Is there an economic case for more infrastructure spending?

Kevin Milligan on what economists are thinking about when politicians promise investment in infrastructure

Liberal leader Justin Trudeau greets apprentices while touring a crane operator training facility Thursday, August 27, 2015 in Oakville, Ont. (Paul Chiasson/CP)

Share

Looking at the 2015 election platforms, political aspirants seem to be falling over each other to spend more on infrastructure. The Conservatives started things off in May’s budget, with a pledge to increase infrastructure spending by $750 million a year, starting in 2017-18. The Liberals have now announced a major expansion on top of the May budget plan. The NDP has promised a $1.5-billion increase by the end of a mandate, funded by a gas tax transfer. Not to be outdone, the Green party promises a “massive” increase in funding for transit and infrastructure. This political consensus is echoed by a number of think tanks and organizations across the spectrum, from the Canada West Foundation and the Chamber of Commerce to Canada 2020 and the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

[widgets_on_pages id=”Election”]

But what do economists really think about infrastructure investment in today’s context? Last year, here on Econowatch, Stephen Gordon expressed some skepticism, while I explored David Dodge’s pro-infrastructure position. Below, I’ve put together a deeper dive into the motivations and criticisms of the infrastructure proposals, with six questions an economist would consider when thinking about infrastructure.

1) Can infrastructure spending fight off a recession?

The economy is not doing well right now—if not in full recession, we are certainly in a slowdown. Some economists argue this is a great time to push against these downward trends with some countercyclical fiscal policy. See, for example, Kevin Lynch writing recently in the Globe and Mail that infrastructure spending should play this fiscal policy role.

However, other economists argue that this particular commodity-driven economic situation demands a different approach. Stephen Gordon in the National Post explains that expansionary government spending is the wrong choice for a recession driven by commodity price changes. He posits that lower commodity prices effectively lower productivity, meaning we have a supply-side shock rather than an aggregate-demand deficiency. Moreover, given we have an open trading economy and a flexible exchange rate, the effectiveness of fiscal policy is muted.

To this, I would add that a general infrastructure program is unlikely to hit the weak parts of the economy, either in time (it will take years to get new projects going), or in space (help is needed in oil-producing provinces). Taken together, I find the cyclical case for infrastructure spending to be much less than convincing, given today’s circumstances.

2) Can the federal budget afford more infrastructure spending?

As always, the question of affordability comes down to priorities. Almost anything can be afforded if taxes are sufficient and other spending is kept in check so a particular budget balance can be obtained. But what if the budget balance goes negative?

The Liberals revealed that their plans may push the federal deficit toward $10 billion for two years. In the context of our $2-trillion economy, this amounts to 0.5 per cent of GDP. To gauge the sustainability of deficits, economists typically turn to the debt-to-GDP ratio, which relates the size of the debt to our ability to pay. As long as the annual deficit stays belong the long-run growth trend, the debt-to-GDP ratio shrinks. In those terms, a 0.5 per cent of GDP deficit is small potatoes and has virtually no impact on the long-run sustainability of our public finances.

For the other parties, they’ve committed to making their infrastructure investments while maintaining a balanced budget.

3) Do public infrastructure projects pay sufficient returns?

Public infrastructure investments pay off in many ways. A volume of academic research finds public infrastructure makes workers and firms more productive. In addition, philosopher Joseph Heath argues that the impact of improved public infrastructure on quality of life is large and underappreciated.

Whatever the potential return on public investments, it only makes sense to go ahead with the investment if the return exceeds the cost of financing the investment. Which brings us to the important questions of interest rates.

4) Do interest rates affect the affordability of projects?

In basic finance classes, students learn that the decision to go ahead with a project depends on a comparison of a project’s internal rate of return with the cost of funds (sometimes called the “hurdle rate“). As the government’s borrowing costs are currently at historic lows, more projects should now exceed the hurdle rate and get a financial thumbs up.

This argument for expanding public infrastructure spending—even if it means taking on some debt—has come from some surprising places. Last year, 1990s deficit-slayer David Dodge laid out the economic case for borrowing for infrastructure in today’s low-rate environment. Going further, Larry Summers was one of the architects of the U.S. budget balance in the 1990s, yet he argues that public infrastructure investment is a “free lunch” because it expands our economic capacity at a low price.

