What Canada’s trade strategy should look like under Trump

Canada should continue to position itself to set the global standard for openness to the movement of products, expertise, people, technologies, and ideas

The Ambassador US/Canada bridge and border crossing at Windsor, Ont. and Detroit, MI on July 11, 2014. (Stephen C. Host/CP)

Share

With the election of Donald Trump as U.S. president, Canada’s privileged access to the world’s largest market is at risk. Canada needs a proactive U.S. strategy—and a global one—to minimize the threat and perhaps even turn it into an economic opportunity.

With the election of Donald Trump as U.S. president, Canada’s privileged access to the world’s largest market is at risk. Canada needs a proactive U.S. strategy—and a global one—to minimize the threat and perhaps even turn it into an economic opportunity.

During his presidential campaign Trump pledged to renegotiate or withdraw from the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and to exclude foreign suppliers from new infrastructure spending, among many other anti-trade measures. With 70 per cent of Canadian exports destined for the United States, U.S. protectionism is especially problematic for Canada. These types of measures could hurt Canada’s sales to its most important export market badly and hit overall economic growth hard. If president Trump imposes tariffs on goods from China and Mexico, this could turn into an all-out trade war, threatening regional and global economic stability, in which Canada also has a strong stake.

Canada’s strategy for dealing with the Trump administration on trade could have three planks to start.

First, Canada should develop some practical proposals in areas of potential alignment. Policy-makers should use the time between now and the presidential inauguration on Jan. 20 to go through recent congressional bills and U.S. departmental reports on energy security, infrastructure, innovation, security, and regulation. They should identify discrete initiatives that align with Canadian interests in these areas. From there, Canada should develop proposals of what the two countries can do together, as deal-making seems to be a likely feature of a Trump presidency.

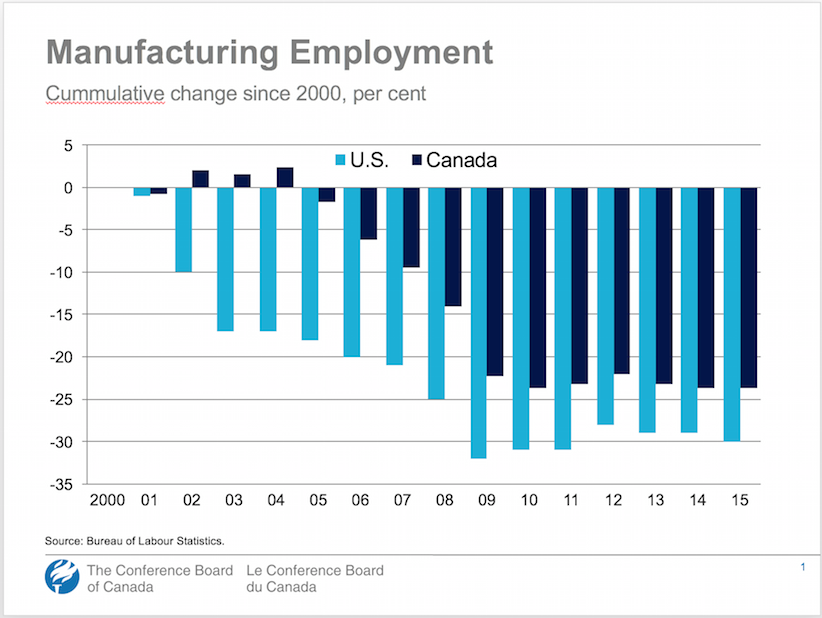

Second, president-elect Trump’s post-election rhetoric has focused more on maintaining American jobs than the specifics of NAFTA. So Canada’s strategy needs to address U.S. jobs. Canada is not taking manufacturing jobs from Americans—our manufacturing job losses have been similar to those in the U.S.

(Automation and offshoring of low-skilled labour intensive manufacturing to Asia are the likely culprits in manufacturing job losses across North America.) Further, NAFTA partners essentially make things together in an integrated supply chain. This means that Canadian exports have a high share of U.S. content, so imposing barriers on Canadian exports would essentially penalize U.S. exports and lead to U.S. job loss. A Canadian strategy needs to emphasize these realities, ideally by getting the many American companies with business interests at stake to deliver the message to their representatives.

Third, should Trump decide to go through with a NAFTA renegotiation, Canada should have a wish list in mind. For all of its benefits to all three member countries, NAFTA (which is 22 years old) is out of line with the realities of how businesses operate today. Modernizing the agreement could advance Canada’s interests in terms of trade in services, data, ideas and expertise—all areas that would support U.S. jobs and innovation.

Beyond the U.S., Canada now has a major window to pursue its positive interests in global markets. As the U.S. and Europe turn inward, The Economist magazine and others are recognizing Canada as the poster child for openness. Canada should continue to position itself to set the global standard for openness to the movement of products, expertise, people, technologies, and ideas. Being the standard bearer of openness could in turn help to advance Canada’s interests in global growth and stability to counter the threat of U.S. isolationism.

As countries recalibrate their strategies, Canada should have its doors open to advance trade agreements, business interests, and attract investment. Canada should continue to explore opportunities with China, Japan, and other Asian markets such as ASEAN. The scale and growth potential of opportunities on offer in China and other emerging markets is massive.

Overall, Canada has benefited tremendously from openness to trade and investment, boosting this small country’s living standards far higher than they would otherwise have been. But not all have shared in the benefits, and some workers are left behind in the short-term. This phenomenon in Europe and the U.S. has at least partly driven the backlash against openness. A key part of Canada’s positive trade strategy should ensure that the needs of Canadian workers that have been left behind are being dealt with through education and economic development policies.

This proactive policy approach would be a solid start for Canada to minimize this threat to Canada’s—and the world’s—economic interests and stability.

Danielle Goldfarb is director of the Global Commerce Centre at the Conference Board of Canada