Why free trade is a losing issue for Hillary Clinton

Trump’s angry rhetoric against free trade appeals to communities hit hardest by lost manufacturing jobs, leaving little room for Clinton’s fuzzy stance. That’s bad for the whole world.

Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton speaks to members of the media before boarding her campaign plane at Westchester County Airport. (Andrew Harnik/AP)

Share

Amidst all the highlights from Monday night’s presidential debate that have been pored over and dissected—Trump’s sniffles, his squirming over the birther issue, his dodge of questions about his tax return, his rambling incoherence on the matter of his temperament, etc.—one moment has not received nearly the same attention. Which is remarkable, because it poses a real threat to Hillary Clinton on election day. And that’s her fuzzy stance on trade.

The exchange between Clinton and Trump about trade came relatively early in the debate, and was the self-proclaimed billionaire’s most coherent moment of the night. For an anti-politician who’s proven himself mostly incapable of maintaining a train of thought longer than a single tweet, his assault on Clinton was direct, succinct and targeted at a very specific slice of the American electorate.

Trump: “You go to New England, you go to Ohio, Pennsylvania, you go anywhere you want, Secretary Clinton, and you will see devastation where manufacture is down 30, 40, sometimes 50 per cent. NAFTA is the worst trade deal maybe ever signed anywhere, but certainly ever signed in this country. And now, you want to approve Trans-Pacific Partnership. You were totally in favour of it. Then you heard what I was saying, how bad it is, and you said, ‘I can’t win that debate,’ but you know that if you did win, you would approve that, and that will be almost as bad as NAFTA. Nothing will ever top NAFTA.”

Clinton: “Well, that—that is just not accurate. I was against it once it was finally negotiated and the terms were laid out. I wrote about that in—

Trump: You called it the gold standard.

Clinton: — I wrote about — well, I —

Trump: You called it the gold standard of trade deals.

As is often the case, the exchange contained embellishment by the Republican candidate. It wasn’t Trump who convinced Clinton to abandon her support for the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), to which Canada and 11 other nations are signatories. After initially promoting the TPP agreement as President Obama’s secretary of state, Clinton the presidential candidate then said she would reserve judgment until the agreement was finalized, before ultimately coming out against it last October. Her change of heart, better described as a flip flop, came in response to the surge in popularity of the Democratic party’s protectionist wing, led by Bernie Sanders and his isolationist platform.

Yet Clinton is only a convert to protectionism to a certain, malleable degree. In the debate she defended her husband’s economic record as Trump attacked former president Bill Clinton for signing the NAFTA trade deal between the U.S., Canada and Mexico. She acknowledged that as a senator she had voted in favour of some trade deals, and opposed others. Then, perhaps to affirm her tough-on-trade bona fides, she repeated her pledge, made this past summer while at a stop in Cincinnati, to appoint a special trade prosecutor to ensure countries (Read: China) abide by existing trade deals.

Clinton is attempting to walk a line on trade that satisfies both the protectionists and the proponents of globalization that exist within the Democratic Party. Trump, on the other hand, has dispatched any pretence that the Republicans are still the party of free trade, and has promised to tear up NAFTA, cancel the TPP, and wage trade wars against any nation that crosses America.

Many Americans love him for it. Trump’s message resonates especially loud in Midwestern rust belt cities that have been gutted by factory closures over the last quarter-century. Since 1990 the Cleveland area alone has shed nearly half as many manufacturing jobs as the entire province of Ontario. It’s a similar story across the rest of Ohio and Pennsylvania, crucial swing states that are up for grabs this November.

