Why the TPP is such a big—and good—deal for Canada

Yes, there will be costs. But on average, we can expect TPP trade liberalization to deliver higher productivity, higher GDP, and higher incomes to Canadians

(Shutterstock)

Share

On October 4th, 1987 negotiators completed the Canada-US Free Trade Agreement. Exactly 28 years plus a day later, 12 countries agreed to form the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP for short). This is a big deal. The TPP will include Australia, Brunei, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, United States, and Vietnam. Together, they account for about 40 per cent of global GDP and over 800 million people. The 12 countries are projected to grow even larger and account for 50 per cent of global GDP by 2050. It’s no exaggeration to call this the largest free trade deal in the world.

So, what’s in the TPP? As there are way (way) too many aspects of the deal to cover in one post, I’ll try to summarize the key changes that may find their way into the current election campaign. For interested readers, though, a technical summary is available here.

What the TPP won’t do

Let me start by saying what is not part of the TPP. There will no doubt be many misleading claims over the coming weeks about this deal, and it is useful to head them off right from the start.

It won’t lead to the privatization of crown corporations like Canada Post or Via Rail. It won’t undermine the ability of the Canadian government to subsidize Canadian cultural industries. In fact, the CBC and Telefilm Canada are specifically exempt from the provisions governing State-Owned Enterprises.

The TPP also won’t constrain governments from tackling environmental challenges. This point deserves more attention. Naomi Klein recently claims that TPP will limit the ability of countries to take action on climate change. This is just silly. Carbon taxes are in no way a violation of anything in the TPP deal. Similar charges are levelled against NAFTA, overlooking the fact that B.C. has a carbon tax which doesn’t violate anything. B.C.’s approach is perhaps the world’s best example of good environmental policy that we should all think carefully about—and one that (hopefully) Alberta will adopt very soon (though again, a topic for another day). TPP does nothing to prevent this.

Related: Maclean’s in-depth primer on the TPP, one of many election issues

Finally, one will also no doubt hear that TPP will increase drug costs. This is false, but there was indeed the potential that this could have been true. One of the main sticking points, primarily between Australia and the United States, was the length of monopoly status afforded to prescription drug companies when they bring out a new drug. For a drug to receive government approval, it must submit a large quantity of data. This data is useful to competitors, such as generic drug companies, when they produce competing drugs. So-called “data protection periods” prevent these competitors from using the original data. (A great Bookings Institute backgrounder on Prescription Drugs and the TPP is here.)

In the United States, this period is 12 years. In Canada, it is 8. In Australia, it is only 5. The US wanted longer periods, while most other countries wanted shorter. The longer the period, the longer the monopoly status of the original drug manufacturer, the longer the drug’s price remains high, and so on. There are some who label the exclusivity periods the “Death Sentence Clause.” That is a little over the top, but it would have certainly increased healthcare costs.

What does TPP do? The countries agreed on a five-year period, as Australia was demanding. As Canada already has a longer period than this, the TPP doesn’t change much at all from our perspective.

What the TPP will do: Lower trade barriers

Let’s get to the heart of the deal: trade liberalization. The TPP will lower tariffs as well as lower non-tariff technical barriers almost across the board. There are far (far) too many changes to list. There are roughly 18,000 tariff lines in the United States that will change for TPP countries. Canada has even more, with about 19,500 tariff lines. (A user-friendly download facility through the WTO is available here.) In time, almost all tariffs on goods and services going in and out of these 12 countries will fall to zero.

Consumers are the big winners here. All too often we focus on lower tariffs for Canadian producers when they export abroad. But we must not forget that lower import tariffs mean lower prices for all of us on the goods and services that we buy. Lower prices means our incomes can go further and our standards of living increase.

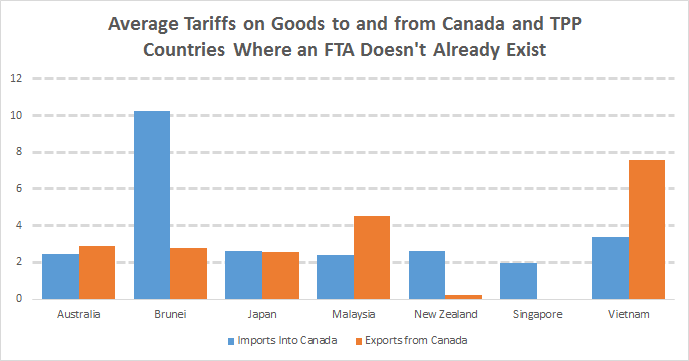

How large are the tariff changes likely to be? There is huge variation across products, but in the graph below I plot the simple average tariff rates for TPP countries that we don’t already have a trade agreement with.

For the most part, tariffs are not that high (a huge success of the WTO, and its predecessor the GATT). Two big countries in the TPP group include Malaysia and Vietnam. Overall, it looks like their tariffs on our goods will fall by more than our tariffs on theirs. For Singapore and New Zealand, the reverse is true (both countries are famous free trading nations).

Of course, tariffs are much higher on many specific goods. Tariff on metals and mineral products imports into Vietnam and Malaysia are roughly 40 to 50 per cent. They will be eliminated in 10 years. Petroleum products have a 30 per cent tariff in Vietnam—also scheduled to be eliminated over 10 years. Aircraft engine parts face a 5 per cent tariff in Australia, which will be eliminated once the deal is in force. The list goes on and on. Instead of listing them here, interested readers can see a (very) long list on the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade, and Development website here, or another summary here.

Some non-tariff barriers will also be falling. The most prominent, and one that will feature loudly across various Southern Ontario ridings this election, is the increased access to imported auto parts for Canada’s auto sector. Currently, to receive preferential treatment under NAFTA, motor vehicles must contain no less than 62.5 per cent of their value from within North America. That is, most of the parts can’t come from Europe, Asia, or elsewhere. Under TPP, the threshold will be for autos to have no less than 45 per cent TPP-originating content.

