Why it’s not enough to simply restore the long-form census

Bringing back the long-form census was the easy part. If this government is serious about data, there is a lot more it should do.

Share

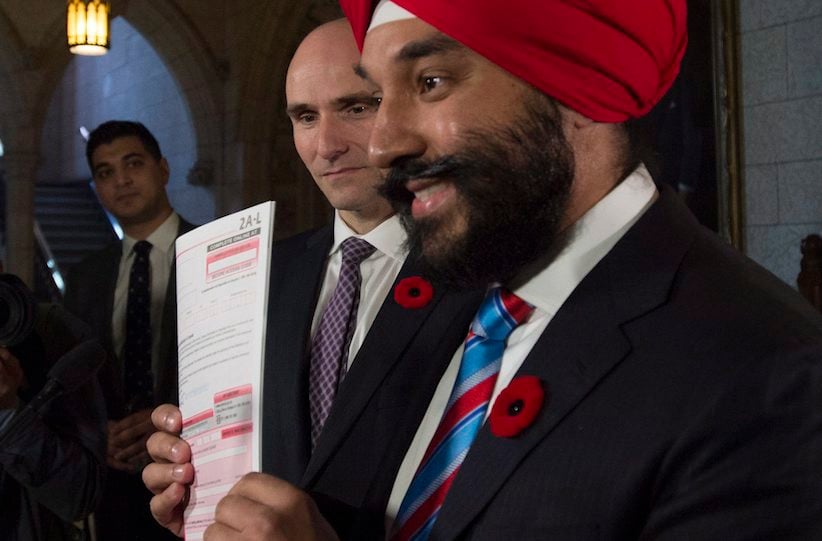

The new Trudeau government has restored the long-form census as one of its first moves. Ministers Jean-Yves Duclos and Navdeep Bains made the announcement on Thursday morning in Ottawa, but provided little actual detail. I think restoring the mandatory nature of the census is a good start, but it is not sufficient—more work needs to be done before we have a census that’s ready for the 21st century.

Before addressing the future, it’s worth recalling why the census generated such passion in some quarters. The previous government and its supporters often used the cancellation of the long-form census as the prototypical example of an issue mattering only to people in the ivory towers of academia or other “Laurentian elites.” If you want a thoroughly technical and nerdy academic answer to why the census matters, you can read my article with UBC colleague David Green here, or watch a more accessible video version put together by Tammy Schirle here. But the census really affected many Canadians outside the leafy quadrangles of academia, too.

On Twitter I interacted with an official from the University of Saskatchewan college of nursing who was trying to plan outreach to Aboriginal communities. Statistics Canada suppressed 2011 National Household Survey (NHS) information for almost half of Saskatchewan communities because of low data quality, meaning she couldn’t figure out the education and Aboriginal demographic profiles of the communities she was trying to serve. Helping bring nursing services—and nursing career opportunities—to historically disadvantaged Aboriginal communities does not strike me as an elite thing. The census matters.

But how exactly should we go about repairing the damage? Census questionnaires need to be thoroughly tested, and then they must be printed. You can’t do this in a few months. According to the Huffington Post, for 2016 the government will use the already-tested questionnaire for the planned 2016 National Household Survey and simply make its completion mandatory rather than voluntary. While 33 per cent of Canadians were requested to fill in the 2011 NHS, apparently only 25 per cent will be asked in 2016. Still, if compliance rates go back to 2006 levels, this should yield a larger number of completed surveys. But much more importantly, the sample should be much cleaner because we won’t have the skewed non-completion problems that plagued the 2011 NHS.

This strategy strikes me as sensible battlefield medicine. Time is short, so the government is constrained in what can be achieved in the few short weeks before sending the census forms to the printer. Making the 2016 NHS mandatory solves the largest problem we had with the 2011 NHS. However, I hope this is just the beginning of a new conversation on the census—and data in general—rather than a one-off restoration of past practices.

In the United Kingdom in 2010, the newly elected Conservative government also had some concerns about their census. But, instead of acting impetuously, they put in place a process to rethink how governments ought to be collecting data in the 21st century. The initial report of this process came out in 2014, and a new “Census Transformation Programme” is at work on plans for the 2021 U.K. Census.

What should Canada do next? Well, the main recommendations of that 2014 U.K. report were to make greater use of existing data already being collected for administrative purposes and greater use of Internet-based census forms. Canada was already doing both those things in 2006. I believe there is room for much more innovation.

I gave a guest lecture a year ago to a meeting of data librarians outlining my thoughts on the future of data in the social sciences, the notes from which can be found here. I remarked that we have more and more administrative data, such as tax, Employment Insurance and immigration records, at the same time as surveys (like the census) are becoming harder to conduct. If we move to greater use of administrative data, we need to be sure we properly balance privacy concerns, researcher access, cost, and data accuracy.

Restoring the mandatory basis for the 2016 survey was necessary, but also easy. The true test of the resolve of the new government on data will come in the actions they take as we begin to plan the 2021 census.