The party is over. Now the hard work begins on climate change.

Here are the facts on Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions that you should know before environment ministers meet to talk climate change on Friday

Share

The party is definitely over. They all had a great time in Paris with loads of selfies and lots of mutual admiration, but now it’s time for federal and provincial environment ministers to begin the hard work of turning climate change rhetoric into reality. No one should be mistaken about the size of the challenge they face. The wreckage of past climate change plans is all along the road that brought them to tomorrow’s meeting of ministers. They would be foolish to approach their discussions with anything but trepidation.

To help prepare ministers (and those of us watching them work) for their meeting we have gathered some basic facts into a cheat sheet to help get the discussion rolling. If ministers can come away from tomorrow’s meeting with agreement on the facts and common goals, it will have been time well spent. Future meetings can tackle the delicate discussions around who does what, how much will it cost and who pays.

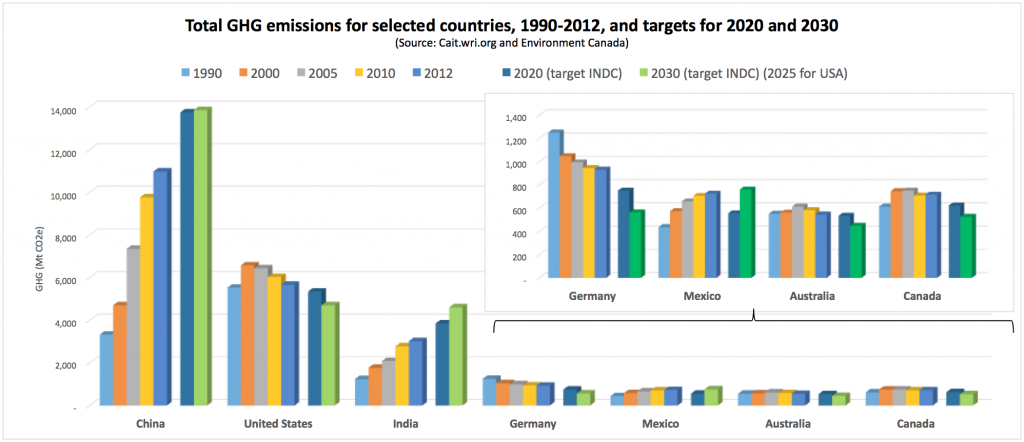

Contributing about 1.6 per cent of global emissions, Canada is among the top 10 global emitters of GHGs. The latest data from Environment Canada puts annual Canadian GHG emissions at about 726 megatonnes (Mt) for 2013. That is slightly more than 100 Mt above our 2020 Copenhagen commitment of 622 Mt and about 200 Mt above our current 2030 commitment of 525 Mt, which is to be considered a “floor” target according to Catherine McKenna, the federal minister of the environment and climate change.

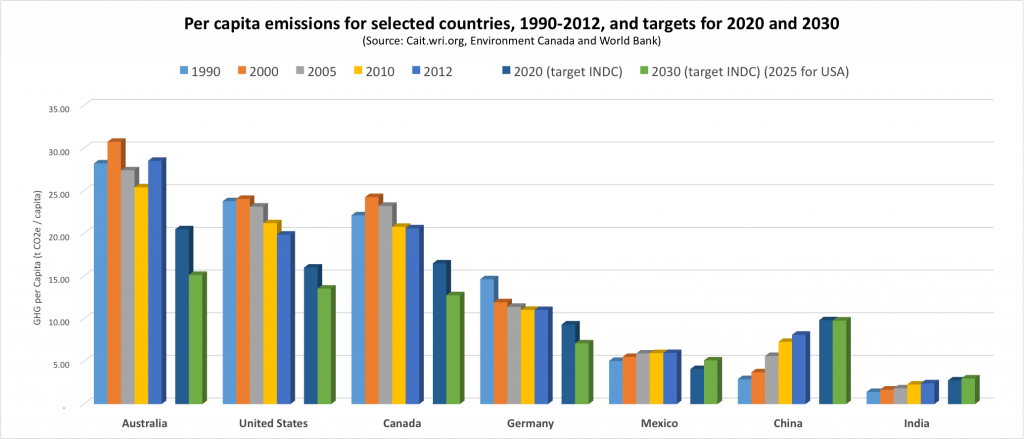

Per capita emissions in Canada stand at about 21 tonnes. Our per capita emissions are comparable to those of the U.S. (20 tonnes) and tower above per capita emissions in China (eight tonnes) and India (2.4 tonnes). Global per capita emissions are now about six tonnes and some estimates suggest that they will need to decline to fewer than two tonnes per capita by 2050 if we are to have a chance of limiting the global mean temperature rise to 2° C.

