The Quebec budget starts the structural reform the province needs

From fixing the ‘bad habit’ of special tax credits to removing roadblocks to growth, the Quebec budget gets a lot of things right

Share

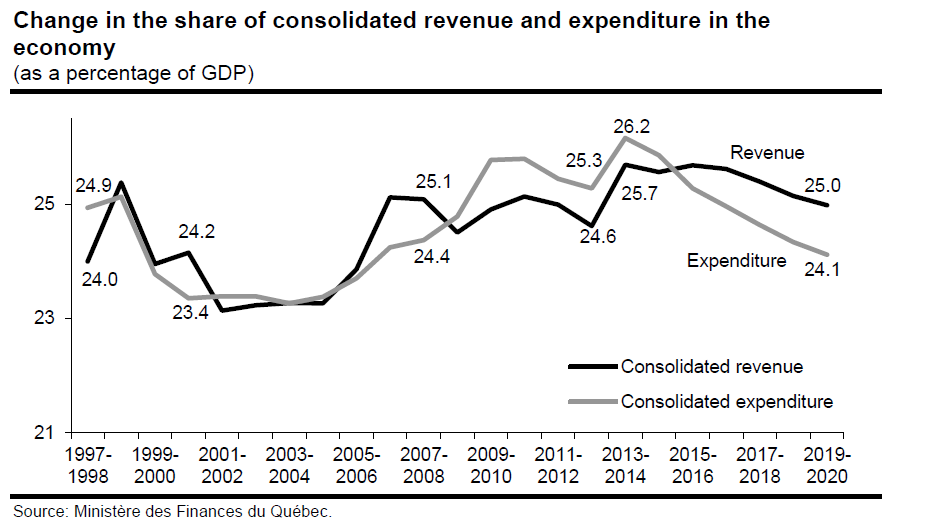

The Quebec budget, the second from the government of Philippe Couillard, continues on the path set out in the first one: the rate of growth of public spending has been cut back yet again, and the goal is to bring the expenditure-to-GDP ratio back to where it was before the recession hit. But the main thrust of the budget was on structural reform and expectations in the lockup were guided by the recommendations published by the report released last week by the Quebec taxation review committee, chaired by the Université de Sherbrooke’s Luc Godbout. Although there was no mention of an increase in the Quebec Sales Tax (the budget plan says that the idea is “under study”), several measures in the report were incorporated into the budget.

Some quick reactions:

A surprisingly positive outlook: Quebec imports oil, so lower oil prices are an unambiguously positive development for the Quebec economy. (Concerns that lower oil prices will affect equalization payments are for later on; the formula for calculating equalization payments is based on lagged data so that provinces can make plans a couple of years out.) Stronger economic growth—and hence revenue growth—no doubt explains why the QST was not increased, even as some taxes were cut.

Corporate tax cuts: The general Quebec corporate income tax rate will be gradually reduced from 11.9 per cent to 11.5 per cent over the next five years. Reducing corporate taxes was a recommendation of the Godbout Report and its implementation is not a surprise: the change both is small and gradual. What is more intriguing is its treatment of small businesses. Recent research has generated much criticism of the tax reductions offered to small businesses. To the extent that many small business owners are content to remain small, a lower tax rate is not much of an incentive to grow: the reward is an even higher general corporate rate. And many small businesses are simply instruments for tax planning on the part of high earners.

The Godbout Report recommends eliminating the small business deduction for very small firms, and the government has accepted this recommendation. The deduction will now only be available for firms with more than three employees. The Quebec budget documents note that of the 75,000 companies that will be affected, some 42,000 don’t have any employees.

The ‘Tax Shield’:

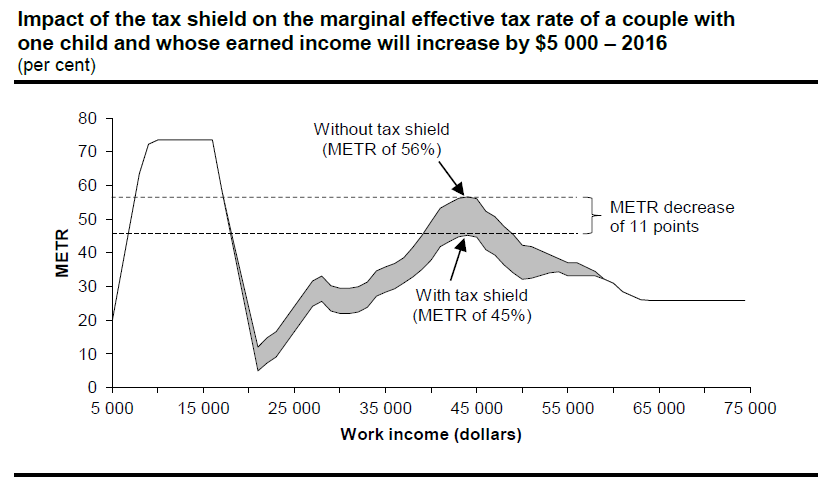

A side-effect of means-tested, cash-transfer programs is that they are reduced as incomes increase. This clawback effectively acts as a tax as far as disposable income goes, and can be an important work disincentive. This is an undesirable effect for any economy, and especially so for an economy in which the working-age population is shrinking. The “tax shield” attenuates this effect somewhat by reducing the rate at which benefits are withdrawn as family incomes increase.

Periodic review of tax expenditures: This is another recommendation taken from the Godbout Report, and a welcome one. Governments at all levels have developed the bad habit of implementing special tax treatments and tax credits and then forgetting about them. If Quebec follows through on this problem, it could set a good example for other governments.