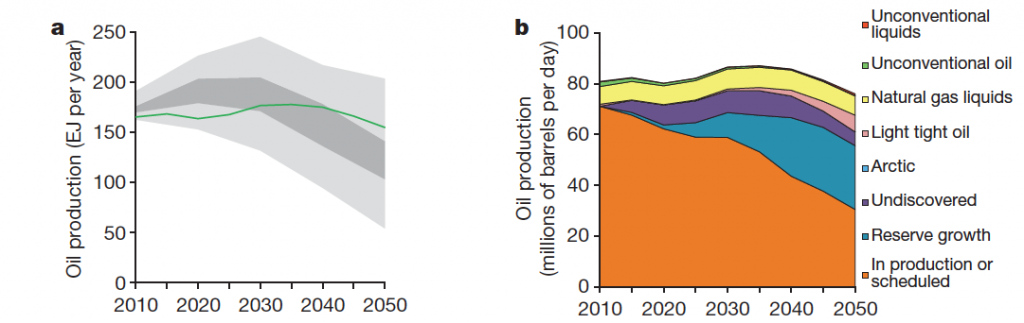

Using these supply curves, combined with a global carbon budget consistent with keeping global climate change under the two-degree Celsius limit agreed to by global leaders, the authors develop projections both for aggregate use of oil, gas, and coal as well as the use of individual oil, gas, and coal resources and reserves. This is where the controversial conclusion with respect to oil sands comes from, but more on that later. In the figure below, you can see the outcome of the McGlade and Ekins analysis with respect to oil, both in terms of total output compared to other similar analysis (they are basically middle-of-the-road here) in the left panel, and in terms of which of the fields or resource bases are used to produce this overall quantity.

The left-hand panel, in exajoules per year, is probably not a unit to which you are accustomed, but what you can see, on the right hand panel, is that the McGlade and Ekins outcome, which is a little above average for other studies which test this question, finds the oil production remains basically flat at today’s levels between now and 2050 as the world enacts aggressive climate policies. How many of you would have gotten that impression from the media coverage of the paper? Not many, I assume.

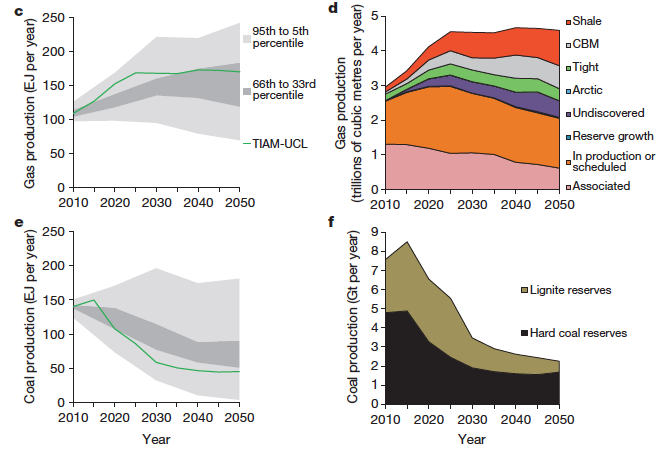

How can that be? Isn’t oil production bad for climate change? Doesn’t it lead to increased GHG emissions? Yes, on both counts. If so, why do the authors conclude that oil production would remain basically flat in response to aggressive climate change mitigation? First, flat oil production is a significant decrease compared to what we’d expect to happen without aggressive policies in place, and second, a lot of the heavy lifting in terms of climate change mitigation happens through displacement of coal while holding oil constant, not by reducing all fossil fuels by the same percentage. You can see that in the panels below, which show gas production increasing above today’s levels while coal production is cut by more than a factor of three. So, when you hear that this paper concludes, as do many other similar analyses, that two-thirds of all fossil fuel reserves need to remain in the ground to combat climate change, that doesn’t imply that two-thirds of any individual type of fossil fuel reserve, or two-thirds of any individual pool of fossil fuel needs to remain undeveloped, or that such an even distribution would be optimal.