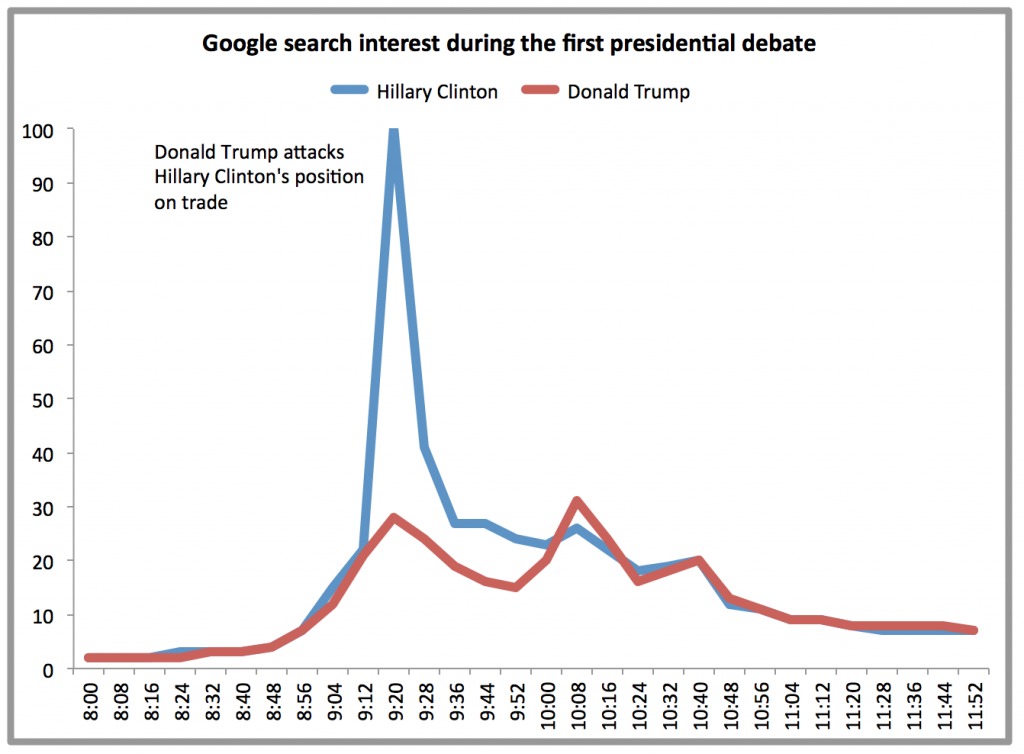

Here’s one indicator of how attuned Americans are right now to the issue of trade, and in particular Clinton’s views on it. The chart below shows Google search interest in the United States over the course of the debate for “Hillary Clinton” or “Donald Trump.” That big spike in searches that included the Democratic leader’s name coincided with Trump’s attack on her flip flop on trade. It was, by far, the moment during the debate when Americans were most interested in either candidates’ position on any issue.

To the extent that Google reflects what people are thinking about, the timing of the spike suggests Clinton has a perception problem around trade.

The thing is, it’s not like Clinton couldn’t take a pro-free trade stance in this campaign and defend America’s traditional role as champion of economic openness around the world. After all, poll after poll has shown a slight majority of Americans actually favour globalization and free trade.

So how might Clinton theoretically battle Trump’s anti-trade rhetoric?

She could start by pointing out how damaging his policies would be to the American economy. Trump has promised to effectively ban American companies from moving jobs offshore, either by levelling punitive taxes against them or through other means—earlier this year he said he would “get Apple to start building their damn computers and things in this country, instead of in other countries.” Part of that plan involves massive tariffs on imports from China, and presumably other low-wage exporting nations. Never mind that this would throw the global economy, including the U.S., into extreme uncertainty, with the potential for another credit crunch as international financial markets figure out how to unwind their sprawling operations. Rising tariffs would also have the devastating effect of driving up costs for the goods and services that America imports, like those iPhones. Consumers in particular have benefited greatly from decades of tariff reductions, which have helped bring down prices, but also introduced greater competition to the domestic market, compelling companies at home to become more innovative and efficient.

Clinton could also point out that trade deals like NAFTA have actually created more jobs than they’ve destroyed—according to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, NAFTA is responsible for adding five million American jobs since its introduction.

Lastly, Clinton could make the case that the attacks on trade by Trump, as well as those within her own party, are misguided. Technological change shares as much, if not more, of the blame for displacing jobs. The problem in both cases is that American policies have failed to help those workers affected by trade and technology to adapt to the changing workforce.

Now try arguing all of that in a debate against Donald Trump, in America, in 2016.

The fact is, at the best of times it’s hard to rally voters by arguing the complex benefits of free trade. Most find it far easier to believe the negative and simplistic rhetoric of “free trade kills jobs.” What’s more, if Clinton took even a moderately more pro-trade stance she would lose support among the large cohort of protectionists within her party. As such she is caught in the mushy, flippy-floppy middle on the issue of trade, leaving a void for Trump to fill with his anger and lies.

It’s too bad, because with the World Trade Organization having just slashed its forecast for international trade growth this year from 2.8 per cent to 1.7 per cent—the slowest annual pace since the financial crisis—and opponents of globalization on the rise everywhere, the struggling world economy could use a champion of free trade right now. That used to be America’s role. Maybe it can be again after this campaign is over, depending on who wins.