Why building a massive oil sands refinery would be a bad idea

There are far more important things for Alberta’s government to spend its money on than subsidizing an oil sands refinery

Share

On Oct. 6, the Alberta Federation of Labour (AFL) released a new report that purports to show that refining in Alberta is a viable business opportunity—more than viable, in fact—with internal rates of return projected at between 16 and 25 per cent for a new, greenfield refinery mega-complex. If you could promise rates of return like that, anyone would build a refinery, but are rates of return like that possible in today’s Alberta? Perhaps, but they are only going to be earned if the value in our natural resources has been destroyed in advance. That’s hardly value-added.

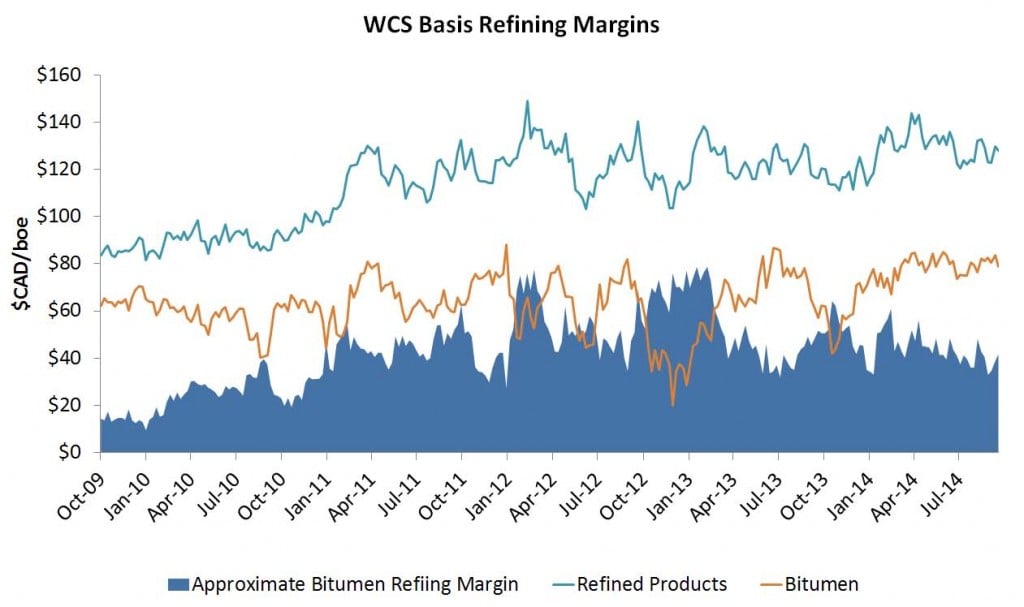

The push for more refining in Alberta has gained momentum in the past few years, as the so-called “bitumen bubble”—an Alberta manifestation of discounts for crude in much of North America—saw the gap between Alberta bitumen and refined products grow to historic levels. This occurred because the refined products market largely tracked higher global crude prices. As the image below shows, the value of a barrel of bitumen has, at times, been over $60 per barrel lower than the value of the refined products that could be produced from it. Over the past five years, the value of refined products on global markets has averaged about $45 per barrel more than the value of bitumen in Alberta—a margin large enough, were it to be maintained, to put any refinery solidly in the black.

Figure 1 Implied bitumen value based on Western Canada Select and Edmonton Condensate prices. Refined products value based on Los Angeles Harbour prices, weighted for standard yield from a bitumen refinery, net of typical pipeline transportation costs. Each barrel of bitumen produces a composite barrel of 0.38 barrels of CBOB and 0.25 barrels of CBOB, both gasoline blending components, as well as 0.33 barrels of low-sulfur diesel, with the residual in petroleum coke, which is valued at zero. Source: Bloomberg

The AFL analysis was developed by U.K.-based economist and former Mobil executive Ed Osterwald. (Ironically, the AFL was apparently unable to find a Canadian firm willing to do the work, and one assumes Osterwald was here on some form of temporary work visa.) The results are based on a project cash flow model of a refinery capable of processing 308,000 barrels per day of bitumen. That’s a big project by any measure—it would be the largest refinery in Canada and among the 10 largest in North America.

