The perils of being an energy superpower

Canada has energy superpower status, but it isn’t all it’s cracked up to be

Monster Truck in Alberta’s oil sands. Shutterstock.

Share

Back in 2006, then prime minister Stephen Harper marked his debut on the world stage by proclaiming Canada an “emerging energy superpower,” and for the better part of the last two years, commentators and critics delighted in throwing that line back in his face. Just look at what the collapse in oil prices unleashed on Canada’s economy, they’d say. Headlines dismissed Harper’s energy superpower dream as “shattered,” “thwarted” and “dashed.” The ultimate insult seemed to come last week when President Barack Obama finally put an end to the interminable Keystone XL pipeline application process. What superpower can’t even get a pipeline built?

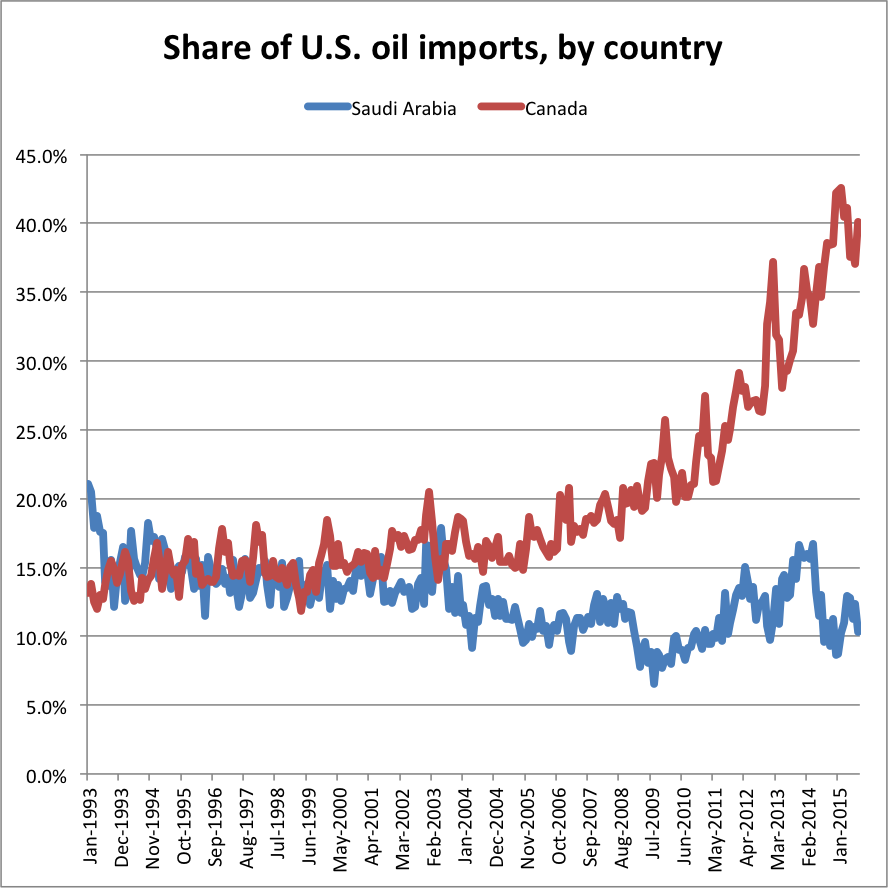

Yet Harper was right. Canada did become an energy superpower, and it remains so today. About that there really isn’t any question. Even without the Keystone XL pipeline, Canada’s share of oil exports to the world’s largest economy have skyrocketed, at the expense of OPEC members like Saudi Arabia.

And Canada’s oil output continues to look truly Herculean in the face of the carnage in the industry brought on by low prices. The latest data from Statistics Canada shows bitumen and synthetic oil production broke record highs in August. Meanwhile a new report from the Paris-based International Energy Agency predicts Canada will be the third-largest source of new oil supply by 2040. If that doesn’t make Canada an energy superpower, I’m not sure what does.

Where Harper and so many others have been mistaken is in the assumption that this superpower status would neatly translate into an extended era of prosperity and clout. We’re still a superpower in a literal sense; it just doesn’t mean as much as it used to.

Here’s a rather unconventional way to think about the economic law of supply and demand that’s upending Canada’s energy superpower narrative. If you’ve haven’t seen the 2004 superhero cartoon The Incredibles, the movie’s villainous mad inventor, Syndrome, had a thoroughly ingenious scheme to finish off his nemesis, Mr. Incredible, once and for all. His plan: to eventually sell all his powerful inventions to the public so that one day “everyone can be superheroes, everyone can be super. And when everyone’s super (bwa-ha-ha!) no one will be.”