Some commentators continue to recite the 1990s arguments about debt and deficit. In my view, we need to choose a policy that is right for our current situation, and not get stuck in justifications from the very different 1990s era of high interest rates and large structural fiscal deficits.

5) Are we already investing enough in infrastructure?

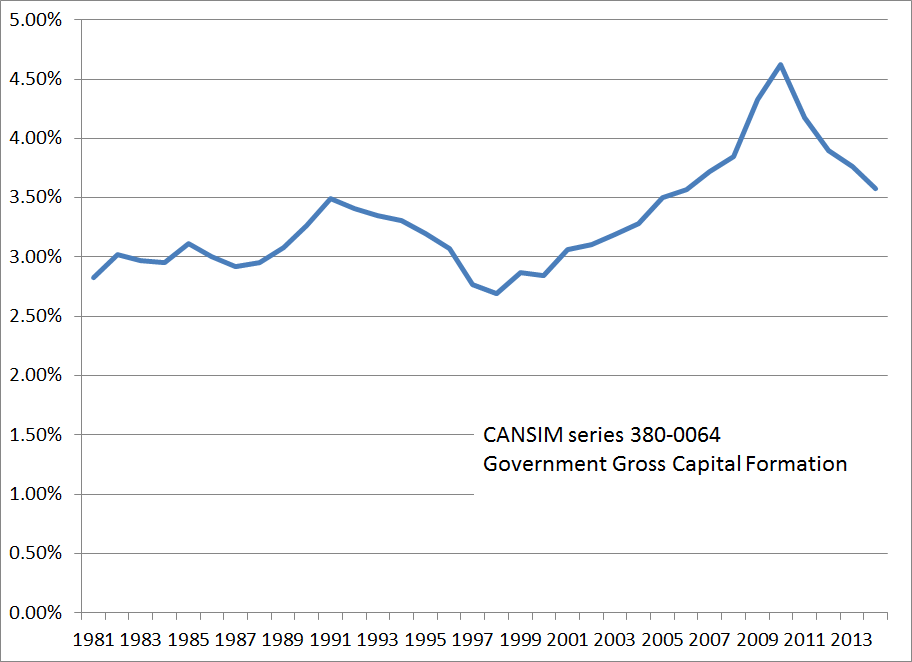

It’s useful to look at the time series of public infrastructure spending to get a sense of where we are. The chart shows that, between 1981 and the onset of the financial crisis in 2008, government infrastructure investment bounced around three per cent per year. In response to the need for fiscal stimulus, Canada ramped up infrastructure spending until 2010. After that point, we fell back in the same range for investment we saw in previous decades.

If we take the Dodge-Summers argument seriously, we should be investing much more today than we were in the 1980s and 1990s.

6) Should the federal government be doing this?

Economists like Jack Mintz have argued that the federal government ought to leave it to the provinces to choose and finance infrastructure projects, in order to ensure fiscal transparency about who is paying for what. Fiscal transparency is good, and I’ve always believed that Canada’s decentralized fiscal federation is an institutional strength, rather than something to be cast aside when inconvenient. However, a couple of offsetting arguments should also be considered.

First, local infrastructure can have national consequences. One of my favourite driving shortcuts takes me along Low Level Road in North Vancouver, alongside massive elevators filled with resources bound for foreign shores. Ports like Vancouver’s serve as national infrastructure, shipping out goods such as Saskatchewan potash and prairie-grown wheat, durum, and canola. A federal government can properly account for the national spillovers and externalities of these facilities better than lower orders of government can.

Second, the Parliamentary Budget Officer’s annual Fiscal Sustainability Report shows an increasing long-run fiscal imbalance between the federal and provincial governments. With the federal government taking on some more of the financial load for infrastructure, the fiscal burden of the provinces is somewhat lightened.

Taking this all together, what should the next government do? That depends on how the six factors above are weighted, of course. But, it seems clear that a fairly strong economic case can be made for increasing the federal government’s role in infrastructure projects.

Kevin Milligan has contributed to policy discussions with officials from all three major parties, most recently as an outside economic adviser to Liberal Leader Justin Trudeau. A full disclosure statement is here.