Blocking pipelines is a costly way to lower emissions

Rather than block pipelines, we could achieve the same reduction in global emissions, but without the economic costs, by putting a price on carbon

People protest against the proposed Kinder Morgan pipeline outside Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s office, below Parliament Hill on November 21, 2016. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Fred Chartrand

Share

In the coming days and weeks, Canada’s federal government will decide the fate of many pipeline projects. First will be Northern Gateway and Enbridge’s Line 3 (due this week). Next up is Kinder Morgan’s TransMountain expansion (due by Dec. 19). The latter may face the most vocal opposition of all. Vancouver Mayor Gregor Robertson, for example, warns of protests “like we’ve never seen” and Green Leader Elizabeth May predicts a “hell-raising” that will “shake the foundation of Parliament” if the project is approved.

While there are many concerns—spill risks, Aboriginal land claims, and so on—the dominant source of opposition seems to be climate-related, especially the additional oil sands production that new pipelines would bring. “Real climate leaders don’t build pipelines,” claimed a group that recently occupied Natural Resources Minister Jim Carr’s constituency office.

But how effective is blocking pipelines at lowering emissions? And how costly? These critical questions are rarely explored. In what follows, I’ll try to provide some (admittedly rough) answers.

Effect on price and production

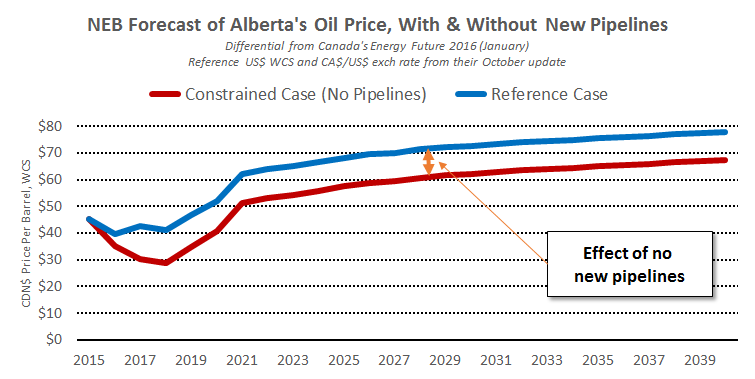

Without new pipelines, more oil would be shipped by rail. This is a more expensive option, and would contribute to lower prices for Alberta producers. Though it’s difficult to know precisely how much lower, there are estimates. In their recent Energy Future report, the National Energy Board supposes $9 to $10 per barrel is lost without any new pipelines.

But estimates vary. A few years ago, IHS (a leading energy consultancy), for example, expected the effect is closer to $5 to $6 per barrel (in U.S. dollars). In more recent analysis, they forecast the price differential grow by between $9 to $20 per barrel without pipelines, depending on how many projects go ahead and how much rail is used. In what follows, I’ll presume the effect is $10 per barrel (in Canadian dollars).

Next, the less that Alberta producers receive, the less likely they are to build new projects, and so oil production is lower than it otherwise would be. The NEB estimates that by the middle of the next decade, absent new pipelines, Alberta oil production may be roughly 10 per cent lower than otherwise.

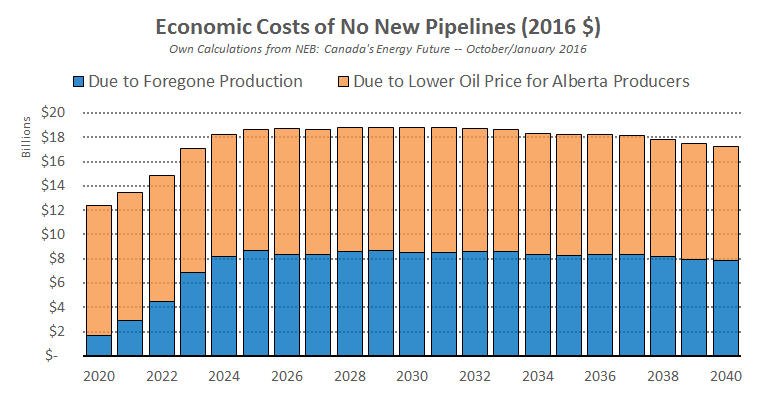

Of course, lower production is precisely what opponents of pipelines want; but it comes at a cost. And the higher the oil price is, the greater the cost. Based on NEB price forecasts, and the above data, I find losses exceed $18 billion per year by 2025. Just under half is due to forgone production, and the rest from a larger price discount. (I’ve adjusted for inflation, and denote everything in Canadian dollars.)

$18 billion is certainly an eye-popping number, but the more relevant question is: how costly is blocking pipelines per tonne of avoided emissions?

Effect on emissions

No new pipelines means less production, and less production means lower emissions. How large this effect is depends on the emissions intensity of oil sands production and on how much other sources of oil production increase to fill the gap.