I hope you can see from the above why this type of analysis is useful and important — it tells us a lot both about the stringency of policy required and the expected outcomes from a global carbon constraint implemented through optimal economic policy.

That’s the good — now for the bad. The McGlade and Ekins paper models outcomes from a particular policy path to reach a particular outcome, and so their model does not support many of the conclusions they’ve included in the paper including those most cited by the media. In economics, we focus a great deal on two types of conditions: sufficient conditions and necessary conditions. A sufficient condition describes an action which, if taken, would guarantee the outcome in question whereas a necessary condition says that without a particular action, the desired outcome is impossible. In their paper, McGlade and Ekins state that stranding a significant share of the oil sands resource is a necessary condition for meeting a 2° C climate change goal: “85 per cent of (Canada’s) 48 billion of barrels of bitumen reserves thus remain unburnable if the 2° C limit is not to be exceeded.” This statement is simply not supported by their results — it’s an outcome of their model, but not a necessary condition.

To see why this is not a necessary condition, look back to the first panel above. The predicted level of global oil production of approximately 75 million barrels per day in 2050 could come from a variety of sources, and whether you had 75 million barrels per day with 10 million barrels per day of oil sands production or 76.5 million barrels per day of oil production with no oil sands production and some lower emissions sources, you’d have basically the same life cycle global emissions and the same global climate change trajectory. A variety of similar substitutions could be implemented, leading to the same GHG outcome with higher oil sands production. The outcome of the model should still be seen as a clear statement of the carbon policy risk to oil sands and other fossil fuel resource value, something I’ve written about at length here, but framing an oil sands cap as a necessary condition for meeting a 2°C limit is simply not supported by the analysis. Note (added Jan 12): McGlade and Ekins acknowledge this in their paper, stating that, “other regional distributions of unburnable reserves are possible while still remaining with the 2 degrees Celsius limit (even through these would have lower social welfare.”

Had I been asked to review this paper, I would have asked for two pieces of additional information to be included in the published version: time series of resource (oil gas, and coal) and carbon prices. Without this information, it’s almost impossible to validate the field-level results which make this paper so interesting and controversial. I’ll use oil sands as an example of why, since I know this resource better than others, but it applies across the board. The authors find three principal responses in the oil sands sector:

1. “open-pit mining of natural bitumen in Canada soon drops to negligible levels after 2020 in all scenarios because it is considerably less economic than other methods of production.” McGlade and Ekins (2015)

2. “Production by in situ technologies continues in the 2 C scenario that allows CCS, but this is accompanied by a rapid and total decarbonization of the auxiliary energy inputs required.” McGlade and Ekins (2015)

3. “Cumulative production of Canadian bitumen between 2010 and 2050 is still only 7.5 billion barrels.” McGlade and Ekins (2015)

The first of these is remarkable. Today, bitumen mines account for a little less than half of the more than two million barrels per day of production from oil sands, and have operating and sustaining capital costs which are generally less than $50 per barrel of synthetic crude oil and GHG emissions per barrel of approximately 0.1 tonnes per barrel produced. To believe that all of these projects, including projects currently under development by Suncor, Imperial Oil, and Canadian Natural Resources limited would be negligible within five years suggests a combination of very low oil prices and/or very high domestic carbon prices in the very near term. Unfortunately, the paper does not provide estimates of either, so we have no way to validate this conclusion. You can back it out by looking at the resource supply curve above — most of the oil sands resource is ranked with a production cost of below $70 per barrel, so it must be the case that oil prices lie well below that, net of carbon prices, if the resource remains unused.

The second conclusion, which would see deployment of CCS and total decarbonization of inputs to in-situ oil sands production seems to conflict with the first. Yes, such a transition would be possible, but would rely on very high revenue per barrel and/or very low costs of CCS and decarbonization of natural gas production and processing. It’s hard to imagine how this would be economic in an environment in which existing, relatively low cost bitumen mines are shutting down rapidly. Again, it all comes down to oil and carbon price combinations, but we have no way to assess this as this information is not provided in the paper.