That, in a nutshell, is what’s happened in the world of global energy. When Harper coined his catchphrase, Canada’s oil sands stood out as an anomaly in a world of dwindling energy supplies. Talk of peak oil, the concept that the world had reached its maximum level of petroleum production, was at a fever pitch. Then the world started to hear about this other region in the U.S. called the Bakken, and soon, thanks to technological advances, America’s oil production exploded past Canada’s. Now Mexico is emerging as an energy superpower. So is Iran, after being locked away in a box of its own making. So too is Iraq. When everyone is an energy superpower, no one is an energy superpower.

Canada’s energy troubles, however, go beyond the global oil glut that now looks as if it may drag on for several more years. Low oil prices would have been far more manageable had costs not skyrocketed to the extent they did in the Alberta oil patch. Unfettered development of new projects put incredible strain on the supply of labour and machinery. This has put Canada at a particular disadvantage compared to countries with lower production costs, giving us far less control of our own destiny than being a energy superpower might be thought to entail.

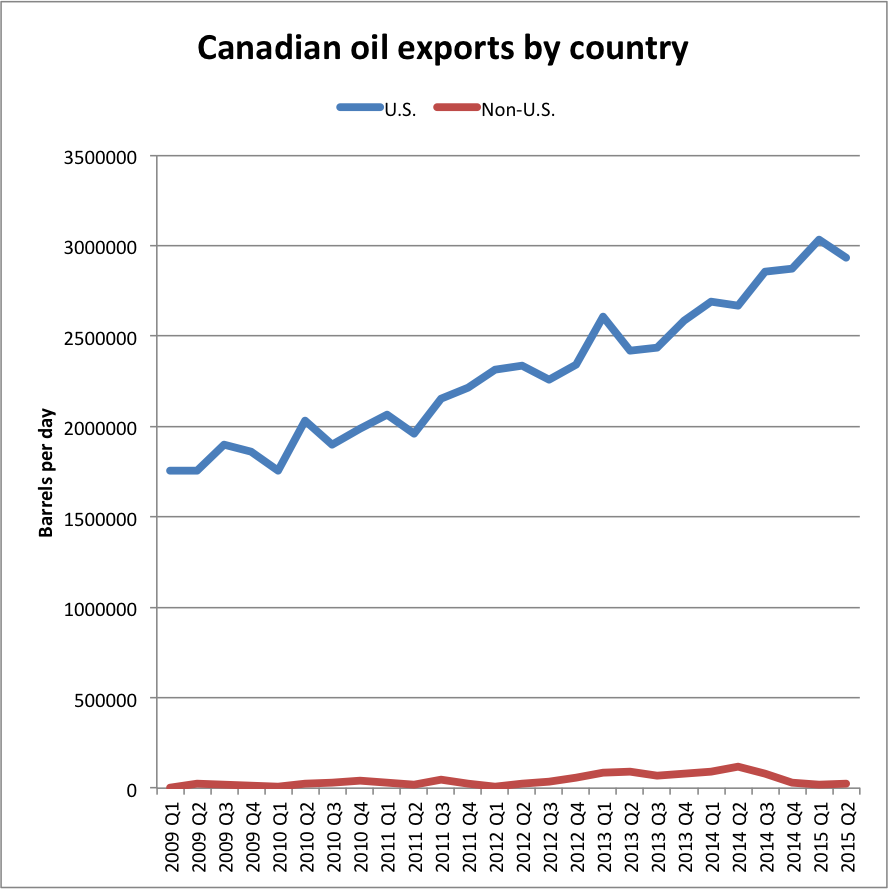

We’re still stuck with our greatest energy handicap: our lack of adequate energy infrastructure to get Canadian crude to more markets. The death of Keystone XL drove home that point, reminding us once again of exactly how trapped Canada’s energy wealth is. As of the second quarter, 99.1 per cent of all Canadian oil exports went south of the border, through existing pipelines and by rail. That dependence on the U.S. has only intensified. Since 2009, according to Canada’s National Energy Board, oil exports to the U.S. soared 70 per cent, while Canadian oil exports to the entire rest of the world inched up just seven per cent.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau was a supporter of Keystone XL but has yet to fully endorse either of the next two most viable routes—the Trans Mountain pipeline to Vancouver or the Energy East pipeline to New Brunswick. As the new era of low oil prices drags on, getting at least one of those built will become even more vital. Only then might we enjoy at least some of the benefits that should come with being an energy superpower.