What slow inflation could mean for interest rates

Econ-o-metrics: The Bank of Canada’s critics will say stubbornly low inflation means the latest rate hike was a mistake. But it might just mean the bank waits longer until the next hike.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Michelle Siu

Share

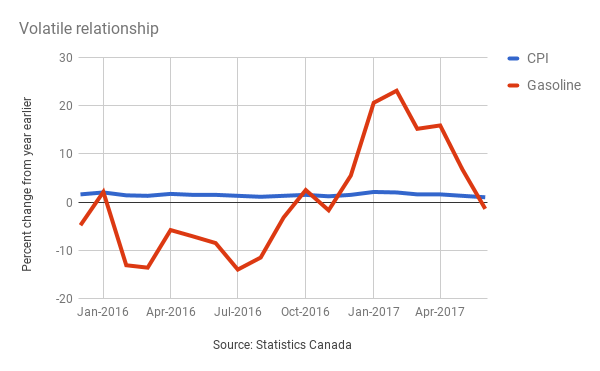

Statistics Canada’s Consumer Price Index rose one per cent in June from a year earlier, as cheaper gasoline allowed Canadians to stretch their paycheques, the agency reported July 21. Alternative measures of inflation that adjust for the more volatile components of the price basket, such as gasoline, were moderately higher than the headline number.

Why it matters:

When the Bank of Canada raised interest rates on July 12, Governor Stephen Poloz said the timing of the next increase will depend on future data. True, the central bank indicated that it would be looking past inflation figures, arguing that the numbers are being skewed currently by idiosyncratic factors. Fine. But the central bank will still be watching prices closely to check that its assumptions are correct. Policy is tied to inflation, so it has no choice.

READ MORE: Why the Bank of Canada hiked interest rates

The trend:

Inflation has been slowing all year, and the June reading matches recent lows from the autumn of 2015. The last time prices were increasing at a slower rate than one per cent was May 2015, when the headline CPI increased only 0.9 per cent.

The modified measures of inflation that policy makers watch to get a clearer sense of the trend are stronger. StatsCan’s core index, which subtracts food and energy prices, was 1.4 per cent, the same as in May. The average of the Bank of Canada’s three preferred inflation measures was 1.4 per cent, slightly faster than the 1.3 per cent average of the previous month.

Glass half full:

Weak inflation means we have more money to spend—and yes, we’re spending it. Separately, StatsCan reported that retail sales rose 0.6 per cent in May, the third consecutive monthly increase and the latest indicator that Canada’s economy is on a roll. It’s a mystery why that strength isn’t putting more upward pressure on prices. The Bank of Canada thinks inflation is being influenced by weaker energy costs and an odd slowing in the upward trajectory of automobile prices. (Prices of passenger vehicles dropped 0.2 per cent in June, the first decline since February 2015.) Neither of those things should last.

Still, the central bank concedes that changes in the retail industry could have altered inflation dynamics. Consider the spread of e-commerce, which increases competition, but also allows retailers to reach more customers at a lower cost. StatsCan is so new to tracking digital sales that it can’t adjust for seasonality. It’s unadjusted data shows Canadian retail e-commerce increased almost 47 per cent in May from a year earlier. That represents only 2.3 per cent of total retail trade, but growth like that suggests something meaningful is happening in the way goods are bought and sold.

Glass half empty:

In isolation, the inflation data imply that the Bank of Canada made a mistake by raising interest rates. The central bank aims to keep the CPI at the midpoint of a comfort zone that stretches from one per cent to three per cent. Typically, inflation of one per cent signals economic weakness because there is too little demand to force prices higher. The central bank made clear that it thinks current readings of inflation are sending false signals. There will be questions about that judgment until the CPI moves higher.

Bottom line:

The Bank of Canada’s only official mandate is to keep the CPI at two per cent, and it has assured us that inflation is coming. Stronger retail sales bolster that case, although StatsCan noted that if not for automobile sales, retail trade would have been little changed in May. Ultimately, with inflation weak, the Bank of Canada will feel little pressure to raise interest rates quickly. The trip back to a more typical interest-rate setting could be a slow one.