Finally, the two first results yield a third outcome that cumulative bitumen production between 2010 and 2050 is 7.5 billion barrels. Between 2010 and 2014, Alberta produced 3.5 billion barrels of bitumen, and so the paper predicts bitumen production equivalent to that currently forecast between now and 2018, and that’s it. It implies a shut-in of all current projects within the next three years. When I was first asked to comment for Margaret Munro’s piece on the result that 85 per cent of Alberta’s bitumen reserves would remain in the ground, it didn’t seem that far-fetched, but I was making calculations based on the current Alberta reserves number of 168 billion barrels — it’s about what you’d expect if we didn’t develop any new oil sands projects, and let existing projects run their course — but I’d missed that the paper analysis was based on a much lower reserves figure. Surely, the conclusion that oil sands projects including some with production costs well under $20 per barrel would be shut-in within the next five years begs the question of why, and the answer to that question is not in the paper. In interviews I saw, the authors justified this only with economics. Well, my economic analysis doesn’t allow me to understand these results.

The price is also important for understanding the sensitivity of the results on particular resource bases to the rest of the assumptions in the paper. The structure of the paper is such that, for small increases in oil prices, you would see large increases in oil sands production even with the same carbon constraint, likely offset by less coal and more gas and renewable power. At an oil price of $60 per barrel, the cost curve shown above would predict that almost all in situ oil sands resources are viable — how far from that outcome is the price outcome in the model? A small increase in price could be the difference between 15 per cent and a substantially greater share of oil sands reserves being produced under optimal climate policy. Don’t believe me? Just ask McGlade and Ekins.

In a similar analysis published last year, the authors of this week’s Nature letter found the potential for substantially more oil sands production (4.1 million barrels per day) under a low-carbon scenario using the same model as used in their Nature paper. Their results in this alternative analysis state that, “production from new bitumen projects (both mined and in situ) increases steadily for the remainder of the model horizon. By 2035 production of bitumen reaches 4.1 mb/d, up from 1.4 mb/d in 2010, with total production from all sources almost 6 mb/d.” That’s a big difference from the current study, and I think shows two things. First, that oil sands is on the margin, so we’re going to see a wide range of predictions, and second that the future technical potential for oil sands is poorly understood, and so model assumptions will vary widely and matter a lot. I expect that many of those applauding McGlade and Ekins today as having proved that oil sands are not viable under climate policy would have been slightly more suspicious of their conclusion a year ago that oil sands production could be better than carbon neutral in short order: “There is a rapid de-carbonisation of energy inputs: within a 10 year time-frame the emissions intensity drops from around 100 kgCO2/ barrel of synthetic crude to -130 kgCO2/barrel.” Yes, that’s a negative number.

So, what should you take away from this paper? First, you should applaud the fact that rather than employing black-box models of resources, that the authors have worked to build much more disaggregation in to their model. Second, you should also acknowledge that yes, if we implement more stringent carbon policy, this will change the economics of resource development and will necessarily imply that a substantial share of reserves now booked by major, publicly traded companies will never be produced. Third, you should want to know the impacts of these policies on Canada, Canadian companies, and Canadian resources and be happy that the authors try to break that down. With that in mind, however, you have to respect the spirit of scientific inquiry, which is that conclusions and analysis must be challenged to be improved, and that key factors driving results must be clear in order for that to happen. From what I can see, there are significant questions with respect to field-level responses in the oil sands sector in the McGlade and Ekins model, and I also feel they’ve overreached in attaching necessary conditions to oil sands production declines found in their results. Further, when considered against their recent results with respect to the oil sands published a year ago, we should have serious questions about the margins of error of their predictions. Unfortunately, the letter in Nature and the media coverage which followed didn’t really reflect much uncertainty.