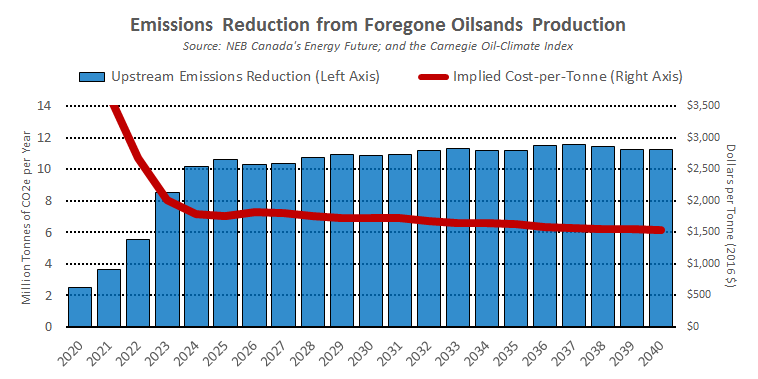

Based on recent emissions data from Environment Canada and production data from the NEB, the average in-situ oil sands emissions are about 65 kg of CO2-equivalent per barrel. Some are even better. The Cenovus Foster Creek facility, for example, is closer to 50 kg of CO2 per barrel. To be conservative, I apply the 0.065t/bbl estimate as the intensity of forgone production.

So if production is about 450,000 barrels per day lower than otherwise, then upstream emissions are nearly 10-11 million tonnes (MT) lower per year. Sounds like a lot, but at an economic cost of $18 billion, that’s well over $1,500 per tonne. Here’s the breakdown by year (in inflation adjusted 2016 dollars), which shows that blocking pipelines results in a per tonne cost of emissions avoided of between $1,500 and $2,000 per tonne. A massive cost.

But these are just upstream emissions, and they ignore the effect that oil sands production might have on total fossil fuels burned in the world.

Will we drive fewer cars if the oil sands produce less oil? Will oil production elsewhere in the world increase as ours declines? The answers depend on what happens to the world price of oil. If that price goes up, oil consumption will fall (since demand curves are downward sloping). But while less oil sands production may mean the price of oil globally will rise, it is not a sure thing. Indeed, the NEB presumes the world price of oil is unchanged whether we build more pipelines or not. (This makes sense if oil production elsewhere fills in the gap one-for-one as oil sands production falls, or if we think of OPEC as a price setter.)

But other forecasts disagree. A recent piece in Nature: Climate Change suggests each barrel of forgone oilsands production lowers global consumption by 0.6 barrels, with 0.4 barrels replaced by producers elsewhere in the world. (Although this estimate is highly sensitive to a number of parameters, and the overall methodology was soundly critiqued by Andrew Leach.)

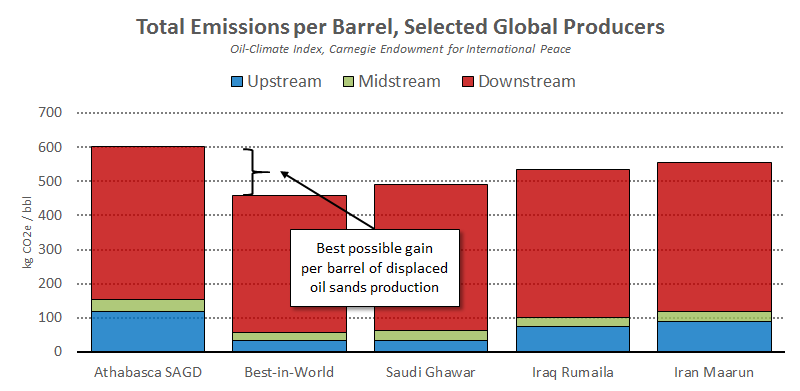

Without hanging our hat on any particular estimate, we can examine the total effect on global emissions from lower oil sands production. But we first need a broader measure of emissions. In particular, we should look at the full “well-to-wheels” emissions from various sources. Perhaps the latest, most comprehensive, and highest quality source of data on this is the Oil-Climate Index, produced by a team of researchers—including Joule Bergerson of the University of Calgary. Here’s a selection of their estimates:

(I’m presuming Athabasca SAGD production is representative of the displaced units of oil sands production, but this is likely an overestimate since newer facilities have lower emissions intensity.)