Osterwald’s report maintains that this refinery could be built in Alberta for about $10 billion—this despite the fact that a similar refinery project, at less than 20 per cent of the size, is projected to cost over $8 billion, and those costs may well increase before that project is done. When questioned on this assumption, Osterwald maintained that his figure was attainable if the builder chose the right partners, and had appropriate government support—what either of those meant wasn’t really clear. That was, unfortunately, the story of the day as interested readers were left with no clear answers as to what assumptions underpinned the analysis, and the report offers little in the way of clues.

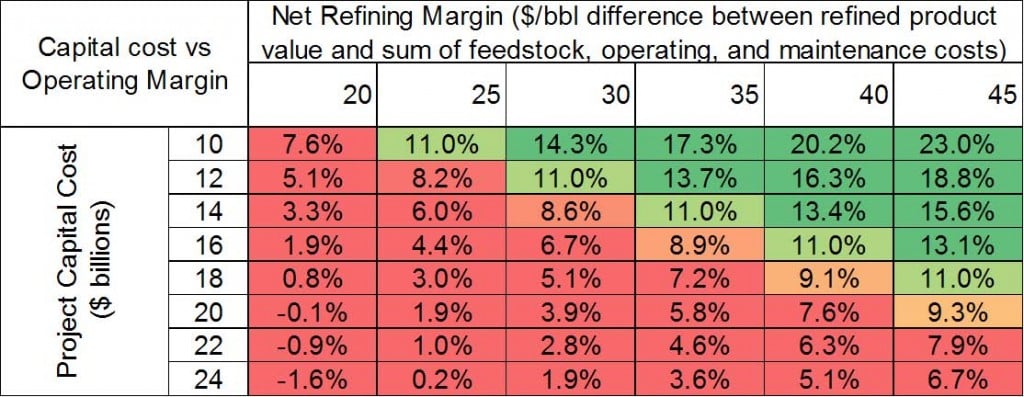

Figure 2 Refinery after tax internal rates of return, given capital cost and net refining margins. Source: Author’s calculations.

Could a new refinery in Alberta earn a 16-25 per cent rate of return? Sure, it could. Refineries are big bets on small spreads—you spend a lot of money up front to capture the difference between the value of your inputs (in this case bitumen) and the value of your outputs, net your refining and maintenance costs. If you spend $10 billion on a 300,000-barrel-per-day refinery, and it operates for 50 years, you’d need an average, net refining margin of between $33 and $50 per barrel to earn that kind of return. This is not unreasonable given recent history—the average price gap has been over $45 per barrel between bitumen and refined products, and refining operating and maintenance costs are generally below $10 per barrel. If price gaps like the last five years are maintained, a refinery on this scale might still be viable if it cost a more reasonable $18 billion to $20 billion to build.

