The comedy, tragedy and drama of the crisis in Greece

“What is going on with Greece?” is a question many Canadians are asking. It’s a question Greeks are asking themselves, too.

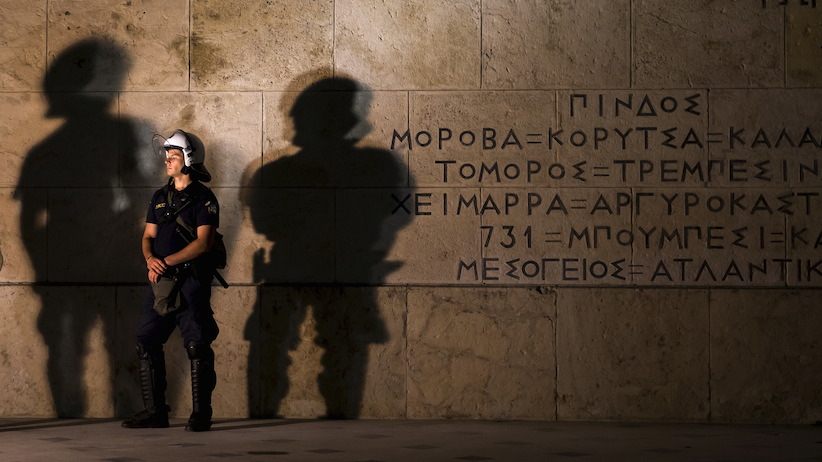

A riot police officer stands guard in front of the parliament building during an anti-austerity rally in Athens, Greece, June 29, 2015. REUTERS/Marko Djurica – RTX1IBNM

Share

“What is going on with Greece?” is a question many Canadians are asking. It’s a question Greeks are constantly asking themselves. It’s a question that, right now, could lead to several answers, including Greece leaving the European Union.

So how did it come to this? And what may happen next?

Act 1: Comedy (okay, pretty dark comedy)

Greeks love theatre. Satire, good-natured name calling and over-the-top conspiracy theories tipping towards the absurd are common fare.

I lived in Greece in 2001, the year the drachma was replaced by the Euro. At that time there were Greeks who enjoyed the idea that they had pulled a fast one, gaining entry into an exclusive club called the “Eurozone” that marked their coming of age as an advanced democracy. There was also the feeling that Greece was finally getting its due for having survived the Ottoman Empire, invasion and dictatorship.

Greeks gave up their national currency in exchange for a common currency with many EU member states including France, Germany and the rich Benelux countries. There were others who said that joining the other European powers in a currency union would never work. In their view, Greece would always be treated as a second-class citizen, or at worst be occupied by economic forces rather than military ones.

Economists had another way of describing how Greece entered the Eurozone. The former European Central Bank Chief Economist, Otmar Issing, has said, “Greece cheated to get in.” At the time Greece entered the Eurozone, it had reported a budget deficit of about one per cent of gross domestic product (GDP), which was well inside the acceptable limit of three per cent. Reports by the European powers that oversee budgets now say that Greece’s deficit wasn’t inside the three per cent limit when it joined, nor any year since. Total debt levels were also fudged.

So how did Greece’s debt manage to pile up if the books were so bad?

Simply put, lenders knew the risks of lending were spread out across the Eurozone. Borrowing costs plummeted, and the government took on additional debt. Lenders counted on fiscal discipline to be imposed by the European Central Bank and other Eurozone members.

That faith in the Eurozone institutions now seems woefully misplaced. The farce is that nothing serious happened for a long time. Fines or other sanctions did not materialize. Germany and France even joined Greece in thumbing their nose at the European Commission—essentially the Ministry of Finance for the Eurozone—when they and other member states approved an easing of the EU anti-debt rules.

Meanwhile, on the domestic front, ruses to avoid paying taxes continued. The underground economy in Greece has been estimated at upwards of 25 per cent of GDP. To put that in perspective, a recently released Statistics Canada report estimated that the underground economy in Canada is about 2.3 per cent of GDP. More importantly, Canadians have a culture of paying taxes. Sure, the plumber may ask for cash for a small job, but in Greece I was routinely asked to pay for basic services, even medical appointments, up front and in cash with no receipts.