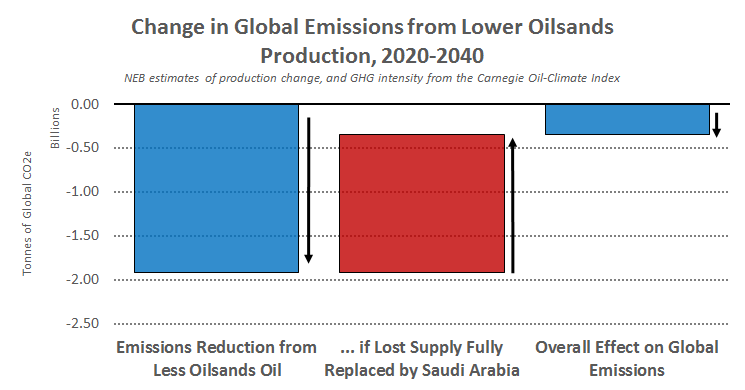

So, if oil sands production is fully replaced by oil from Saudi Arabia (which has much spare capacity), then global emissions would fall by 110 kg per barrel displaced. If none of Alberta’s forgone production is replaced by others, then emissions would fall by 601 kg per barrel (the full well-to-wheels emissions from Athabasca SAGD). So the total change in global emissions depends crucially on how much forgone Alberta production is replaced, and by what. That is, it depends on the size of the red bar below:

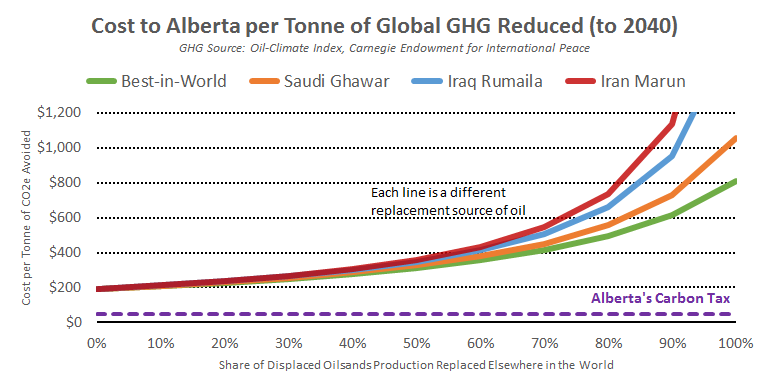

But as Alberta bears the economic costs of no new pipelines, we should estimate the implied cost to Alberta per tonne of global emissions avoided under various scenarios. I plot them below, which represents the total economic costs of emissions avoided over the 2020-40 period. From left to right along the horizontal axis are various assumptions about how much of the lower oil sands production is replaced elsewhere. Each coloured line is a different alternative producer (orange is Saudi Arabia). Under all scenarios, the costs to Alberta’s economy from lost production and a lower price are the same but as you move to the right, you get less global emissions reductions for that cost—thus, a larger cost-per-tonne.

Notice that even in the best (but laughably implausible) case, where each barrel of forgone oilsands production translates one-for-one into lower global consumption, and is replaced by no other producer anywhere, the implied costs are still nearly $200 per barrel! If forgone Alberta production is fully replaced by increased Saudi production, then the implied cost to Albertans per tonne of global GHG emissions avoided is over $1,000.

Blocking pipelines is therefore a very expensive means of lowering emissions, and far above the likely damages from a tonne of GHG emissions. Note also that this analysis abstracts from many other important dimensions. Per kilometre, transporting oil by rail is roughly twice as emissions intensive as pipelines. Rail may also have greater spill risks (though we need better data).

Comparison to carbon pricing

If we wanted to lower global emissions by the same amount as achieved by blocking all future Alberta export pipelines, we could do so more cheaply by putting a price on carbon. Of course, Alberta does and Alberta’s carbon pricing plan also provides a nice way to illustrate the difference in economic costs.

The government estimates the economic consequence of the province’s Climate Leadership Plan to be between 0.3-0.4 per cent of GDP by 2022—equivalent to roughly $1 billion per year. Applying the higher 0.4 per cent estimate to a simple projection of Alberta’s real GDP to 2030 implies a total cost of about $20 billion in economic costs (adjusting for inflation). As a result of pricing carbon, emissions may fall by about 375 MT over that same period (see page 40-41 of the Leach Report). Together, this implies an average cost-per-tonne of just over $50. That’s an order of magnitude or two smaller than blocking pipelines!!

Here’s another way to see it. Using the NEB forecast and 0.065t/bbl emissions intensity from earlier, blocking pipelines may lower upstream emissions by about 100 MT through to 2030 from lower production, with an associated economic cost of $210 billion. Alberta’s carbon pricing plan therefore achieves three to four times more reduction in Alberta emissions, at only 10 per cent the total cost. (To be sure, this is a back-of-the-envelope estimate. But the differences are so stark that it is hard to see how the general result wouldn’t hold under more rigorous analysis. It’s also worth noting the cost-effectiveness of Alberta’s plan is aided substantially by providing offsetting support to large emitters. Absent those, the costs would be higher.)

Concluding thoughts

Climate change is a critical issue. We must examine solutions with evidence and a hard head. It’s easy to target pipelines because they are visible, and the resulting economic costs are hard to see directly. In contrast, a carbon tax has highly salient costs but largely unseen (though no less real) effects on emissions. But from the perspective of global climate change, a tonne is a tonne is a tonne. Rather than incur unnecessary economic costs by blocking future pipelines, we should strive for efficient policy instead.