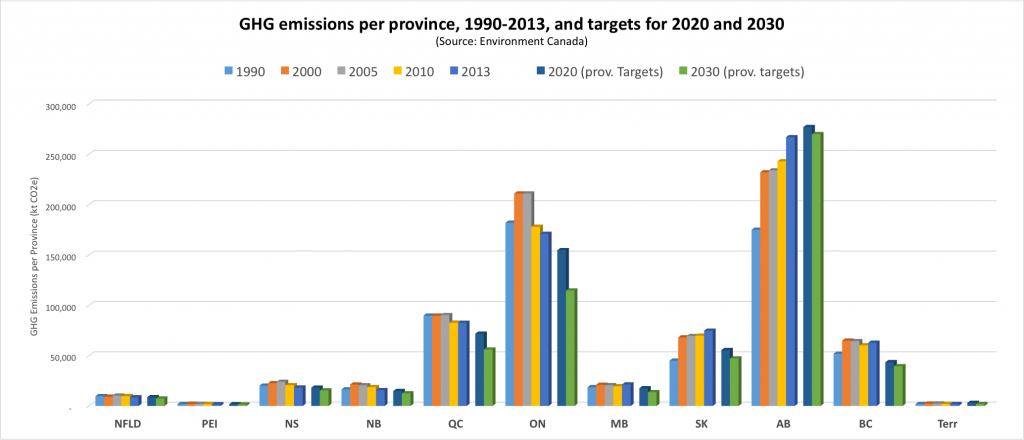

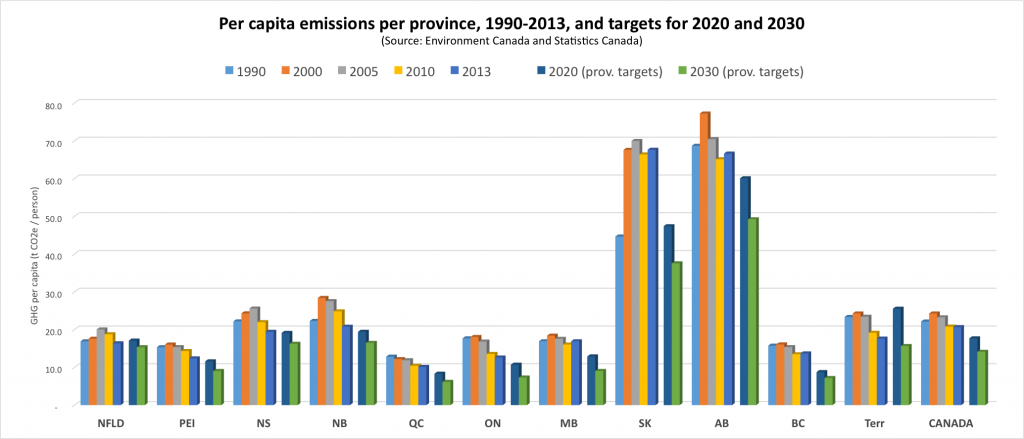

In Canada, most of the concrete action to reduce GHGs to date has come from provinces. Provincial emissions vary widely, ranging in 2013 from 267 Mt in Alberta to 1.8 Mt in P.E.I.

In per capita terms, Saskatchewan and Alberta are among the developed world’s largest emitters at 68 and 67 tonnes respectively. Per capita emissions in B.C., Ontario and Quebec are in the 10-14 tonne range, comparable to the best performers in western Europe.

A number of provinces have announced GHG plans that stretch to 2030. Looking at the three largest provincial emitters, Alberta’s plan has emissions rising from the current level of 267 Mt to peak at about 277 Mt in 2020 before declining to 270 Mt in 2030. In the case of Ontario, the province has pledged to reduce emissions from the current level of 171 Mt to 155 Mt in 2020 and 115 in 2030. Quebec’s plan reduces emissions from 83 Mt currently to 72 Mt in 2020 and 56 Mt in 2030.

It is clear now that the majority of provinces will not meet their 2020 targets. Even if they did, without further actions Canada would fall short of its Copenhagen commitment by about 45 Mt. Assuming that provinces without announced 2030 targets adopt the average stringency of their counterparts with announced plans, and further assuming that all provinces meet their targets, Canada will be about 55 Mt above its Paris commitment for 2030.

These facts define the starting point for tomorrow’s meeting. What they should not do is lessen ministers’ resolve to tackle the issue of GHG emissions. Climate change is happening now. It is already painfully evident in Canada’s North. While we have a big challenge before us, we also have the ingenuity we need to meet it. What’s been missing is the collective willingness of political leaders to take real action. Maybe tomorrow’s meeting will show the commitment to real action that we need.

Paul Boothe is director and Felix-Antoine Boudreault is a fellow at the Lawrence National Centre for Policy and Management at Western University’s Ivey Business School. Both previously worked on climate change issues at Environment Canada.