Not-so-great budget expectations

Jason Kirby on Stephen Harper and the political perils of a surplus

photo illustration by sarah mackinnon

Share

Smart leaders know the first lesson in managing expectations: Under-promise, over-deliver. That’s not always easy when you’re a politician who likes to throw around commitments to voters like candy to children at a Christmas parade. But, last week, Prime Minister Stephen Harper did his darndest to dampen expectations about an imminent return to surplus for Canada’s finances. He did have good news to deliver at a business event in suburban Toronto: The budget deficit for fiscal 2013-14 would be way lower than first thought. But, he cautioned, “We continue to intend to run a small deficit this year before returning to surplus.”

On Monday, the Department of Finance put out its final report for the last fiscal year, confirming what Harper had said. Rather than the $16-billion budget deficit originally forecast, the red ink added up to $5.2 billion, thanks to a boost in revenue from one-time income tax gains, asset sales and foreign-exchange gains, as well as lower program spending. The official forecast for this fiscal year (which ends next March) is for another small deficit of $2.9 billion.

Well, the economists at Toronto-Dominion Bank beg to differ. In a new report released this week, TD Economics said Canada will post a $5-billion surplus this fiscal year, and every year for the next five years, nearly tripling to $13.3 billion by 2018-19.

Part of Harper’s reticence in acknowledging the surplus that’s right in front of his face is that he’d rather save the big reveal for the annual fall economic update, which is expected to happen in late October or early November. It will kick off the Conservatives’ 2015 election campaign, replete with promises of tax breaks and other goodies for Canadians. Besides, acknowledging that Canada is in a surplus now would also mean Harper had not lived up to his 2011 election promises, such as income-splitting for families with dependent children under 18, and boosting the limit on Tax-Free Savings Accounts to $10,000 (the current cap is $5,500), because those commitments were dependent on a balanced budget—which, in effect, we have.

But Harper must also be wary of the throng of interest groups that has already gathered to offer advice for how to spend the dough.They generally fall into one of three camps: those who want program spending ramped up; those who want the money returned to taxpayers; and those who would prefer the surplus go to lowering the national debt, which now stands at $682 billion, up from $524 billion when Harper took office. The expectation in many corners is that there will be more than enough lucre to go around.

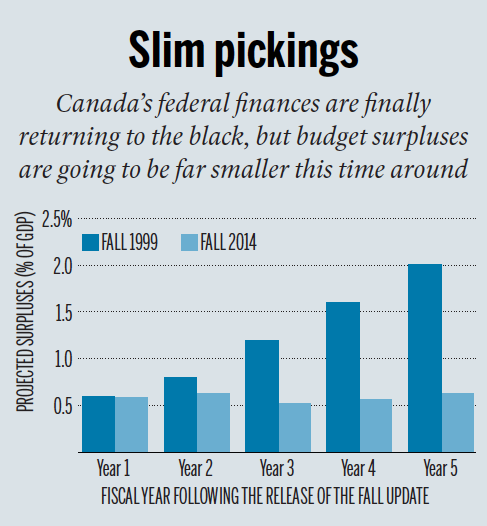

Which brings us back to that TD Economics report. Remember those juicy surpluses stretched out as far as the eye can see? There’s a big catch. Relative to the size of the economy, the forecasted surpluses aren’t that impressive at all—just 0.6 per cent each year for the next five years. To put this in perspective, the economists compared this scenario to the fiscal projections spelled out in the 1999 update. Thanks to a roaring economy, falling interest rates and shrinking debt, Ottawa’s budget surplus was projected to rise steadily to two per cent of GDP over the ensuing five years.

Looking back at the government’s expectations in 1999 is an interesting exercise, because we can contrast that with how things turned out. The dot-com crash, terror attacks and a U.S. recession to come would crimp Ottawa’s finances, yet, relative to GDP, the federal surplus still managed to hit 1.8 per cent in 2001 and remained at 0.6 per cent or higher through the next few years. As the TD report points out, between 2000 and 2005, the government was able to reduce the debt by $45 billion, implement tax-cut measures worth $85 billion and boost spending and transfers by at least $26 billion. In contrast, Ottawa today is looking at a cumulative surplus over the next five years of just $51 billion in total. Implementing Harper’s 2011 election promises would gobble up $46.3 billion. Presumably, he’ll want to update and sweeten the pot for the 2015 campaign, depending on how far back in the polls he finds himself.

When you’re dealing with a prolonged annual budget surplus of just 0.6 per cent of GDP, it wouldn’t take much to knock even the most committed deficit-slayer off course. And, contrary to the sunshine-and-roses economic narrative the Conservatives keep trotting out, things are not going well. Warnings of a recession in Europe are mounting. Slumping oil prices are crippling Canada’s exports. Employment growth has stagnated.

No wonder Harper wants to keep expectations down.