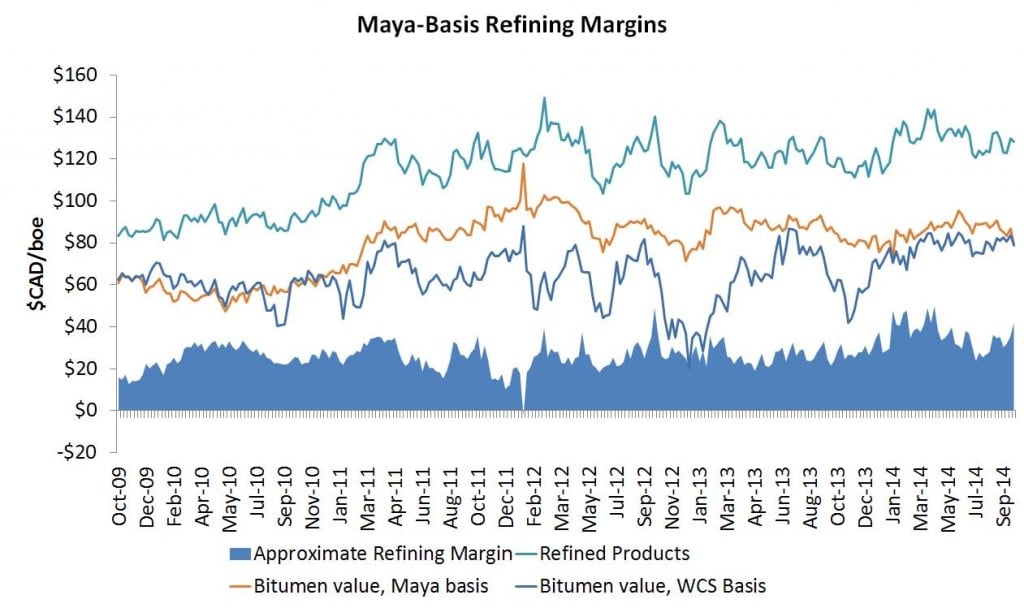

But will these price gaps be maintained, and what does it mean if they are? The margins any refinery in Alberta will earn depend on pipelines and pace of development—if Alberta is connected to global markets and/or if production is managed to match pipeline capacity, diluted bitumen in Alberta will trade at a value similar to Maya crude traded in the U.S. Gulf Coast, net transportation costs. It will not capture a world light oil price, of course, but its price will come to reflect its value to refiners globally. To give you a sense of how much that matters, Figure 3 below makes all the same calculations for refining margins, but assumes that pricing relationship—diluted bitumen valued in Edmonton at Maya prices, net a $6.50 per barrel pipeline toll.

Figure 3 Implied bitumen value based on Maya and Mont Belvieu Natural Gasoline prices. Refined products value based on Los Angeles Harbour prices, weighted for standard yield from a bitumen refinery, net of typical pipeline transportation costs. Each barrel of bitumen produces a composite barrel of 0.38 barrels of CBOB and 0.25 barrels of CBOB, both gasoline blending components, as well as 0.33 barrels of low-sulfur diesel, with the residual in petroleum coke, which is valued at zero. Source: Bloomberg.

This changes the game significantly—using Maya prices to value diluted bitumen, adjusted for transportation, the average refining margin reduces to about $33 per barrel which, once operating and maintenance costs are taken into account, would likely be reduced to about $23 per barrel—right around the break-even margins you’d need to pay off a $10-billion refinery, but nowhere near enough to cover a $20 billion one. Realized refinery margins are typically this small or smaller—in the first quarter of 2014, Valero reported net revenues for its Gulf Coast operations, before taxes, of $6.19 per barrel refined—and so no one is going to jump into a refinery in Alberta unless they can expect discounted bitumen in the long term.

There’s no question that refineries can be viable in Alberta, if conditions lead to a large enough discount on bitumen. The AFL would have you believe that creating incentives for refining here is acting like an owner—capturing the value from the bitumen and creating jobs, even if that comes via a bitumen discount. It’s not. Through discounted bitumen, we would be transferring value from all Albertans and some extraction companies to some Albertans and refinery companies. In terms of jobs, there aren’t many unemployed oil workers hanging out in Alberta, and so extraction and refining industries would compete for many of the same workers, and offer similar job security—you’re not creating jobs, you’re transferring them from one part of the supply chain to another. From a fiscal perspective, profits earned via bitumen extraction are subject to resource royalties which can be as high as 40 per cent over and above corporate taxes while profits earned by refineries are subject only to corporate taxes. From a value-added perspective, an oil sands extraction plant adds far more value to buried oil sands ore than a refinery adds to bitumen. Discounting bitumen to force a substitution between extraction and refining isn’t acting like an owner as all Albertans should demand our government do—it’s acting like a politician. We should direct our politicians not to spend bitumen in ways they would not be prepared to spend money.

The question Albertans should ask is: if we’re going to spend billions of dollars of government money or billions of dollars worth of bitumen, would we like to spend it offering a better rate of return to refineries or on other things we value like health care, education, and infrastructure—areas that incidentally tend to be more labour- and union-intensive than refining? Count me in for the second choice. Refining is not an opportunity for value-added in Alberta, it’s what will happen if we allow value to continue to be destroyed by selling our resources at a discount. That’s not something that should be celebrated as an opportunity—it’s exactly the opposite.