Why child benefits matter—and why they need reform

Today’s child benefits system is too cumbersome for anyone to understand

(Shutterstock)

Share

The federal government targets substantial dollars at families with children. Many Canadians likely remember the old Family Allowance in place from 1945 to 1992 that paid out $35 each month per kid. Over the last twenty years, though, much has changed. Here are three things you should know to get up to speed on the current state of government transfers to families with children.

1. Family benefits are big

For budget year 2014-15, the federal government will spend $13.2 billion on the three main federal benefits—the Canada Child Tax Benefit (CCTB) the National Child Benefit Supplement (NCBS), and the Universal Child Care Benefit (UCCB). Most of these dollars are focused on lower and middle income Canadians, as the CCTB and NCBS are reduced when families hit higher income levels.

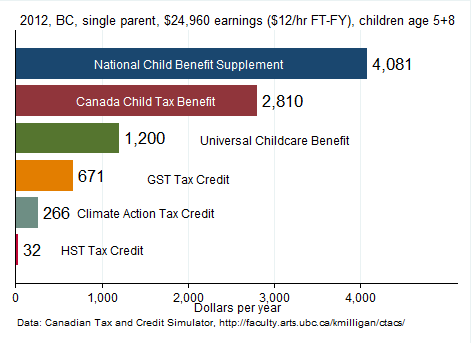

What does this mean for a real-life Canadian family? Imagine a single parent with two kids in British Columbia working a full-time lower-paying job. At $12 an hour, total earnings amount to about $25,000 per year. At this earnings level for 2012, the parent would be eligible for cash transfers of $9,060 a year, as laid out below. The federal benefits mentioned earlier are joined by provincial cash benefits like the Climate Action Tax Credit and the HST Tax Credit. The end result is $755 per month—a large income boost compared to the $2,080 per month coming in from the job.

2. Family benefits change lives

Family benefits have a substantial impact on the finances—and the lives—of Canadian children and families.

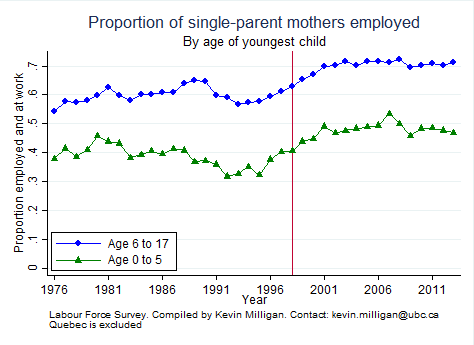

In the labour market, well-designed incentives give a boost to those who are working. Evidence from Canada and around the world indicates strongly that labour force attachment is significantly enhanced by well-designed child benefits. This can be seen (in rough analysis that holds up when subjected to more advanced scrutiny) by simply looking at the growth in the proportion of single mothers working after benefits were expanded in 1998.

Beyond work decisions, the resources received by families can make a big difference to the lives of children. Evidence from child benefit expansions in Canada, food stamps in the U.S., and other programs lends support to the idea that alleviating poverty brings tangible improvements for child outcomes by improving health, family stress, and educational outcomes.

3. Canada’s system is too complicated

Beyond the cash benefits listed in the BC example above, other Canadian families can be eligible for tax benefits like a non-refundable credit on the tax form, the Working Income Tax Benefit, and provincial supplements like the BC Family Bonus or the Ontario Trillium Benefit. Taken together, I can count up to ten different benefits for which a BC family could be eligible. That doesn’t even include the tax benefits for spending on fitness, arts, or childcare.

If you dig deep into a spreadsheet you can figure out that several of these child benefits duplicate or even work against each other. For example, why do we have a UCCB that discourages mothers from working at the same time as the WITB and NCB encourage mothers to work?

A bigger problem is that you have to dig deep into a spreadsheet to figure all that out. The system is too cumbersome for anyone to understand what is going on. This complexity reduces transparency and likely lowers how much families respond to the incentives buried deep within.

I’ve written elsewhere about how we might approach a reform to child benefits. I don’t know for sure if my skeleton proposal gets things entirely right, but I do know that reform is needed and would be worthwhile for Canadian families.