Will this hurt Canada’s auto sector? Some argue it will, while others are more optimistic. In a previous article I argued that this may actually benefit Canada’s auto sector as a whole. With cheaper parts, assembly operations will become more profitable. Their productivity may rise, as will their employment and exports. If you work at a Toyota plant, this is likely good news. Of course, only time will tell, but it is certainly not obvious that lowering the new Rules-of-Origin thresholds is a “concession” or something detrimental to the Canadian auto sector as a whole.

There are also measures to liberalize services (such as banking) and provisions covering the movement of workers. As services accounts for three-quarters of Canada’s GDP and employs the vast majority of Canadian workers, this is potentially big deal. There’s also much room for growth, with services currently only 17 per cent of Canada’s total trade. As for worker mobility, this will allow technicians or other professionals to easily access these Pacific Rim markets. The details are substantially more complicated here, so I’ll leave those for someone far more knowledgeable to discuss.

The winners and losers (broadly speaking)

So what will be the likely effect of these lower trade costs? On average, we can expect higher productivity, higher GDP, and higher incomes. Of course, there will be costs on some that should not be overlooked.

At the press conference announcing the deal, International Trade Minister Ed Fast said that “we do not anticipate that there will be job losses” though some sectors “will have to adapt.” That’s just silly. There will be job losses in some sectors, and job gains in others. Overall, there will be very little if any change in total employment due to the TPP. Economists don’t focus on the number of jobs, what is far more important (in the long-run) is the type of jobs. Shifting employment towards sectors where we have a comparative advantage will increase our economy’s productivity in the long-run.

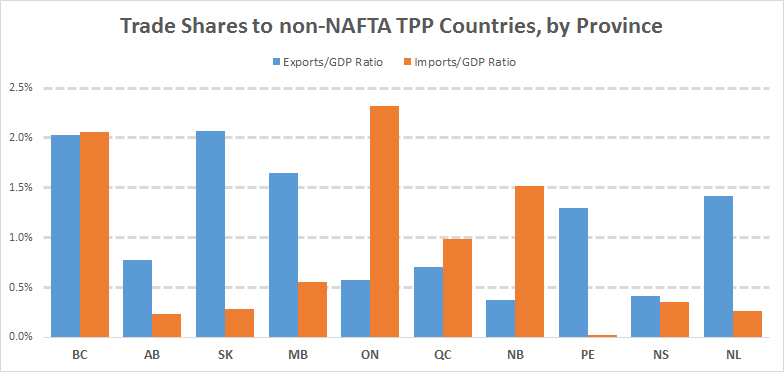

How will each of Canada’s provinces be affected? Below I plot the share of overall economic activity associated with trade with non-NAFTA TPP countries for each of Canada’s provinces.

Typically, these shares are not very large. Approximately exports from BC are 2 per cent of B.C.’s economy; they have a similar share on the import side. Ontario is a big outlier here, with imports equivalent to nearly 2.5 per cent of its GDP compared to only 0.5 per cent involved in exports. Ontario consumers and businesses that import inputs from abroad are going to win. About one-third of Ontario imports from these countries are in the form of equipment (HS codes 84 and 85, for those interested). Business importing such equipment will face lower costs, and therefore improved competitiveness. Also, Ontario consumers spend over $1 billion in food imports from non-NAFTA TPP countries. Our eventually lower tariffs will be a big boost to their pocketbooks.

Of course, only with time and further detailed reflection and analysis will we know the true consequences of this deal. From my perspective (for what what’s worth), it will be good for Canada’s economy overall. Of course there will be difficult adjustments for some workers in Canada, but our focus and attention should be on designing policies to help those adversely affected, not in blocking the deal outright as some propose.

Supply management and the TPP

Let me end with what might be the most contentious issue for the election: increased imports of dairy, chicken, turkey, and other “supply managed” products. The NDP has, and will likely continue, to demand Canada “protect” its dairy farmers with high tariffs and quotas on production. So, how does TPP affect dairy farmers and the broader Supply Management system? It barely changes a thing. The system as a whole will be retained.

There will be modest changes, however, with slight increases in the amount of certain agricultural good allowed into Canada tariff-free. These quota increases are fairly minor: equivalent to 3.25 per cent of the Canadian market for dairy, 2.3 per cent for eggs, 2.1 per cent for chicken, 2 per cent for turkey, and so on. This benefits Canadian consumers, unambiguously. What about producers? Increased competition will be a challenge, for sure, but the government will provide compensation. Affected farmers will have 100 per cent income protection for a full 10 years after TPP comes into force. The government is also setting aside $1.5 billion to compensate for lost value of quotas. Some estimate this package of compensation to be worth close to $4.3 billion over the next 15 years.

What do other countries think about this? Accounting for close to one-third of international dairy trade, New Zealand stood to gain the most from liberalization. It is surely disappointed. The trade minister there points out that, on balance, he’s happy as TPP “establishes in the long run, complete elimination of all tariffs on everything that New Zealand exports,” with two exceptions: (1) beef imported into Japan, and (2) some dairy products into Canada. He points out though that the work is not over. The deal will open up “political space for future generations” to build on. He also wisely notes “the excellent is almost always the enemy of the good”, and is happy where things landed.

We shouldn’t forget, though, that supply management is a terrible policy, especially for low income Canadians. Although TPP does little to change it, we can eliminate it unilaterally—we don’t need a trade deal to do it. In time, hopefully, better policy will prevail.

Trevor Tombe is an assistant professor in the department of economics at the University of Calgary. Follow him on Twitter: @trevortombe