Yes the Greeks are hard-working and entrepreneurial. They even invented Uber before there was an app – ride-sharing has long been common in Athens (something I only discovered on my first trip when additional passengers jumped in to the car, after loud haggling with the driver).

Still, the revenue implications of one-quarter of economic activity taking place with no taxation to pay for supporting infrastructure, schooling and health are enormous. Government and business leaders knew tax evasion was only funny in the short-run.

Act 2: Tragedy

When the global financial crisis hit in 2008, and the global economy stagnated, Greece was hit hard. Credit dried up. Greece found it difficult to issue and roll over its debt. And it wasn’t alone—Ireland, Spain and Italy had similar challenges.

The EU and the IMF stepped in to lend them funding, and also demanded that Greece finally address its spending. For some, including the German press, this was the day of reckoning Greece always should have counted upon. For others, austerity policies were designed to drive down confidence and growth and trap Greece in a negative cycle.

There is a bit of truth in both of these opinions. The real tragedy, however, has played itself out in the daily lives of Greeks. Social services and spending were cut to qualify for further loans. Greeks, always industrious, have had to work longer hours for less pay. Emigration has soared. Youth unemployment went from 20 per cent to 50 per cent between 2008 and 2015.

Those who could moved assets abroad. JP Morgan has estimated that only €15 billion of €410 billion in total “aid” to Greece went into the economy; the rest went to creditors.

Ireland got back on solid footing thanks, in large part, to foreign investment due to low taxes and an English-speaking population able to take on service jobs for multi-national corporations. Still, many families face high debt levels from mortgages that remain on their personal balance sheets. Financial stress is a way of life in Dublin, but there is hope.

In Greece, the adjustment to private sector activity and higher-value economic activity and jobs has not materialized. Depression set in, hitting the young population especially hard. Older Greeks have been here before. As one friend told me this weekend, his grandmother said he would only now realize why she had buried cash on their family farm.

Act 3: Drama

Greeks are outspoken, something I have always admired about their culture. Debates have raged over the possibility of a “Grexit”—Greece exiting the Euro and re-instating the old national currency. This would be sure to lead to rapid devaluation of the drachma, inflation and further capital flight. Control over monetary and economic policy would come, but at a high price.

Recent experiences, such as Latvia’s exit from the USSR and the break-up of the former Yugoslavia, show that recovery after a currency break-up is hard, but possible.

Another option is for creditors, including many fellow EU nations, to take a haircut on the debt they are owed, or even forgive it. This may be manageable in economic terms for some, but not politically. For others, including Italy, a Greek default would cause their national debt to soar in to difficult territory and could cause their own debt markets to freeze up.

At the heart of things is the question of whether Greeks can continue to live with the cuts to spending on infrastructure, schooling and health care.

A new government, Syriza, was elected in 2015 and has given voice to those opposed to the austerity package demanded by creditors. Alexis Tsipras, Greek’s Prime Minister, has an aggressive style. He’s also prone to sudden moves. His own negotiating team didn’t know he would announce a referendum on the latest bailout package, scheduled for July 5.

Eurozone leaders have criticized Tsipras for abdicating leadership by putting the bailout package to a national referendum. In their view, he was elected to lead Greece to solutions, not to enrage populist sentiment.

Brinkmanship is not comfortable for either Greece or its creditors. Greece could be the IMF’s biggest bailout ever at US$35 billion dollars for a population of 11 million.

Greece will certainly not pay the funds it owes the IMF on June 30, and has imposed capital controls. The stock exchange and banks are closed. Greeks can only withdraw €60 euros per day.

For now, Greece is in what Nouriel Roubini has aptly called “Grimbo”—a highly uncertain state of affairs with no clear path forward.

The questions hanging over Greece now have been there since Greece joined the EU, and even back to the 1980s when it joined what was then a free-trade zone.

Imagine a province in Canada that had massive debt, no growth and much poorer social services than the rest of the country. Would it be cut loose? Would transfers from the rest of the country continue? Would it vote to exit? And if it did exit, how would this impact the economic health of the rest of the country, and the social fabric of the nation?

That is the situation the Eurozone is facing now. Given our nation’s own existential crises, Canadians can sympathize.

Ailish Campbell is the Vice President – International Policy of the Canadian Council of Chief Executives. The views expressed here are her own.