This slowdown in Canada’s economy suits the Bank of Canada just fine

Econo-metrics: Any hotter and the Bank might have to hike interest rates again, walloping Canadians who are carrying a massive amount of debt

Production Associates work on dashboard assembly at Honda manufacturing plant in Alliston, Ontario March 30, 2015. REUTERS/Fred Thornhill

Share

Canada’s economy has come back to earth.

Statistics Canada reported Dec. 1 that gross domestic product grew at annual rate of 1.7 per cent in the third quarter, only a tick slower than the Bank of Canada’s October prediction of 1.8 per cent.

You should feel comfortable with that. Canada’s economy had been tiger-like, begging to be tamed by higher interest rates. Now, growth is in the range of what the central bank thinks can be sustained without stoking too much inflation. We do appear to have entered a Goldilocks phase.

There are a few people who are going to be extremely happy with the latest batch of data. They are Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne, and Quebec Premier Philippe Couillard.

StatsCan also released new employment data, and they were unambiguously positive for the three politicians I just mentioned. The national unemployment rate dropped to 5.9 per cent in November, the lowest since early 2008. Ontario’s jobless rate (5.5 per cent) was the lowest since 2000, and Quebec’s (5.4 per cent) was the lowest on record. Those are the kinds of numbers that allow prime ministers and premiers to say their plans are working.

To be sure, there is doubt about whether jobs still win votes, if they ever did. A Nanos Research poll for Bloomberg News found that only about a quarter of Canadians rated Trudeau as a good manager of the economy, even as annualized GDP growth exceeded four per cent for the first time in almost two decades. Wynne’s approval ratings are terrible, and the lead of Couillard’s Liberal Party in polls is remarkably narrow, given Quebec’s rise to economic stardom on his watch.

So it may no longer be as simple as the economy, stupid. Gillian Tett of the Financial Times just wrote about new research that suggests Americans’ perception of the economy is guided more by partisanship than facts. Andrew Coyne of the National Post thinks Canadian voters might be the same. Still, even if that’s true, no governing politician would exchange a strong economy for a weak one. Trudeau, Wynne, and Couillard all have been attacked over their economic policies; in the case of Trudeau and Wynne, for choosing to run budget deficits, and in the case of Couillard, for doing too much to narrow them. Their opponents will struggle to make those critiques stick with unemployment at or near the lowest levels on record.

READ: Quebec’s unemployment rate is lower than any time since the 1976 Olympics

This brings us to a fourth person who will be especially interested in these numbers: Bank of Canada Governor Stephen Poloz.

Poloz may have to wait until after he retires, but at some point he will be recognized for having a pretty good read on the rhythms of the Canadian economy. We probably avoided a recession in 2015 because the central bank cut interest rates before most economists realized how much damage the collapse of oil prices was going to cause. This year, Poloz’s central bank surprised analysts with consecutive interest-rate increases over the summer. Then in October, the Bank of Canada went back on hold, arguing that further increases were unnecessary at that time because growth would slow. Poloz was right again.

The Bank of Canada’s last scheduled interest-rate decision this year is Dec. 6. The message from policy makers in October was that they definitely would be raising rates in the future, but that they were uncertain about how quickly they would do so. Incoming data, they said, would guide them.

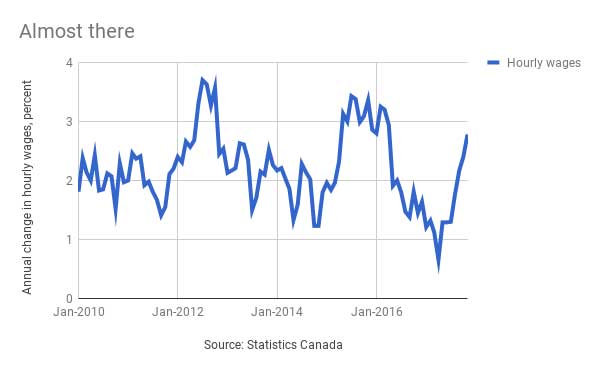

All things equal, the central bank would be getting ready to raise interest rates next week. At the end of September, Poloz elaborated on the variables that would have the greatest influence on future decisions. One was the extent to which Canadians can manage their record pile of debt. That mostly will be determined by the level of employment, which is about as good as it ever gets, according to StatsCan’s November survey of the labour market. The latest figures also track wages, another of Poloz’s key variables. Despite years of ultra-low interest rates, salaries barely have kept pace with inflation. But that could be changing. The average hourly wage was 2.8 per cent higher in November than a year earlier, the biggest increase since April 2016. The GDP report showed compensation of employees increased 1.3 per cent in nominal terms, the biggest gain in 11 quarters, according to StatsCan.

Fatter paychequs imply greater spending power, which would put upward pressure on inflation. But Poloz and his inner circle of advisers on the governing council will probably opt against ending 2017 with an interest-rate increase. Until the last few months, wages had been stagnant for more than a year. That means there is room to run.

The central bank will also be concerned about lacklustre business investment and a big drop in exports in the third quarter. Another one of the factors Poloz highlighted in September was “capacity,” which is the term economists use to describe the extent to which companies are equipped to handle their order books. When demand is strong, businesses tend to expand to take advantage of the opportunity to increase profits. If they don’t, prices will rise because there is too little supply. Poloz has made clear he is holding out for the former, which is why he is inclined to raise interest rates only gradually.

Business investment in nonresidential structures and machinery and equipment surged to an annual growth rate of 10.6 per cent in the first quarter, then slowed to 8.2 per cent over the following three months. In the third quarter, growth dropped to 3.2 per cent. Worries over whether the North American Free Trade Agreement will survive Donald Trump could explain some of the decline. Also, Canadian investment is tied to exports, which plunged 10 per cent in the third quarter, when measured by annual rates. The drop reflects temporary shutdowns at automobile factories, but also suggests the dollar’s appreciation over the summer hurt exporters. That’s an argument for the Bank of Canada to leave interest rates unchanged, since an increase would boost demand for interest-bearing assets, putting upward pressure on the currency.

The final argument against an interest-rate increase this month relates to the central bank’s concerns about household debt. Poloz knows his interest-rate policy is a driving force behind the credit boom. But now that households are so heavily burdened, the central bank also knows it risks triggering a recession if it raises borrowing costs too quickly.

Household consumption grew faster than disposable income in the third quarter, as revenue from dividends declined and interest paid on consumer credit increased 5.9 per cent. That’s an unhealthy dynamic, and illustrative of the balancing act that faces the central bank over the next couple of years as it attempts to return interest rates to a more normal setting.

Domestic consumption remains the Canadian economy’s main engine. Poloz won’t risk choking it until it’s clear investment and exports are ready to take over. There isn’t much evidence yet that they are.

MORE ABOUT ECONOMY:

- Canada must step up to defend a globalized world

- If NAFTA dies ‘all hell will break loose’

- What is the recipe for a successful nation?

- Bill Morneau’s shift from long-term strategy to immediate benefits

- America is making country of origin rules a NAFTA priority. Look out, Canada.

- Dominic Barton wants Justin Trudeau to think big about the economy. Will he?

- Canada’s economy surges in second quarter

- An interview with Justin Trudeau